The March 18 event was attended by students, alumni, Georgetown community members, Muslim leaders in Washington, DC, a representative of the DC Council and diplomats from Turkey, Qatar and Indonesia.

Every day, Tabshir Forkan (C’24) walks to Georgetown’s masjid, or mosque, on campus for its daily prayer services.

He steps into the sunlit, open worship space to pray. Afterward, he often finds himself in the masjid’s community space, attending spiritual discussions and dinners, studying, meeting with friends.

“It’s a space I feel myself drawn to,” he says. “I can’t seem to stay away.”

In spending time at the masjid, Forkan has felt his Islamic faith deepen — something he had worried about in leaving his Muslim community and masjid back home for a Catholic, Jesuit university, and forging his own identity as a Muslim.

“To come here and not lose that space and not lose that community — only to find a new community and new friends to be around — has been incredibly powerful,” he said. “It has only helped me progress along and connect more with my faith.”

On March 18, Georgetown officially opened the Yarrow Mamout Masjid, the first mosque with ablution stations, a spirituality and formation hall and a halal kitchen on a U.S. college campus. Georgetown was also the first U.S. university to hire a full-time Muslim chaplain, Imam Yahya Hendi, 24 years ago.

The masjid, which opened its doors in fall 2019 and completed construction and design this year, provides a space for reflection, prayer, community and interfaith dialogue for Muslim and non-Muslim students at Georgetown. The masjid builds on the university’s commitment to interreligious understanding and care for the whole person, or cura personalis, in creating sacred spaces on campus and community for students of all faith traditions.

“At Georgetown University, they come to a unique place,” says Imam Hendi, director for Muslim Life. “They come to a place that cares for the whole person. They walk into the space that tells them they are not far from home. They are home.”

‘It’s My Second Home’

Imam Hendi first envisioned the masjid 12 years ago, and has worked with students, faculty, staff, donors and a design firm to realize the dream. The masjid offers five daily prayer services, educational programming and spiritual discussions, and a built-in community. For many students, the masjid also offers a place of solace and refuge to disconnect from their routines and connect with fellow Muslims.

Photos by: Phil Humnicky/Georgetown Univ.

Every element of the masjid’s design was carefully chosen. Outside the prayer space, the masjid offers two wudu’ stations (top row, left), lined in brilliant blue and red tile, where visitors can perform the ritual washing before entering the space. The blue traditional Arabesque tile patterns in the entrance evoke the sky; the carpet color on which visitors prostrate, dust: “We come from dust and to dust we shall return,” Imam Hendi says (top row, center and right). Its Abu Hamid al-Ghazali Spirituality and Formation Hall (bottom left) offers a community faith space lined with Islamic artwork and seating areas. The artwork and calligraphy in the musalla, or sanctuary, such as the 99 Attributes of God, tiles of glass hand-blown in Turkey to help visitors connect with God (second row, center), represent Islamic values of compassion, knowledge and communication.

For Aleena Maryam Dawer (H’24), the masjid was one of the main reasons she came to Georgetown. She and her parents were excited to see the amount of support for Muslim students while visiting campus, she says. Now, she visits the masjid every day after class.

Aleena Maryam Dawer (H’24) reads the Quran in the masjid.

“It’s like my little solace away from the chaos of university life,” she says. “It’s something that provides inner calmness and inner peace when you’re constantly in the hustle bustle of the Georgetown community, running around, going to lab, going to a lecture, getting food. When you come here, it’s a place of peace and belonging. It’s pretty much my second home.”

Roudah Chaker (C’24), a junior who commutes to campus, also finds the masjid to be the place where she spends the majority of her time on campus. Chaker transferred to Georgetown in fall 2021. She didn’t have a worship space at her previous university where she could pray and build a community. At the masjid, she’s found a vibrant community, a deepened faith and a space where she feels comfortable being her full self.

“I wear a hijab, and that’s always the first identity I’m seen as,” she says. “But in this one space, I’m seen as me. I’m seen as my personality. I’m seen as my intelligence. I’m seen as my heart and my soul. And this makes me feel safe, knowing that I can just be who I am.”

Chaker is a Muslim Life Fellow in Campus Ministry’s Muslim Life Office and attends events in the masjid, like a mental health series and Islam series led by Iman Saymeh, a residential minister in Campus Ministry and clinical social worker. Saymeh says the masjid is a “refuge” for students, an important space for interfaith dialogue, belonging and prayer.

“This is an opportunity for students to feel proud of who they are and their identity here on campus,” Saymeh says of the masjid. “It really promotes diversity and stands up for what Georgetown is promoting: togetherness, unity and building a sense of community.”

Students pray in the masjid’s musalla, or sanctuary.

Increasing Interreligious Understanding

The Yarrow Mamout Masjid is one of seven sacred spaces on Georgetown’s main campus — and one of three spaces for Muslim students to pray across Georgetown schools, including Muslim prayer rooms in Georgetown Law and the School of Medicine.

As the nation’s oldest Catholic, Jesuit university, Georgetown continues to find new ways to foster its values of interreligious understanding and cura personalis. The masjid is the latest example, says Fr. Mark Bosco, SJ, vice president for Mission & Ministry.

“We’re trying to form students to be people for others,” says Fr. Bosco. “And in doing that, it means we need to embrace interreligious dialogue. Coming to these different places, being invited by another student to come to the masjid, for example, whether you’re Muslim or not, invites us to explore the richness of Georgetown’s heritage and its deep commitment to our faith traditions.”

Dawer, who is on the Muslim Student Association (MSA) board, has helped plan recent interfaith discussions with the Jewish Student Association and with Sikh students. She said the events have helped students discover common ground and shared values, moving past perceived differences they often saw in the media.

“I think that there’s a constant talk about the differences, but the fact is that the similarities bring us together,” she says. “It really enriches us as a community, especially at a Catholic Jesuit university, engaging in conversations with students from diverse cultural and social contexts.”

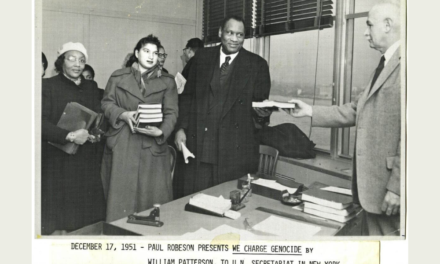

A Dedication to Yarrow Mamout

At the March 18 celebratory event, Georgetown formally dedicated the space to Yarrow Mamout, an enslaved man who bought his freedom, contributed to the neighborhood of Georgetown and continued to deepen and practice his Islamic faith in the 18th century. Washington, DC Mayor Muriel Bowser also issued a mayoral proclamation recognizing the Yarrow Mamout Masjid, and the DC Council unanimously approved a ceremonial resolution honoring Yarrow Mamout and recognizing the dedication of the masjid at Georgetown.

“We recognize, in naming our Masjid for Yarrow Mamout, a man of great strength, faith and perseverance. A person who fought against the racism and discrimination of his time, whose life was animated by his Muslim faith, a man who was integral to the foundation of this neighborhood and this city.”

Mamout was born in 1736 in West Africa, and was kidnapped by slave traders when he was 16 and sent to Maryland. A skilled brick- and basket-maker, Mamout worked hard to save money and buy his freedom. After facing many obstacles, and losing his money three times, he was finally able to buy his freedom in 1796.

Four years later, he bought land in Georgetown, worked to purchase his son and partner’s freedom, and helped others purchase theirs. Throughout his life, despite racism and religious persecution, Mamout remained committed to his Muslim faith. He wrote and spoke in Arabic. When he died, 38 newspapers wrote obituaries about him across the East Coast.

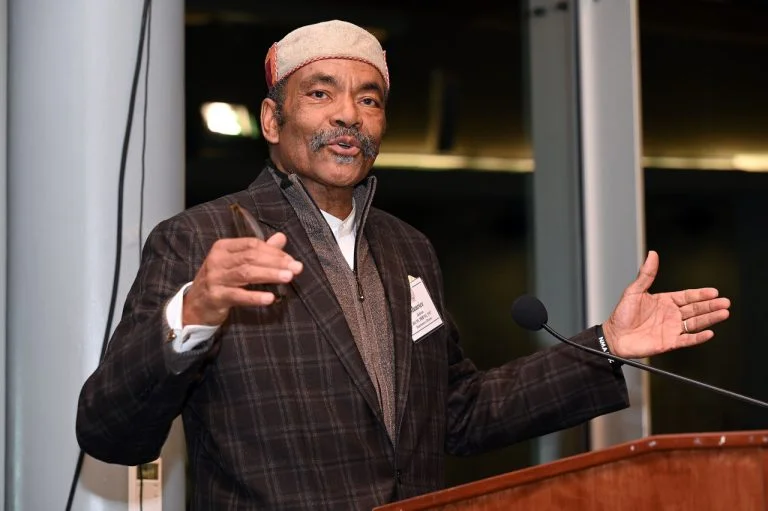

Maurice Jackson, associate professor in the Department of History, who worked closely with Imam Hendi to garner support from the DC community to establish the masjid. This fall, Jackson will teach the course “Islam and Black Americans” at Georgetown, and at Georgetown in Qatar the following spring.

“Here was this man in this city who was able to keep his religion, his faith, his language, his hopes for the future in the midst of all that,” says Maurice Jackson, associate professor in the Department of History, who wrote a biography about Yarrow in the event’s program. “So Yarrow represents a tradition of African Americans who have become Muslim and joined the religion because of their belief in the tenets of Islam.”

Imam Hendi said in choosing to name the masjid after Mamout, in consultation with Muslim students, faculty and staff, shows how American Muslims have been an integral part of U.S. history.

“The naming of the masjid reminds us American Muslims that we are a part of the fabric of the United States of America,” he says. “We have always been here. We are not newcomers to this country. We continue to contribute to it, and we will continue to engage it in the best of ways. And we American Muslims have to be an integral part of the national fight against slavery and against racism.”

Continuing To Build Community

In fostering interreligious dialogue in the masjid, Imam Hendi hopes to influence a class of graduates committed to a vision of peace and justice that they bring back to their communities. He also hopes to engage all students at Georgetown at the masjid.

“Come with your baggage, come who you are,” he says. “You’ll be embraced, you will be loved and you will be catered for. We’re all brothers and sisters in the love of God, in service of humanity, and in our commitment for compassion in this world.”