The iconic Bayswater bookstore’s story is one that was intertwined with Britain’s Arab diaspora over four decades.

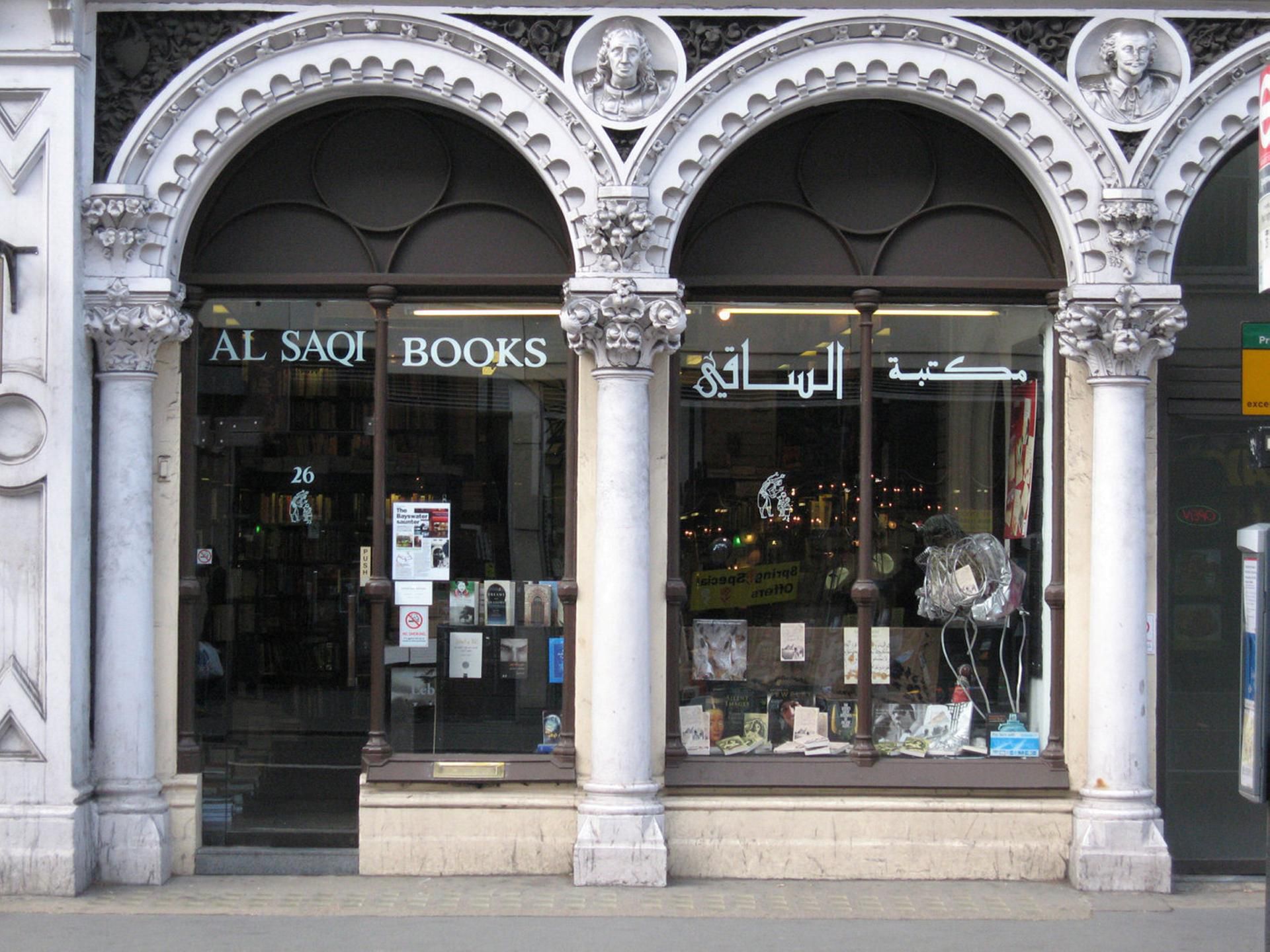

The oldest Arabic bookstore in London, and the largest Middle Eastern specialist bookshop in Europe, is set to permanently close its doors at the end of this month after gracing the centre of London for over four decades.

Upon hearing the news last week, award-winning Sudanese author Leila Aboulela called it “the end of an era” as she bid goodbye to a place that was part of her “intellectual makeup”.

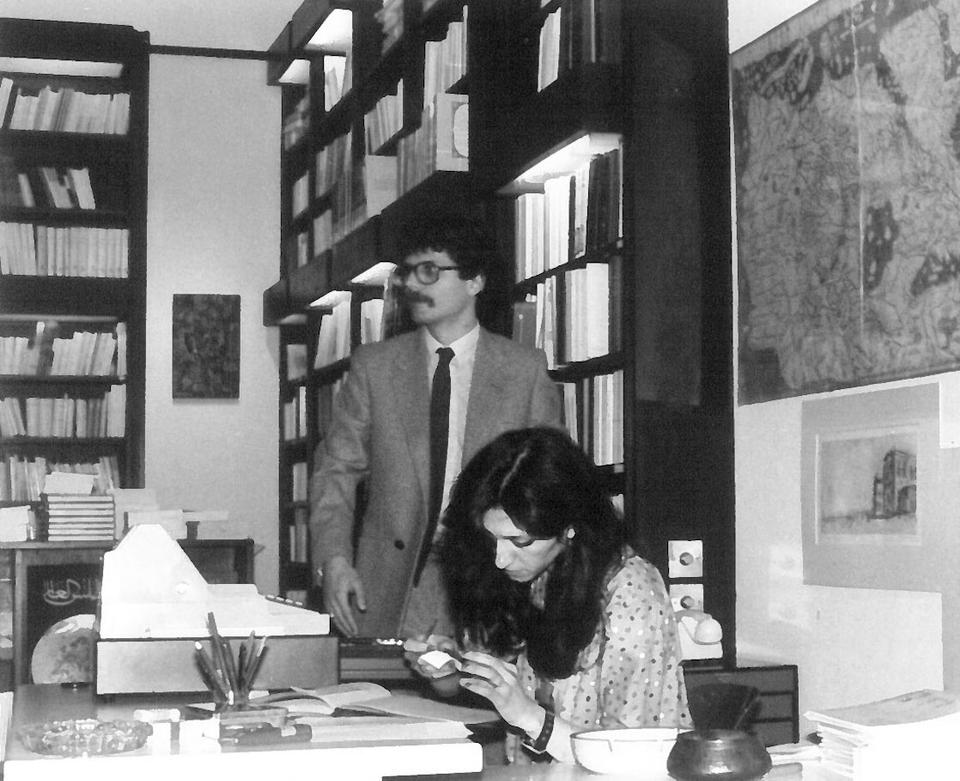

Al Saqi Books opened in 1978 and was the genius creation of friends Andre Gaspard and the late author Mai Ghoussoub. They both fled to London following the turmoil of the Lebanese civil war and created an Arab cultural and literary hub in the heart of trendy Notting Hill.

The buzzing Bayswater location has been a haven for the Arab community in London since at least the 1980s, and the focal point and constant over the years, many would say, has been Al Saqi Books.

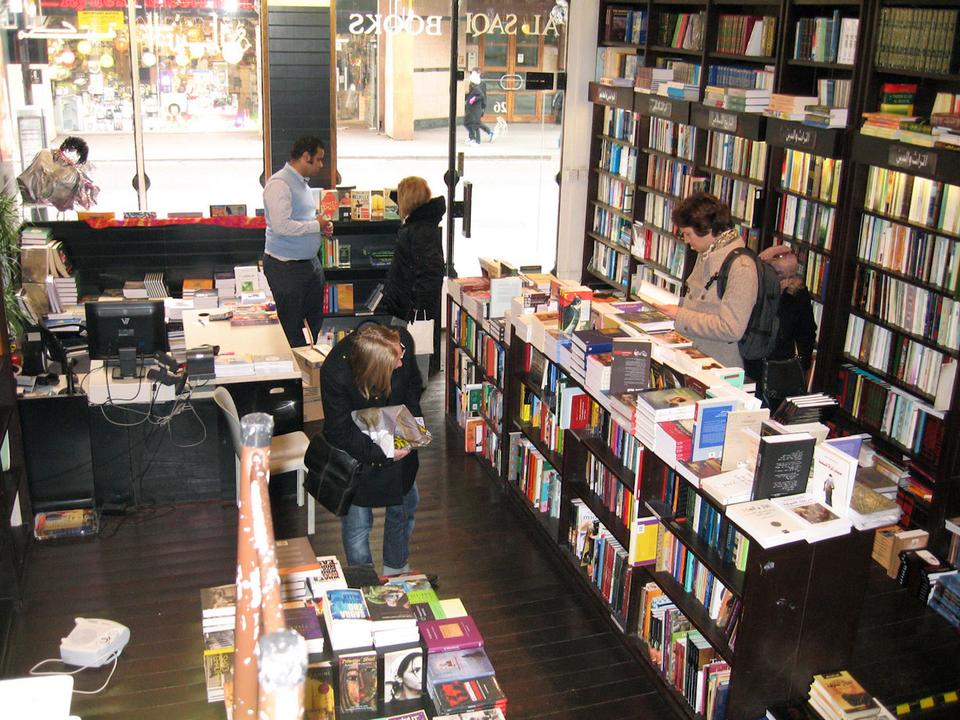

Not only does Al Saqi resemble an Aladdin’s cave of books featuring an array of diverse publications relating to the Middle East and North Africa, but it also has a significant history.

“After fleeing Lebanon as refugees, the founders Andre and Mai realised a unique opportunity to cater to the demand for Arabic books in London. There was a growing Arab diaspora and an interest from non-Arabs to learn about the Middle East and its history and culture,” Mohammad Masoud, Arabic Book Specialist at Al Saqi, told TRT World.

Literature and learning have traditionally held a central place in Arab culture, and Al Saqi nurtured that deep-rooted sense of identity for the diaspora.

“The meaning of Al Saqi in English means water seller. Just as the humble Middle Eastern water seller quenches the thirst of the desert dwellers, Al Saqi was intended as a metaphorical watering hole for those who were thirsty for knowledge and learning,” Masoud said.

In a recent Facebook post, Lynn Gaspard, the daughter of the co-founder Andre, said Al Saqi Books “stood for freedom of thought and expression, cultural diversity, exchange of views and empathy with all peoples”.

“Nearly forty years, hundreds of titles, numerous awards and two imprints later, that legacy lives on in our two publishing houses. We will miss operating alongside the bookshop but look forward to the next chapter in Saqi’s history from our new office premises in West London.”

Al Saqi Books’ co-founders Andre Gaspard and Mai Ghoussoub in the late 1970s. (Al Saqi Books)

Lebanon to London

Al Saqi was established in London at the time of the Lebanese civil war, which took place from 1975 to 1990. In the context of war and turmoil, it became difficult to access books that were contrary to whatever administration was in power. In addition, censorship and propaganda made it almost impossible to obtain books written by authors with varying views and stories.

Al Saqi became famous for its revolutionary stance to stock works from censored and minority authors, establishing a reputation as a place where one could get hold of books unavailable elsewhere.

In 1983, Al Saqi launched a publishing arm that gave a platform to many more voices and perspectives. And in 1988, the founders opened a sister company, Dar al Saqi, in Beirut.

Due to its bold position and promotion of Arab identity and culture, Al Saqi continues to hold a special place in the hearts of many worldwide.

“London will never be the same without the Al Saqi Bookshop on Westbourne Grove. A beautiful place that for decades supported Arab writers. This is where exiled Arab intellectuals went to buy their books, where one could find books banned in the Middle East and where warm, open-minded Londoners went to find a cookbook to teach them how to make Koshari!” Aboulela said.

Al Saqi not only offered an array of diverse Arab publications, but also established a reputation for stocking works that were censored back in the Middle East. (Al Saqi Books)

Ricardo Karam, a Lebanese TV personality, wrote a heartfelt message on Facebook.

“The bookstore has witnessed the wars and revolutions of the region and trusted and kept up with changes in our world. Year after year and despite challenges and threats, it has remained committed to those who still believe that books are the heart of culture; they can shape generations, nurture enlightenment and inspire heroes of change.”

There is a rich history attached to the founding of the bookstore and its Bayswater location, which has a long-standing connection to the Arab diaspora. Masoud recalled that it used to be next door to the famous Al Kufa Gallery, owned by the renowned Mohammad Makiya, one of the top architects of former Iraq president, the late Saddam Hussein.

“The gallery was a centre for Islamic and Arab art and a place where those interested in Arab heritage could meet. Having these two Middle Eastern cultural anchors side-by-side reinforced this corner of town as a focal point for Arab culture.” Masoud said.

The legacy of Al Saqi goes beyond its literary contribution; it is also part of the essence and history of London. The bookshop not only attracted Arabs but also was the hangout of language lovers, people interested in the Middle East, journalists, university students and even celebrities.

“Al Saqi has many celebrity clientele, including authors we have helped support, publish and promote. Also, being situated in the heart of Notting Hill, we have many famous neighbours who might drop by,” Masoud said.

The last chapter

Al Saqi has long been a place for people to connect and culturally revitalise themselves, but sadly when it closes its doors in a few days, it will leave a massive hole in many lives.

The shuttering of this iconic bookstore is a result of several factors, including the economic impact of the pandemic, Brexit, rising production costs and shipping, and changed shopping habits of customers.

Film producer and director Daniel Jewel, who is making a documentary about the economic crisis in London and its impact on communities and culture, features the closing of Al Saqi in his film as a prime example of gentrification in action.

“With rising costs in a post-Brexit and post-pandemic world, we are seeing more and more small businesses and cultural strongholds closing down,” Jewel told TRT World.

“As a result, developers and chain stores come in as they have the funds to plug the gap. But sadly, this creates a monoculture and what I call ‘blandification’ where all high streets look the same. Once that authenticity and culture are lost, it is gone forever.”

A regular visitor to Al Saqi, Jewel loved the store because it was a window into a world for non-Muslims interested in the Middle East and its history and heritage. “You could find authentic books written by Arabs and Muslims, rather than what’s represented quite negatively in the media. It was a place of cross-cultural fertilisation and somewhere that helped create mutual understanding,” he said.

“Sadly, when it closes, we will have lost one of London’s cultural gems.”

Al Saqi’s closure is not only about losing this historical treasure for the Arab community and beyond. It also signifies a changing world – where people are less physically connected, and grassroots and authentic culture becomes less valued and replaced with mass production and online shopping.