PALESTINIANS EVACUATING AL-BUREIJ REFUGEE CAMP IN CENTRAL GAZA FOR DEIR AL-BALAH AS THEY ARE FORCED TO FLEE SOUTH UNDER ISRAELI BOMBARDMENT AND SHELLING, DECEMBER 22, 2023. (PHOTO: OMAR ASHTAWY /APA IMAGES)

I was born across the street from where Jesus was born on a street called, the Milk Grotto Street, in Bethlehem. My family has deep roots in the little town. We have been Christians for the last fifteen centuries, if not longer. My family name “Raheb” means “monk,” connecting it to the ancient monasteries established in the wilderness around Bethlehem since the fourth century AD. My first name, “Mitri” refers to a Greek-Orthodox saint, St. Demetrious, a fourth-century martyr in the Roman empire. In the second half of the nineteenth century my grandfather, whose name I carry, having been brought up as an orphan in a German Protestant school, decided to leave the Orthodox church and join the Lutheran church in town, so I grew up as a Lutheran.

My earliest childhood memories go back to the year 1967, when Israel occupied our town. I still remember our neighbor running to tell my father that Israeli troops had entered Bethlehem. My mother wanted us to go across the street to seek refuge at the Church of the Nativity. She believed that we would be safe there. My father refused to leave home. He argued that he would not repeat the mistake made in 1948, in the Nakba. He said he would rather die in his home rather than evacuate it and never come back. My mother knew that there was no way to convince my father, so she took me, their only child, and hid in a large room within the compound of the Church of the Nativity with many other Christian families from the neighborhood.

Growing up as a child in Bethlehem was special. For us in Bethlehem, the Patriarch parade on Christmas Eve was very special. To see him greeted by a multitude of scout groups playing their instruments and marching through the narrow streets of Bethlehem, followed by policemen on their giant horses, while the mayor, the city notables, and international tourists were waiting at Manager Square to greet him. As kids we were waiting fervently for Christmas to come, for Santa to visit our Lutheran church bringing us “kiddy kits”; for our parents to buy us new clothes and shoes; for us to enjoy the delicious Christmas chocolate. Very special were the plays that were put together at school where we had to memorize passages from the Christmas story about the holy family, about the shepherds and the magi, and about King Herod and Augustus Caesar. It was a beautiful and uncluttered celebration.

Later in life, during my years of study in Germany, I witnessed how Christmas became more and more commercialized. The festivities there, with large-scale Christmas markets, Christmas carols played in malls, and Christmas trees sold at city squares. In this context, the Christmas story seemed more like a fairy tale, based in a very different climate than the one I know. Indeed, all these new, Northern European elements seemed vaguely alien to someone who knew the original story so well. It was all about Santa, the reindeer, the snow, the jingle bells, and the goodies. I must confess that all of this has its charm. Our children, too, now love Santa.

But Christmas can be hard in Palestine. After twelve wars in my lifetime, we are not always up for all the festivities. At times, we have no choice but to cancel Christmas. Now is such a moment, with the war on Gaza making everyday life so hard for our people. The churches in the Holy Land decided to cancel all Christmas festivities, and so did the city council of Bethlehem. For some children, it is disappointing. They might ask: what is Christmas without the glamour, without the tree, and without the gifts?

These questions are not always easy to answer, but as a theologian, it has given me an opportunity to look at the Christmas story all over again, through a Palestinian lens. Once again, I feel close to the conditions that Bethlehem knew at the time of the Nativity. Indeed, the more I study the similarities, the more deeply I feel the story.

When reading the biblical amount, we hear of a Palestinian Jewish family living under the rule of a distant Roman Emperor, with King Herod as a local administrative subcontractor. We hear of a man called Yosef, who is ordered by an imperial decree to go register in his native town, a Roman way to exploit the subjugated people with taxes. Together with his pregnant fiancée, Mary, he has to move from the North of Palestine to the South, covering more than a hundred miles on foot through a very hilly terrain. When they arrive in Bethlehem, Mary is about to give birth, but where? Hounded by the authorities, with nowhere else to go, she is forced to give birth in a stable.

Yet the story continues. When King Herod hears that a liberator “savior” is born, he becomes worried about his position, and orders his soldiers to kill all newborn babies. To save their lives, the holy family has to flee South, to Egypt, where they stay for two years, then return after the death of King Herod. Jesus was born thus as a refugee. The Christmas story is a highly political story, and a story for our time.

Even the famous Christmas song “Gloria in Excelsis Deo,” sung by the angels, is political. We sing of a glory that belongs to God, not to Caesar. We sing of a just peace, not the Pax Romana, implemented by subjugating other nations, but rather a just peace, offering good tidings for the poor and marginalized.

The biblical Christmas story is thus a Palestinian story par excellence. It is not a fairy tale from the distant past. It is not a story of Northern European elves, flying on sleds pulled by magical reindeer. It is a real story, of a real people, in a real time and place. It is a story that we can profoundly identify with in December 2023.

Hundreds of thousands of Palestinian families have been ordered by the Israeli military to evacuate from the north to the south of the Gaza strip, among them fifty thousand pregnant women. Once again, the shelters are all overcrowded, and there is no room at the inn. As in the time of Herod, many thousands of innocent children were murdered, now through Israeli airstrike.

Since the Oslo Accords of 1993, we have been hearing about a Pax Americana. But the peace process has brought five wars and far more Israeli settlements on Palestinian land. The Christmas story is a reminder that glory belongs not to the mighty but to the Almighty. There is no military solution to the Palestinian issue; only a political one, beginning with an immediate ceasefire. Too many Israelis and many more Palestinians have been killed already. It is time to change course. The real Christmas will come when the Palestinian children and the Israeli children can live in peace side by side with dignity, equality, and prosperity. May this Christmas season give us the courage to work towards that. What better gift can we give the land that gave us Christ and Christmas.

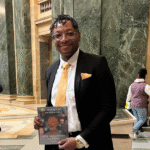

Rev. Prof. Mitri Raheb is the Founder and President of Dar al-Kalima University in Bethlehem. Dr. Raheb holds a Doctorate in Theology from the Philipps University at Marburg, Germany and is the author and editor of over 50 books.