Story at a glance

- In the years following 9/11, anti-Muslim sentiment grew in the United States.

- From 2000 to 2009, hate crimes against Muslims spiked 500 percent.

- Muslim Americans coalesced and in 2020 out of the 1.5 million registered to vote, 71 percent cast a ballot.

The political and cultural power of Muslim Americans has grown in the past 20 years as a result of an expanding voter base and record numbers of candidates running for office at both at the local and national level.

But the rise in political power has come with its difficulties.

Since the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks carried out by Al Qaeda on American soil, Muslims living in the U.S. have experienced political and cultural firsts along with an exponential rise in hate crimes, bullying, harassment and racial profiling.

In the years following 9/11, anti-Muslim sentiment grew in the United States.

Wa’el Alzayat, CEO of Emgage, a Muslim American civic group, explained to Changing America that Muslim Americans could have stayed silent in the aftermath of 9/11 as a “way to defend their interests and their freedoms” because of hostile rhetoric.

But eventually, Alzayat said, the community warmed to a more affirmative agenda, engaging in political discourse and becoming an active voter block in U.S. elections.

By 2020, a record number of Muslim Americans voted and were running for elected office.

Emgage found there were 1.5 million registered Muslim American voters in 2020 and nearly three-quarters — 71 percent — cast a ballot. The figure was four percentage points higher than the national average of about 67 percent.

The country has also seen an increase in the number of Muslim candidates and elected officials.

Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison (D) was the first Muslim elected to Congress in 2007.

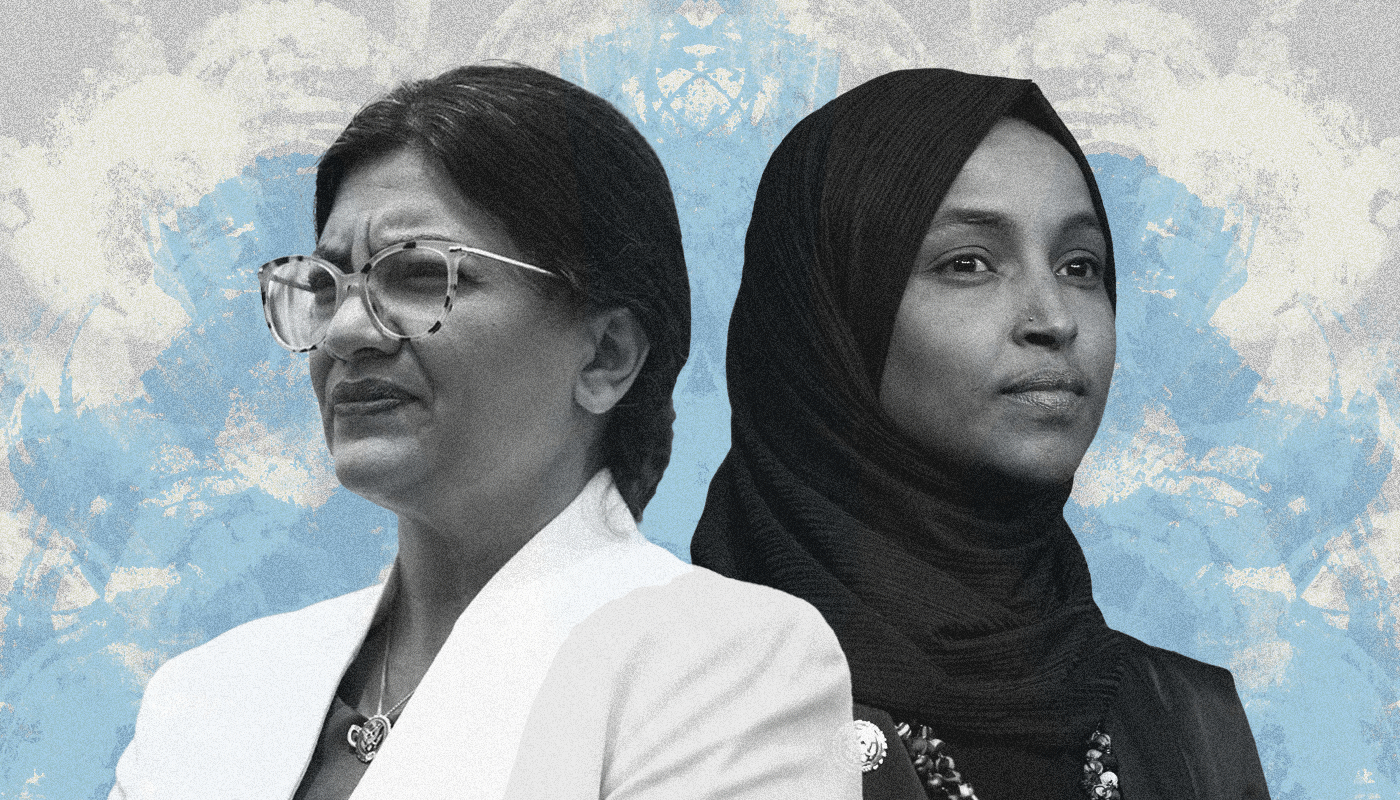

In addition, Reps. Rashida Tlaib (D-Mich.) and Ilhan Omar (D-Minn.) became the first Muslim women to be elected to Congress. The progressive “squad” members are two of the most prominent Muslim voices in American politics, elected in the “blue wave” 2018 midterms during the Trump administration.

A record 81 Muslim American candidates ran for office in 2020 across 28 states and Washington, D.C., according to a report by the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR).

But these milestones have been accompanied by a growing rise in Islamophobic incidents in the U.S.

Data from Brown University revealed that from 2000 to 2009, hate crimes against Muslims spiked 500 percent.

Beyond former President Obama’s presidency, critics contend that former President Trump’s policies exhibited animosity toward the community, such as his travel ban, which included predominately Muslim countries.

In 2020, the Justice Department (DOJ) found there were 110 anti-Muslim incidents in the U.S., the second highest after anti-Jewish acts.

The DOJ also found that religion was the second-most common reason for single-bias incidents in the U.S.

A Pew Research survey found Republicans increasingly associated Muslims and Islam with violence, with 72 percent of Republicans in 2021 believing Islam was more likely than other religions to encourage violence.

Among Democrats, 32 percent felt the same.

Abdullah Hammoud, the first Muslim American mayor of Dearborn, Mich., told Changing America that there was a sense of urgency among members of the Muslim American community to step up and push back against Islamophobia in a post 9/11 America.

Before becoming mayor, Hammoud ran for a seat in Michigan’s state legislature. He shared that doors were “slammed in his face” when he introduced himself.

Hammoud, a Michigan state lawmaker has won the Dearborn mayoral race, making him that city’s first Arab American mayor. (Robin Buckson /Detroit News via AP)

“I knocked on a neighbor, who was a primary Democratic voter, two blocks from my house at the time. And when I said, ‘I’m Abdullah Hammoud and I’m running for office, he replied, ‘I’m disgusted that you’re my neighbor,’ and slammed the door in my face.”

Hammoud told Changing America that one of the first questions his parents asked him when he shared his intentions to run for elected office was if he would run on the name “Abdullah”.

“Many told me I would never win with a name like Abdullah and told me to change my name to Abe Hammoud,” he shared.

Tlaib and Omar have previously shared that they’ve received violent threats during their time in Congress.

During a press conference, Omar played a voicemail she received in which the caller characterized her as a “f—ing Muslim piece of shit” — one hellbent on “taking over our country.”

Omar has also received attacks from congressional colleagues including Rep. Lauren Boebert (R-Colo.), who described her as a member of the “jihad squad” and even suggested she was a “terrorist sympathizer.”

The Minnesota Democrat published a statement last year that called out the Republican party for not holding their members accountable for anti-Muslim hate and harassment.

“This is not about one hateful statement or one politician; it is about a party that has mainstreamed bigotry and hatred. It is time for Republican Leader McCarthy to actually hold his party accountable,” the 2021 statement said.

Hatem al-Bazian, Director of the Islamophobia Research and Documentation Project at University of California, Berkeley said that both Omar and Tlaib experience “constant assault” on their status, personhood and more.

“The attacks are not only from the Republicans but sometimes even from centrists or establishment Democrats, so you can see this in how Islamophobia is the ‘big elephant’ or the ‘big donkey’ in politics and has no party affiliation,” he said.

Attacks on both Omar and Tilab fit into this sense of defining “who is an American” and who’s not, according to al-Bazian.

“It’s constantly trying to delegitimize who they are and in essence their religion and constant demonization because of their religion,” he added.

But despite these challenges, Muslim Americans are not only increasing their presence in politics but also in American pop culture.

Marvel Studios showcased its first Pakistani-American character in its “Ms. Marvel” series while Netflix has featured Palestinian American comedian Mo Amer’s scripted show and Indian American Hasan Minhaj’s stand up specials.

Al-Bazian said that despite representations in cinema and entertainment, they are not a sign prejudice against Muslims has been eradicated.

“For any community to have the space to be able to articulate and narrate stories about themselves is a positive development,” he said. “But if we take inclusion on the screen, and in different settings, as a sign that racism and Islamophobia is at an end, then the Black and Jewish community’s strides in cinema would show that the strong currents of racism still persist.”

He added that there’s still an “avalanche” of negative content out there in both television shows and movies where Muslims are portrayed as terrorists.

Hammoud says that he hopes these “firsts” of Muslim representation are not the last.