Photo ©:

A marketing executive in the greater Chicago area got a call from a friend about a high school football team in Dearborn, Michigan, that had won a spot in the state semi-final football championship.

“The amazing thing about this team,” Rashid Ghazi, a partner at Paragon Marketing Group, said at TEDx Traverse City 2012, “is they fast from sunrise to sunset – no food or drink.”

The team, the Fordson High School Tractors, played for a public American high school founded by Henry Ford, where the student body was 98% Arab American Muslim. It occurred to Ghazi that the Tractors’ story might be the perfect vehicle for changing Islam’s image in America. Although it took seven years, Ghazi, a Muslim American of Indian descent, went on to direct and produce an award-winning documentary about the team.

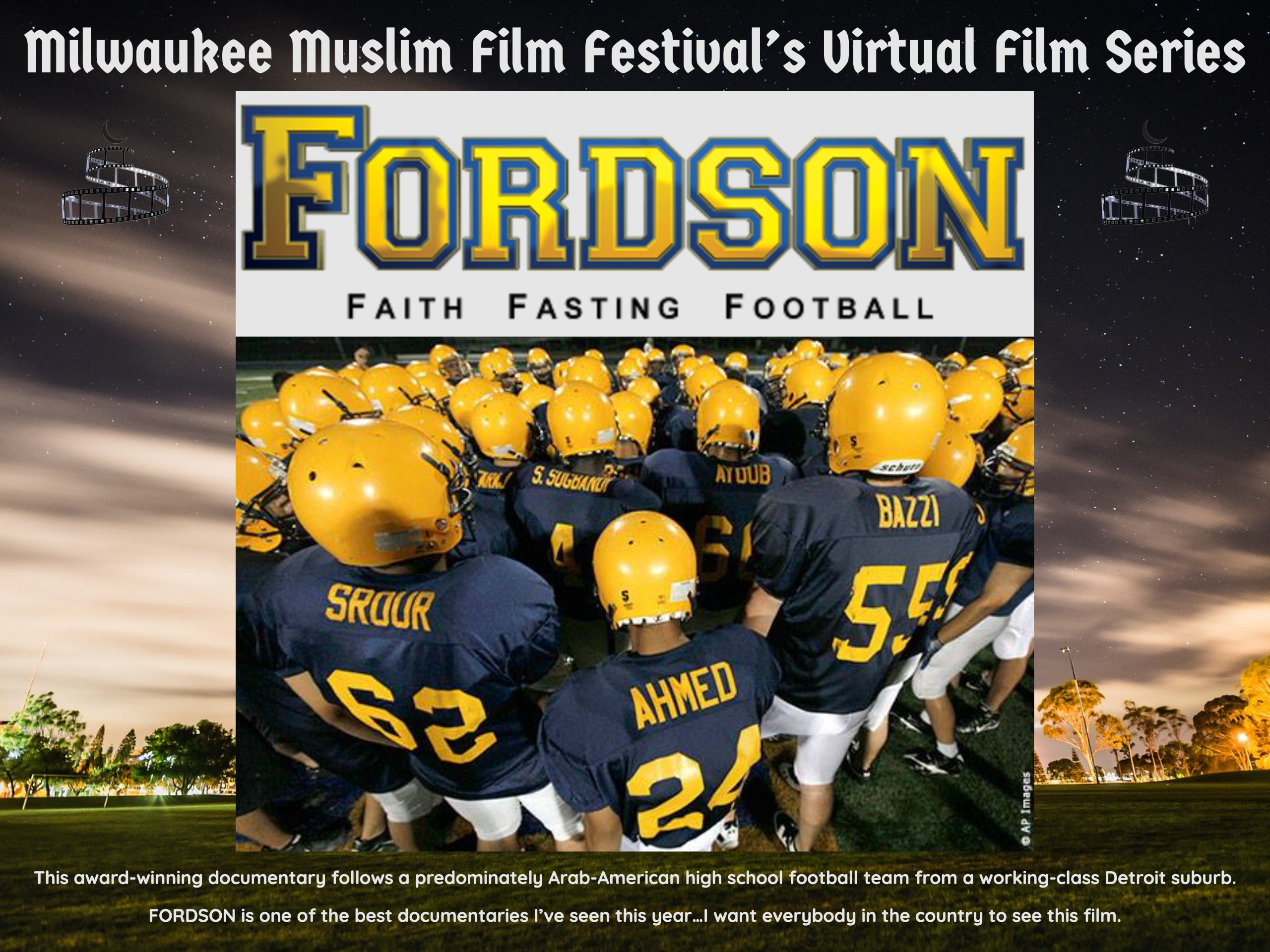

Milwaukee Muslim Film Festival will feature Ghazi’s 2011 documentary FORDSON: Faith, Fasting, Football at 7 p.m. Saturday, April 10, and Ghazi speak at the talkback.

An all-American sports story, Ghazi’s film follows the team of Muslim athletes from a working-class Detroit suburb as they practice for the big game during the last ten days of Ramadan. The movie reveals a community holding onto its Islamic faith and structuring its identity in post-9/11 America. It shows how this group of Arab Americans integrated football into their way of life, their culture and their ethnicity.

Register for the free screening and talkback with the film director. Or view the talkback with Ghazi on the MMFF’s Facebook and YouTube pages at 8:40 p.m.

Repositioning Islam

As someone who specializes in brand marketing and advertising, helping large companies position their brands, Ghazi looked at Islam and considered how it was perceived in the marketplace in the United States.

“Most brands spend hundreds of millions of dollars aligning themselves with celebrities – athletes like Michael Jordan for Nike and Olympian skier Lindsey Vonn for Red Bull, or a beautiful entertainer like Beyonce who endorses L’Oreal. For Muslims, if we look at our brand, who speaks for us?

“Over the past 20 years, since the Iran hostage crisis, it’s people like Saddam Hussein, Muammar Gaddafi and Osama Bin Laden who have represented Islam. That wouldn’t be a problem if most Americans knew who Muslims were, he said. “According to Time Magazine, 62% of Americans do not personally know a Muslim.” (Now the percentage of Americans who personally know Muslims is about 50%, according to the Pew Research Center.)

Fordson’s Director Rashid Ghazi

As a Muslim American father, thinking about what the future holds for his daughter and sons, Ghazi was eager to address this branding problem. Inspired by Alex Haley’s Roots and The Diary of Anne Frank, he sought to tell the Muslim American story to fellow Americans in “a contextual and impactful and entertaining way,” he said. “And what is more American than football! Leveraging football was a way to talk about race, religion, Sept. 11, immigration and the American dream.”

He began pursuing the rights to make the film from the Dearborn Public Schools Board of Education in 2004. It wasn’t until 2009 that he acquired the rights. But he still didn’t have funding.

“My wife and I had saved enough money to build a house, but when we couldn’t get funding, we sold all our stocks, put off building a house and funded the movie ourselves.”

Ghazi founded North Shore Films in 2009 and co-produced FORDSON: Faith, Fasting, Football with Quraishi Productions, LLC, a partnership between journalist Ash-har Quraishi and his wife Basma Babar-Quraishi. After being turned down by multiple film festivals, it was accepted at the Traverse City Film Festival hosted by Michael Moore, where it won the Grand Jury Award for Best U.S. Documentary. It was screened by the U.S. State Department and honored by then U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton.

AMC Theaters distributed the film nationwide on Sept. 9, 2011, in time for the 10-year anniversary of 9/11. Since then, it has been televised in more than 30 countries and sold to universities across the country.

When Ghazi and his wife heard that an Islamic high school in Texas was not allowed to join the Texas Association of Private and Parochial Schools conference “to play against teams of Christian and Jewish kids,” they sent 218 DVDs, one to each TAPPS school, along with a letter, to rectify the situation.

In an essay about Ghazi’s film in the Journal of Sports History, Dr. Zachary Ingle of the University of Kansas wrote: “This obscure documentary indeed has the potential to change people’s minds and make the U.S. a better place, a more tolerant country, one that embraces other cultures and religions within its borders.”

Muslim football players today find public schools welcoming

Although Islamophobia and stereotyping are still rampant by all accounts, Muslim athletes at public high schools say they find their schools welcoming.

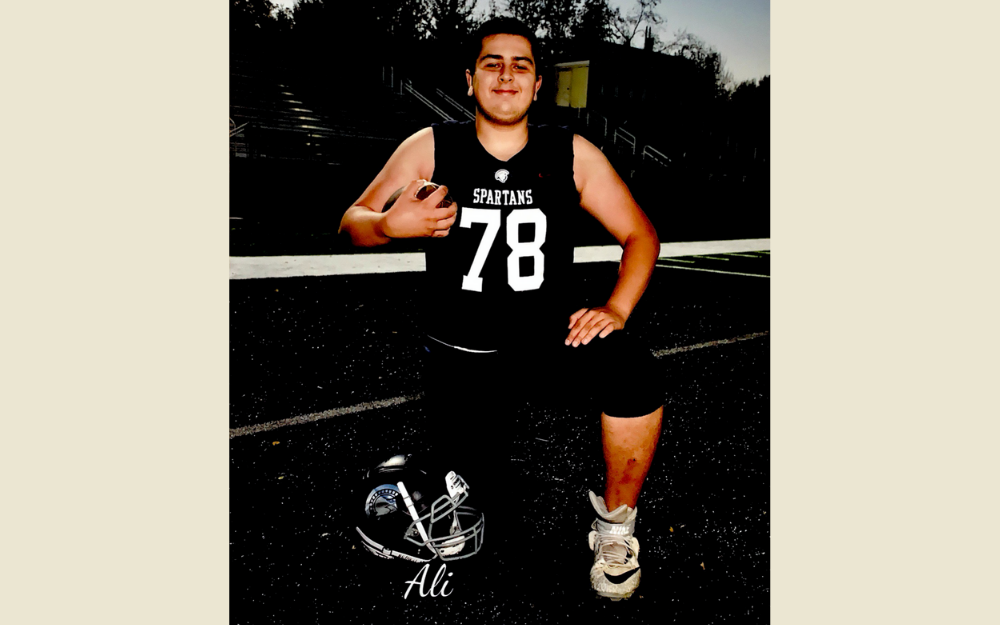

Ali Altahat, a Brookfield East junior who plays on the offensive line as right tackle, is the only Muslim on his team. He has been playing football in the Elmbrook School District for the past five years.

“Fortunately for me, I have a very supportive team, the 16-year-old said. “The coaches completely understand if I have to take a religious absence. They have been totally understanding and supportive in all the years I have played football. I haven’t run into any issues regarding religion.”

Although Ramadan starts next week, Altahat doesn’t expect it to be difficult. “We are in off-season workouts right now, doing strength and conditioning, trying to get as strong as possible for the season. There is not much cardio involved and the sessions only last about an hour, so it is not too hard.”

When Ramadan overlaps with football season, it is a different story, he said. “When I first started playing in 7th grade, we started practicing towards the end of the summer and Ramadan overlapped for about two weeks. In the pads and the heat, it was definitely tough,” he said.

Brookfield Central High School wide receiver Adam Lahrache, 17, said “the best thing about football is that the team feels like a family and it is a really fun thing to be a part of.” Lahrache is one of two Muslims on the team.

He also finds the coaching staff and teammates accommodating, he said. “Like the team meals, if they are having pork, they always have a non-pork option.”

Lahrache also remembers when Ramadan overlapped with the beginning of football season when he was in middle school. “It was a challenge to get through. You don’t have energy because you haven’t been eating and you are watching your teammates chug water.”

Also a sprinter on the track and field team, Lahrache is facing the starts of both track season and Ramadan. “I do short sprints so it is not as difficult as if I were doing distance,” he said.

At Fordson High School, with its predominately Muslim team, they implemented night practices during Ramadan in 2010.

Neither Altahat or Lahrache expect any special treatment, they both said. There is a lot of balancing between additional demands on their time (Quran classes or Sunday school), athletic practice and a demanding academic schedule.

Ali Altahat, 16, plays tight end for Brookfield East High School.

Balancing academics, football and faith

“Sometimes we have to make difficult decisions,” said Altahat, who is taking AP biology and AP psychology. “We are called student athletes because being a student comes first. We have to make sure we are maintaining those good grades.

“My religion is something internal. It gives me morals that I follow. I don’t see it as something that creates a need for others to shift schedules or to create a separate practice plan,” he said.

“As student athletes, we have to be really good at time management,” said Lahrache, who keeps assignment deadlines on his phone. His favorite class is AP Government and Politics.

Lahrache volunteers as a teacher’s helper at Sunday school at the Islamic Society of Milwaukee – West in Brookfield and attended Quran class during the week. Both Altahat and Lahrache attended classes at ISM-Milwaukee when they were younger but were not able to continue in high school due to conflicts with practice.

In addition, student athletes have pressure to improve their stats if they hope to play on a college team.

“Stats are everything in football, especially when you are applying to colleges,” Altahat said. “They look at your height, your weight, how fast your 40-yard dash is, how much you can bench, how much you can squat—there are a lot of numbers that go into it.

“I am always working to improve them. That’s your Number One goal as a player. When you fill out those stats when you apply to college, you want to feel you are in a good position to succeed.

“Fortunately, I am a good size. A lot of my teammates are jealous. I’m a big dude, 6’3” and 280 pounds. That is the peak size you can ask for in my position.

“You take whatever is with you and you run with it,” he added. “I have seen a lot of smaller guys do big things that big guys can’t do. Size is something that can help you. But in the end, it is not the size of the dog in the fight but the size of the fight in the dog.”

Altahat hopes to pursue football in college and study business, maybe with his favorite team, the University of Wisconsin Badgers.

Lahrache said, “If I get the opportunity to continue football past high school, I definitely would.”

Regarding his stats, Lahrache “sets lofty goals” for himself, he said. “I’m a little on the smaller size so I have to be quicker and faster than most.” When pressed, he confessed, “I’d say I’m pretty fast.

“I always have religion on my mind through everything,” he added. “I believe Allah is with me when I’m playing. Every time I have a success, I owe it to him. I try to keep that in mind and stay grateful.”

Altahat and Lahrache both said having supportive parents is something they are grateful for.

Altahat’s parents, Rana Alhourane and Zaid Altahat, are “his biggest fans, my mom being my number one fan. She is always recording me, always hooting and hollering in the stands, sharing game pictures all over the place.”

Lahrache appreciates how his parents, Nawal Ilili and Hassan Lahrache, “are always there. Usually at least one of them is at everything” – football games and track meets.

Senior Adam Lahrache, 17, is a wide receiver for Brookfield Central High School.