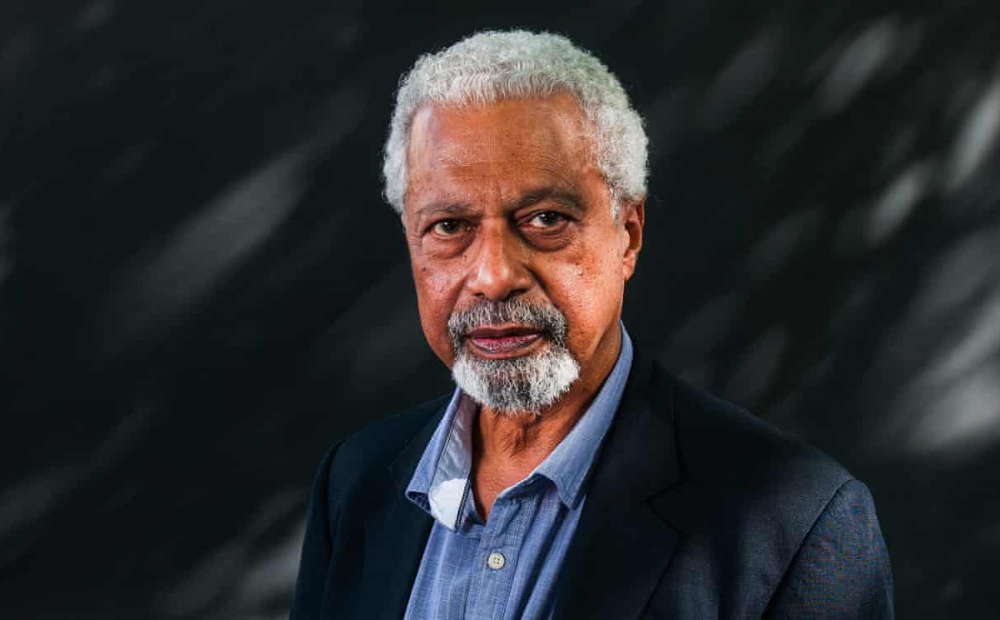

‘The theme of the refugee’s disruption run throughout his work’ … Abdulrazak Gurnah. Photograph: Simone Padovani/Awakening/Getty Images

The Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded on Thursday to Abdulrazak Gurnah for “his uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism and the fate of the refugee in the gulf between cultures and continents.”

Gurnah was born in Zanzibar, which is now part of Tanzania, in 1948, but he currently lives in Britain. He left Zanzibar at age 18 as a refugee after a violent 1964 uprising in which soldiers overthrew the country’s government. He is the first African to win the award — considered the most prestigious in world literature — in more than a decade.

He is preceded by Wole Soyinka of Nigeria in 1986, Naguib Mahfouz of Egypt, who won in 1988; and the South African winners Nadine Gordimer in 1991 and John Maxwell Coetzee in 2003. The British-Zimbabwean novelist Doris Lessing won in 2007.

Gurnah’s 10 novels include “Memory of Departure,” “Pilgrims Way” and “Dottie,” which all deal with the immigrant experience in Britain; “Paradise,” shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 1994, about a boy in an East African country scarred by colonialism; and “Admiring Silence,” about a young man who leaves Zanzibar for England, where he marries and becomes a teacher. His most recent work, “Afterlives,” explores the generational effects of German colonialism in Tanzania, and how it divided communities.

Gurnah’s first language is Swahili, but he adopted English as his literary language, with his prose often inflected with traces of Swahili, Arabic and German.

Anders Olsson, the chair of the committee that awards the prize, said at the news conference on Thursday that Gurnah “is widely recognized as one of the world’s more pre-eminent post-colonial writers.” Gurnah “has consistently and with great compassion, penetrated the effects of colonialism in East Africa and its effects on the lives of uprooted and migrating individuals,” he added.

The characters in his novels, Olsson said, “find themselves in the gulf between cultures and continents, between the life left behind and the life to come, confronting racism and prejudice, but also compelling themselves to silence the truth or reinventing biography to avoid conflict with reality.”

In an interview with The New York Times on Thursday, Gurnah said he was making a cup of tea when he got the call from the Nobel committee early in the morning. “I’m still absorbing it,” he said.

He described how he “stumbled into writing,” partly as a way to cope with his sense of dislocation as a young refugee in England. “The thing that motivated the whole experience of writing for me was this idea of losing your place in the world,” he said. “Misery, poverty, homesickness, those kinds of things, you start to think hard and reflect on things.”

Gurnah began by writing recollections of his homeland and other snippets without ever intending to publish them, but over the years, stories started to take shape. What began as private reflections later struck him as part of a larger, more universal story, about “the way in which colonialism transformed everything in the world, and people who are living through it are still processing that experience and some of its wounds,” he said.

The same themes that occupied him early in his career, when he was processing the effects of his own displacement, feel equally urgent today, he said, as both Europe and America have been gripped with a backlash against immigrants and refugees, and political instability and war have driven more people from their home countries. “It’s a kind of meanness and miserliness on the part of these prosperous countries that say, we don’t want these people,” he said. “They’re getting these literally handfuls of people compared to European migrations.”

The news of his Nobel was celebrated by fellow novelists and academics who say that his work deserves a wider audience.

The novelist Maaza Mengiste described Gurnah’s prose as being “like a gentle blade slowly moving in.” “His sentences are deceptively soft, but the cumulative force for me felt like a sledgehammer,” she said.

“He has written work that is absolutely unflinching and yet at the same time completely compassionate and full of heart for people of East Africa,” she said. “He is writing stories that are often quiet stories of people who aren’t heard, but there’s an insistence there that we listen.”

Laura Winters, writing in The New York Times in 1996, called “Paradise” “a shimmering, oblique coming-of-age fable,” adding that “Admiring Silence” was a work that “skillfully depicts the agony of a man caught between two cultures, each of which would disown him for his links to the other.” But despite being hailed as “one of Africa’s greatest living writers” by the scholar Giles Foden, Gurnah’s books have rarely received the kind of commercial reception that some previous laureates have.

In the prelude to this year’s award, the literature prize was called out for lacking diversity among its winners. The journalist Greta Thurfjell, writing in Dagens Nyheter, a Swedish newspaper, noted that 95 of the 117 past Nobel laureates were from Europe or North America, and that only 16 winners had been women. “Can it really continue like that?” she asked.

Who else has recently won the prize?

The American poet Louise Glück was awarded last year’s literature prize for writing “that with austere beauty makes individual existence universal,” according to the citation from the Nobel committee. Her award was seen as a much-needed reset for the prize after several years of scandal.

In 2018, the academy postponed the prize after the husband of an academy member was accused of sexual misconduct and of leaking candidates’ names to bookmakers. The academy member’s husband, Jean-Claude Arnault, was later sentenced to two years in prison for rape.

The following year, the academy awarded the delayed 2018 prize to Olga Tokarczuk, an experimental Polish novelist. But the academy came in for criticism for giving the 2019 prize to Peter Handke, an Austrian author and playwright who has been accused of genocide denial for questioning events during the Balkan Wars of the 1990s — including the Srebrenica massacre, in which about 8,000 Muslim men and boys were murdered.

Lawmakers in Albania, Bosnia and Kosovo denounced the decision, as did several high-profile novelists, including Jennifer Egan and Hari Kunzru.

Who else won a Nobel Prize this year?

-

David Julius and Ardem Patapoutian were awarded the prize in physiology or medicine on Monday for their discoveries about how people sense heat, cold, touch and their own bodily movements.

-

Three scientists whose work “laid the foundation of our knowledge of the Earth’s climate and how humanity influences it” were awarded the prize for physics on Tuesday: Syukuro Manabe of Princeton University; Klaus Hasselmann of the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology in Hamburg, Germany; and Giorgio Parisi of the Sapienza University of Rome

-

Benjamin List and David W.C. MacMillan were awarded the chemistry prize on Wednesday for developing a more environmentally friendly tool to build molecules.

When will the other Nobel Prizes be announced?

-

The Nobel Peace Prize will be announced on Friday in Oslo. Last year, the award went to the World Food Program.

-

The Nobel in economic science will be announced in Stockholm on Oct. 11. Last year’s prize was shared by Paul R. Milgrom and Robert B. Wilson, the inventors of new auction formats which have been used by governments to allocate scarce resources.