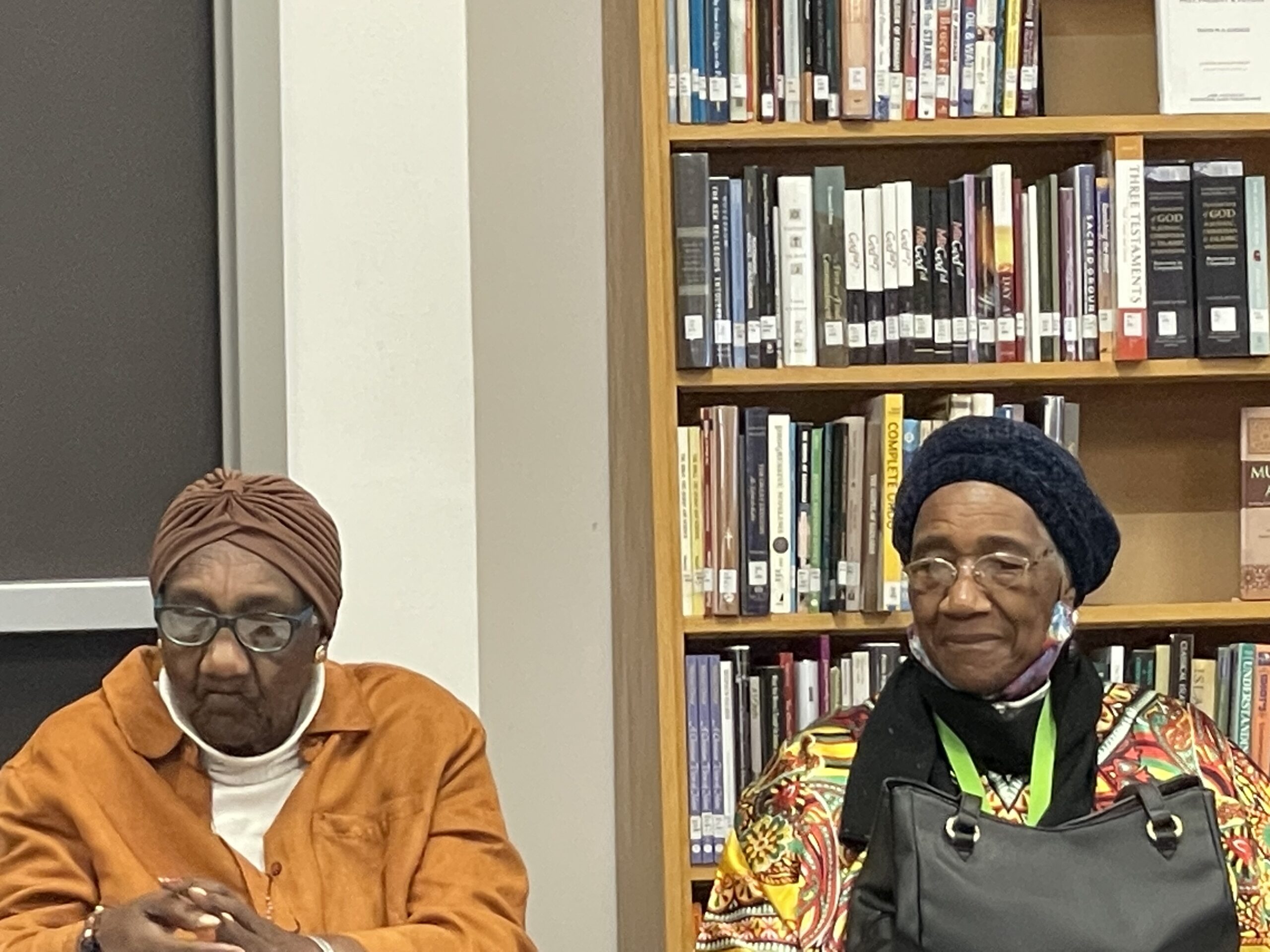

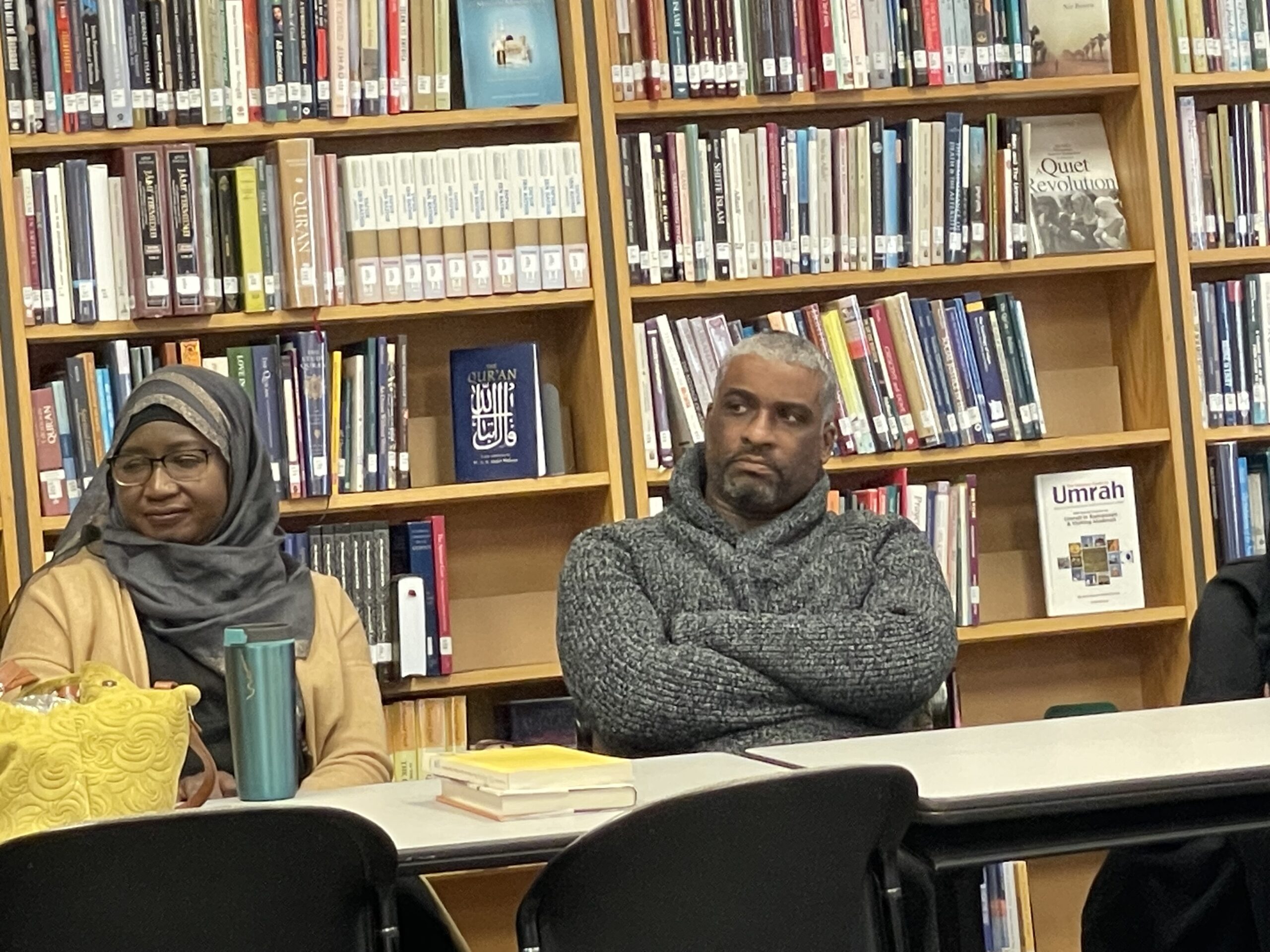

The Black Muslim Experience panelists: (from left to right) Imam Bramouse Fahad Muhammad of Masjid Sultan Muhammad; Burhan Clark, Milwaukee Islamic Dawah Center board chairperson; Sumaiyah Clark, enterprise project administrator for the Milwaukee County Department of Health and Human Services; and Basimah Abdullah, principal at the Clara Mohammed School.

“My first experience of racism was in the masjid,” Sumaiyah Clark of Milwaukee recalled. Clark, whose grandparents were among the first Muslim families in Milwaukee, shared an incident that happened when she was 6 years old. “I was so excited because for Eid I got the Superstar Christie Barbie (the first Barbie with the facial features of a Black woman). She was brown. She had this glorious hair and a sparkly dress. I go to the masjid and the other girls are like, ‘Oh my God, she’s so ugly!’

Her brother Burhan Clark, Milwaukee Islamic Dawah Center board chairperson, said, “When I was young, there were two types of Muslims. Either you were with the Nation or you were a terrorist. Being a Muslim who’s not part of the Nation and not a terrorist, I felt I had to educate people about who I am, what Islam is and work through their automatic assumptions.”

The Clarks were among a panel of four distinguished participants discussing “The Black Muslim Experience.” The event, co-sponsored by the Milwaukee Muslim Women’s Coalition and the Milwaukee Islamic Dawah Center, was held in February at the Islamic Resource Center in Greenfield and organized by IRC librarian Muna Jaber. Jaber also created a book display featuring books on Black Muslim history and Islam that are available to the public for checkout from the IRC, the largest Muslim lending library in Wisconsin.

MMWC board member Fatoumata Ceesay welcomed the audience to hear from the panel of African American Muslims in the diaspora as they shared their experiences of being Black and Muslim, including what they wish others knew and how others can best support them.

Panel members were Sumaiyah Clark, the Milwaukee County Department of Health and Human Services enterprise project administrator; Burhan Clark, Milwaukee Islamic Dawah Center board chairperson and owner/operator of Heart 2 Heart, a basic medical training company in Milwaukee; Bramouse Fahad Muhammad, imam of Masjid Sultan Muhammad and director of education at Clara Mohammed School in Milwaukee; and Basimah Abdullah, Clara Mohammed School’s principal.

See the full panel discussion here.

This article features paraphrased highlights of the discussion.

How do the struggles you deal with in the Milwaukee community compare to the struggles you face within the Muslim community?

The panelists agreed that they face challenges both as Muslims and as African Americans, including prejudice and discrimination from Muslims and non-Muslims alike. They are impacted both as individuals and as Black Muslim-led organizations.

Burhan Clark: Other Muslims had a set of assumptions about me. They’d ask, ‘So, when did you become Muslim? Did you become a Muslim in jail?’ They’d assume my family is Christian and ask, ‘What challenges do you face with your family?’ I got used to having to explain. It was sometimes fatiguing. I felt a sense of independence, that I needed to define my faith rather than depending on other people to define Islam as a group.

Basimah Abdullah: Exactly! I was 18 when my mother converted through the Nation of Islam, and she converted all of us. When she converted, it wasn’t even a question (if she’d raise her children to be Muslims) because my mother had been searching for my whole life. I have been baptized in just about every revival tent down the California coastline. We knew the Bible in and out. But when my mother because Muslim, that was the first time I ever saw her with peace.

So, I get it both ways. I’ve had people say, ‘Oh, you look Muslim. You dress like people in my country.’ And I’d say, ‘Yeah, I’m Muslim.’ Muslims didn’t believe me. They ask if I know about Prophet Muhammad (pbuh).

(Non-Muslims) would say, ‘You seem like an intelligent young woman. Why are you in that religion?’

‘Because I am an intelligent woman,’ I’d answer.

We don’t want to be isolated. At the Clara Mohammad School, we always try to keep the school within the community. Our children need to be able to deal with anybody and everybody. That’s why I always get involved in organizations in the community.

Still, we have difficulty being accepted. Milwaukee’s Clara Mohammad School is in its 50th year and still we have difficulties with contractors and with getting loans from banks. Banks notice that we pay our bills and stay in good standing, but then they disappear.

Burhan Clark: At the Dawah Center, a big challenge we face is the retention of good staff. For the African American community, people are always looking to move. If you are Black and you are from Milwaukee, you’re thinking about getting out of here and going somewhere else. This is a consistent thing among our educated young men and women who have good skills.

Sumaiyah Clark: Unfortunately, the same experiences that happen in the general Milwaukee community also happen in the Muslim community. I have two children and I am very mindful about choosing not to send them to an Islamic high school because I do not want them to face the same racism I experienced growing up in this community. As a parent, I’ve had to consider the extreme racism that unfortunately perpetuates the Muslim community here.

In Milwaukee, we also suffer from structural racism. We know that on average, black people here die 14 years earlier than their white counterparts. There’s something systemic driving that.

And going back to my grandparents, in the forties and fifties, there was a time of urban renewal. Now Highway 43 occupies the space where it was happening.

Immigrant families moved in the city and more came in the seventies and eighties. They were able to move to the south and the suburbs and buy homes. My family wasn’t able to do that because of redlining. We couldn’t even move to Wauwatosa until the 1980s. I wish I could say things were very different at the masjid. Unfortunately, that has not been the case.

Imam Bramouse Fahad Muhammad from Masjid Sultan Muhammad said he sees the same segregation in Milwaukee’s Muslim community as he does in Greater Milwaukee.

Imam Muhammad: We all lived through and have experienced racism and systemic racism, and other forms of oppression. Regardless of all that, we decided we were going to do something on our own, for ourselves. We have built various masjids serving diverse communities.

As a student of the history of Islam in America, I want us to understand that although there are pockets of Muslims in other states across America, there are three cities where Islam took a foothold and has made an important imprint in America—Detroit, Chicago and Milwaukee. We are establishing our own lives, our own discipline, our own religion, our own business endeavors and our own homes. We did that during segregation.

What I see now is that we Muslim African Americans have weakened in that passion, on that sense of urgency since integration. Before we had no choice but to stick together. Once integration happened, we said, ‘I’m going to cross the bridge.’ it weakened us socially, economically and politically.

However, Milwaukee is still one of, if not the most, segregated cities in the United States. And on a large scale, our Muslim community is also highly segregated. That’s the elephant in the room.

What could others do to better support you?

Imam Muhammad: I believe the big charge is not so much what others could do for us but what we could do for ourselves. We are not looking for handouts. I want to be very clear about that. Don’t be like the father who doesn’t spend time with his child and just gives a hundred dollars and says, ‘Son, see you next year.’

Though we are not the most wealthy people and sometimes we are small in numbers, we have integrity and dignity. What I’d like to see others do is work collaboratively with us and work with our Clare Mohammad School. Come socialize, visit, and establish connections with us.

Among ourselves, we Muslims who are African Americans went through things that weakened our bonds in the past two or three decades. We have some unresolved issues. We need to try to rebuild those bonds.

Sometimes Muslims have a tendency to say who is and is not Muslim. That’s not your job. You just be the best believer you can be. If we’re people of faith, then let’s demonstrate that faith in our love, in our brotherhood to each other and for each other.

Burhan Clark: We talk about systemic racism but I think all racism is interpersonal. That’s the root. It’s easy to say, ‘The system is racist; not me.’ But that’s not true. It comes from the way we talk about other people at the dinner table.

If you have heard people talk about Palestine, you may have heard them say, ‘These people are thugs. Look at their criminality, etc.’ But if you know someone in Palestine, you would look at their situation. You’d say, ‘Look what these people have been through. Look at the oppression they are under, look at the lack of resources in their communities. The only reason you were calling them names is because you didn’t really know their situation.

It’s similar when someone comes here and buys a store. They look out at the African Americans and say, ‘Look at these thugs.’ Even among African Americans, we talk about ‘those people over there.’ Why aren’t we looking at the situation holistically?

Even when donating, sometimes there is a feeling of superiority as opposed to a sense of sharing and uplifting each other. We need to minimize the distances we are feeling. We need to socialize our children and ourselves to see our shared humanity.

As Muslims, we are supposed to be close to each other. We think it’s going to work out, but as long as we don’t talk about racism, it won’t. You have to actively teach, develop and nurture the attitudes you want to see. This is a job for all of us. We have to understand there’s not some superiority of someone’s culture.

I’m glad we are having discussions like this one. We need to talk about this issue consistently, not just during Black History Month.

Imam Muhammad: Concerning African Americans or black people, we were completely robbed of our history. Many of us don’t even know who our grandparents or great-grandparents were. And we certainly don’t know the languages we spoke. This is something that we all know. When Islam came to us, we saw ourselves as a completely new people. We had no connections to the African continent. That all came later. What we saw was what God wanted us to come to, to be a righteous Muslim.

Sumaiyah Clark: My grandmother is 94 and she talks about when she was 5 years old in Mississippi. Women would go into the field at the crack of dawn and go through the prayer motions. She talks about that and about how they had to hide it. We are still trying to rid ourselves of that internalized oppression because of the external oppression we experienced.

What can other Muslims do to best support Black Muslims? I would like you to ask yourself if you are participating in the oppression of Blacks when you open a store? Where do we see concentrations of crime? Where do we see concentrations of violence? It’s around liquor stores.

We know that a majority of liquor stores and other predatory businesses are run by Muslims. You have the responsibility to tell people that is unacceptable.

Also, as Muslims, we sometimes say something is forbidden because of cultural bias. My son has locks and some people have told me they are haram (forbidden). How can they be? We have to be mindful of how we are getting our interpretations of Islam and how those interpretations are influenced by caste-based systems, colonialism and tribalism. Islam came to get rid of those things.

What makes you proud to be Black and Muslim or Muslim period?

Basimah Abdullah: Do you know what we had to go through to become Muslim in this country? That’s to be proud of. We feel the racism within the Muslim community. I mean there’s no pussyfooting around on that one. But we are also dealing with, ‘You’re not a real Muslim because you didn’t come from a Muslim country’ or ‘You don’t really understand the religion because you don’t know the language.’

What we have to do is have the heart of a believer to want to know. Allah is blessing us anyway.

Imam Muhammad: What personally makes me proud to be a Muslim is what I read about the people who have been through the experience. It is truly humbling. I am proud of how Allah has blessed the African American community for our sincerity.

Burhan Clark: Our Islam was the most important thing to us. I’m proud of how we are able to respond to things in America. I remember meeting a brother who said, ‘I just can’t fast when I’m in America. There’s food everywhere.’ In contrast, I feel like I’m in a rich environment where I have a lot of things I can work with. There are a lot of things I can try to help with.

When I talked earlier about a lot of people wanting to leave versus being in a place that may have more problems, I feel sort of proud, proud to be in a position where there are problems I can help with. What else am I here for? It’s an opportunity to have an impact on society.

Sumaiyah Clark: I’m very proud of what this room represents—we have a very diverse community, with many ways to practice and worship. Just being part of this global group seeking to be closer to Allah. I’m grateful Allah chose us to be Muslims.

Burhan Clark: We can ask for reparations, and I’m not saying we shouldn’t get them, but what kind of reparations could white America give us that’s better than what we have with Allah?

Clark related the experience of Bilal, an Abyssinian who was a slave in Mecca, and became the first man to call Muslims to prayer. Bilal’s master abused him, making him lie on burning sand, having large slabs of rock placed on his chest, and other tortures, because he refused to deny Islam, his new faith. A wealthy merchant, Abu Bakr, heard of his plight.

When Bilal was being oppressed, Abu Bakr paid for his freedom. Bilal had to ask the question, ‘Are you freeing me now to be your slave?’ But that was not the case. Abu Bakr freed Bilal for the sake of God.

That could have happened to the large group of African Americans. We could have come under somebody else’s rule, but Allah didn’t want that. They survived and received Islam the way they did. It’s mind-boggling. It’s miraculous. It’s very special and important, and I’m very proud of that.