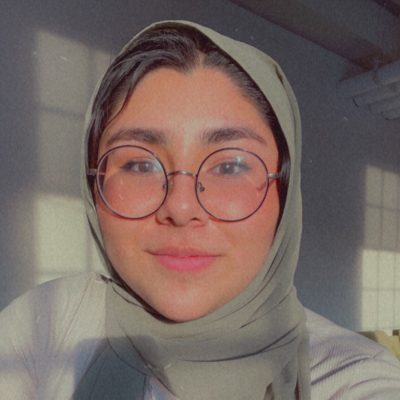

UW-Madison Center for Religion and Global Citizenry’s 2022-23 Interfaith Fellows includes six Muslims: (top) Hali Jama, Ghaida Edreis and Mohamed El Ragaby; (bottom) Rida Ali, Karam Gursahani and Najma Hurre

As the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Center for Religion and Global Citizenry welcomes six Muslims among its 2022-23 Interfaith Fellows, a cohort of 26 students of diverse faith backgrounds, Wisconsin Muslim Journal interviewed recent Muslim Interfaith Fellows, CRGC director and a program coordinator to learn what’s in store for them.

The yearlong Interfaith Fellows Program “trains undergraduate students to become more knowledgeable about different religious traditions and more skilled at communicating with people from other religious backgrounds,” CRGC’s website explains. The CRGC’s goal is to provide Fellows, and through them other students, “with the knowledge and skills to surmount the barriers of religious difference and to become interfaith leaders,” whatever careers the future might hold for them.

The CRGC Interfaith Fellows’ experience in the program is expected to empower the new Fellows to change their campus and impact their faith.

Shaping campus culture while growing in faith

As a 2021-2022 Interfaith Fellow, Storay Wardak, a Muslim, found herself with colleagues of multiple faiths—Christians, Jews, Hindus and others—in the office of a high-ranking UW-Madison administrator, advocating for observant religious students.

Storay Wardak is a senior in Religious Studies.

Tahseen Shaik, 23, of Franklin recalled how a trip with Interfaith Fellows to a Sikh temple showed them their shared values. “An English translation of Sikh scripture was on the screen. I was reading along and realized it sounded like the Qur’an. As we were driving back, we were all talking about the commonalities in our faiths. In our discussions as Fellows from all different religions, the more we talked about things, the more we realized we share morals and many beliefs.”

Shuaib Aljabaly will graduate in December in Computer Science.

“This was particularly pertinent to me,” said the 22-year-old UW-Madison senior. “Finding access to places on campus to make wudu (a ritual that requires washing of face, hands, arms and feet before prayer) five times a day and looking for places to pray, meeting the demands of being a student on top of what is required during Ramadan—the anxiety Muslim students feel about asking teachers for extensions (during fasting), choosing between taraweeh, night prayers, and studying.” Students of other faiths also needed understanding from the administration about their needs.

“We were able to speak as interfaith fellows about what it means to be religiously accommodating to students,” Wardak said. “Some accommodations were made. It was nice to make an authority figure on campus aware of these issues.”

Tahseen Shaik graduated in December with a degree in neurobiology.

Senior Shuaib Aljabaly, 22, from Michigan, said his brief experience of being an Interfaith Fellow motivated him to be a better Muslim. “With other Muslims, we do what we do. In deep discussions with the fellows, they asked why. To answer their questions, I needed better understanding.” (Aljabaly withdrew from the program early due to the demands of being a student and college athlete, traveling frequently with the cross-country and track teams.)

A new model for a new time

CRGC, established in 2017, grew out of the Lubar Institute for the Study of Abrahamic Religions, which closed in 2016, said CRGC director Ulrich Rosenhagen, Ph.D., a lecturer in Religious Studies and an ordained Lutheran pastor.

The Lubar Institute was a direct response to 9/11, he explained. Sheldon Lubar, a Milwaukee-based venture capitalist and philanthropist, had a business meeting scheduled in the Twin Towers on the afternoon of Sept. 11, 2001. “He was in New York and saw what happened. He drove home to Milwaukee and called former UW Chancellor Wiley two days later. He wanted to do something to support interfaith understanding. Wiley connected him with history professor Charles Cohen who had the idea of creating a center for dialogue between the Abrahamic faiths—Christianity, Judaism and Islam.”

Cohen heard about Rosenhagen, a trained Lutheran pastor from Germany with a Jewish wife. He brought him in to facilitate and work with students.

Ulrich Rosenhagen, Ph.D., director of the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Center for Religion and Global Citizenry

When funding for the Lubar Institute ended in 2016, “I pitched to the dean a center that would go beyond the Abrahamic paradigm,” said Rosenhagen. “One of the first things people would ask is, ‘Why do you have interreligious dialogue in America and exclude Buddhists, Hindus, agnostics and atheists?’ We live in a world where we are global citizens. In order to function and be citizens in a global world, we need to know about religion.

“When I pitched it, I quoted Madeline Albright, who said in her memoir that when she was at the State Department, she had tons of advisors in economics, in politics, in everything, but no one could answer the simplest religious questions.”

In the new model, Interfaith Fellows of various majors and diverse faith backgrounds participate together in weekly meetings throughout one academic year. “It’s a four-step approach,” Rosenhagen explained. “First, the students get to know each other so that we’re building trust. We talk about dialogue rules; then learn about the basics of the different traditions involved that year. In the third phase, they go out on experiences together to visit sacred sites. Last year we had an overnight retreat at a monastery. Finally, they organize events on campus, interact with other students on campus and share what they have been learning.” The Fellows also post blogs about their experiences.

After they graduate, the Fellows “go out and do big things,” Rosenhagen continued. “We have student who are now becoming partners in law firms of a thousand people, students who go into the medical field, students who do chaplaincy, including a Muslim chaplain and an architect who designed multi-faith spaces.”

UW-Madison’s Class of 2022 included 29 students who had gone through this year-long program as part of their university experience, he added.

Fellows dined together at Taste of Sichuan and celebrated their year together.

The presence of Muslims

Program coordinator David Schulz, 30, who was himself a Lubar Fellow, has noticed the Muslim Interfaith Fellows “have a real desire to represent their tradition in an authentic way, to really clue people in on their experience of Islam and how it is different from public perceptions. There’s a real desire to represent the tradition the way they see it.”

At the same time, being in such a small minority of students on campus, it important to remember there is more than one way Muslims think, Storay added. During Spring 2022 semester, she was the only Muslim in the fellowship. When asked about Islam, she said she always prefaced her comments with, “This is what I think.”

Interfaith Fellows listen to Dekila Chungyalpa who spoke about climate change from an interfaith perspective.

Being the only Muslim in many discussions, Storay felt the weight of correcting many misunderstandings about Islam and Muslims in the media and society. “If I were Buddhist, practicing a religion most people consider peaceful, even if I was the only one, I don’t think I would feel the same pressure,” she said.

“I learned to better articulate my own understandings and beliefs,” said Shaik, who graduated in December with a major in neurobiology and a minor in public health. “There are a lot of things I grew up with that seemed like common sense. I didn’t always know the reason but practiced it anyway. When people ask you what it means, well, for me, I had to learn more about my faith.”

Fellows and friends spent two days practicing silence, meditation and yoga.

Shaik would respond, “Let me get back to you.” Then she went to the Qur’an to find answers. “I tried to give better answers and I learned to better explain my faith.

“In our late teens and early twenties, we’re all growing and learning so many things,” she added. Sharing views about topics like death and afterlife helped the Fellows gain insights on commonalities and differences in perspectives. Participating in the fellowship with an open mind creates an atmosphere for everyone to learn about each other, she said.

Moments of growth in understanding “are beautiful to watch,” Rosenhagen commented. He recalled a moment he observed when a Muslim student from Gambia and an American Jew were having a conversation. The Jewish student explained he was a “Jewish atheist.”

“This doesn’t make sense to me,” the Muslim student responded. “How can you be a Jew and an atheist? No Muslim would ever say, ‘I’m an atheist Muslim.’”

The beauty of this conversation was seeing the discovery process of the other and yourself, “these moments of deep learning that come up in dialogue,”Rosenhagen said.

New developments

With record numbers of applicants, the program is growing, Rosenhagen noted. “Last year we accepted 15 Fellows. This year it’s 26.

“This year we are trying to move the program closer to the diversity efforts on campus, bringing people into conversation about belonging, inclusion and respect for the other, dealing with intersectionality and other diversity issues,” he said. “It is good for religion to be more a part of those conversations than it has been in the past.

“Many students have a religious identity that is important to them. When they come to campus, it’s something that is not officially addressed. It is a big problem to exclude religion from the question of identity and belonging. It helps them to have a community where they can think about those issues. ”

The Lubar Institute addressed the question of its day, how to make peace among the Abrahamic religions, Rosenhagen said. “Now the question is how can we create an inclusive, diverse campus that reflects society at large so that we can create a community bound by commonalities but also respectful of differences. How can we imagine society in the 21st century.”

Applications for the 2023-2024 CRGC Interfaith Fellowships open in March.

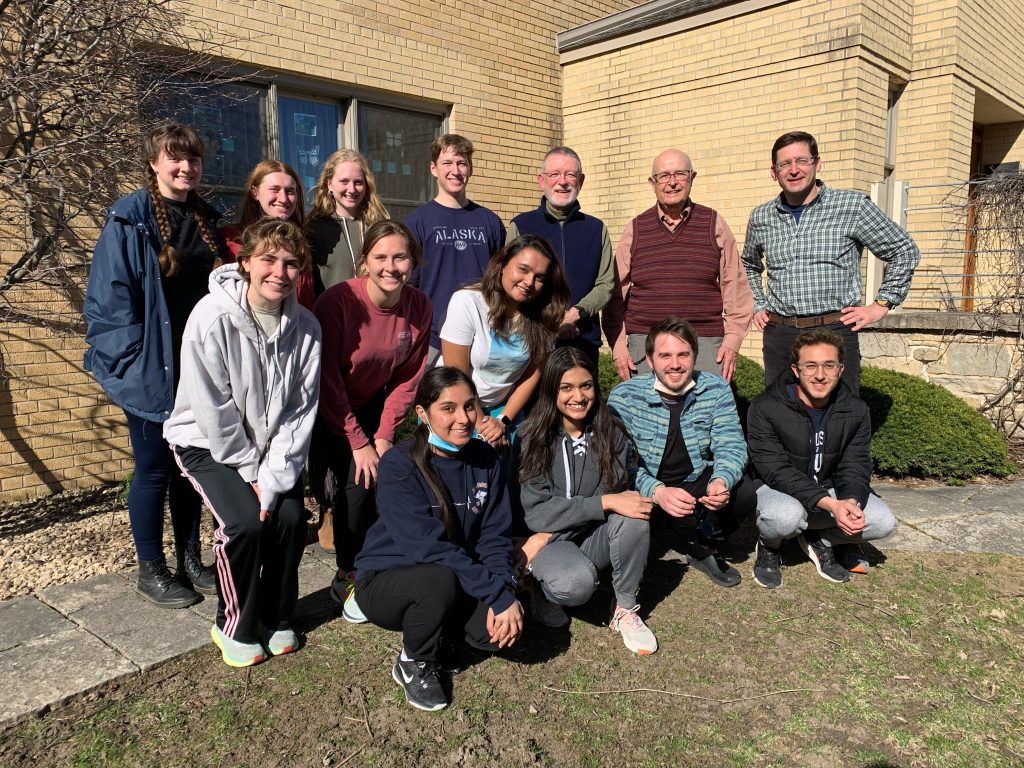

2020-2021 Interfaith Fellows included three Muslims (left to right): Osama Fattoub of Middleton, Mukadas Abdullah of Waukesha and Yaseen Najeeb of Milwaukee.