CAIRO (AP) — Shortly after Kholoud al-Faqeeh was appointed judge in an Islamic religious court in the Palestinian territories, a woman walked in, laid eyes on her and turned around and walked out, murmuring that she didn’t want a woman to rule in her case.

Al-Faqeeh was saddened, but not surprised — people have long been accustomed to seeing turbaned men in her place. It was only in 2009 that she became one of the first two women appointed in the West Bank as Islamic religious court judges. But she sees her presence on the court as all the more important since it rules on personal status matters ranging from divorce and alimony to custody and inheritance.

“What was even more provoking is that these religious courts are in charge of women’s cases,” al-Faqeeh said. “A woman’s whole life cycle is before these courts.”

Women like al-Faqeeh are increasingly carving out space for themselves in the Islamic sphere and, in doing so, paving the way for others to follow in their footsteps. Around the world, women are teaching in Islamic schools and universities, leading Quran study circles, preaching and otherwise providing religious guidance to the faithful.

___

This story is part of a series by The Associated Press and Religion News Service on women’s roles in male-led religions.

___

The formal ranks of Islamic leadership remain largely filled with men, but while women don’t lead mixed-gender congregational prayers in traditional Muslim settings, many say they see plenty of other paths to leadership.

“When it comes to knowledge, the leader who is the religious scholar, the spiritual guide, the one who is teaching people their religion … that can be done by women or men, and historically always has been,” said Ingrid Mattson, the London and Windsor Community Chair in Islamic Studies at Huron University College in London, Ontario.

There are diverse views across the different regions, cultures and schools of Islamic thought about the permissibility and scope of women’s leadership roles in the faith.

Some of the Prophet Muhammad’s traditions and practices were preserved and transmitted by the women closest to him, such as his wives. Many women say that provides a foundation they seek to build on.

Mattson said that people always ask whether a woman can be an imam, but that framing reflects a Western context focused on the weekly congregational prayer rather than “what our Islamic heritage did in terms of providing religious leadership across society to meet many different needs.”

Aziza Moufid, a 40-year-old in Morocco, is one of those who have taken up the mantle of leadership within the faith, in her case by serving as one of the country’s “mourchidat,” or female religious guides.

The “mourchidat” are trained at an institute for male and female students founded by and named after Moroccan King Mohammed VI. Women graduates teach religion classes and answer women’s questions at mosques or during outreach work in schools, hospitals and prisons.

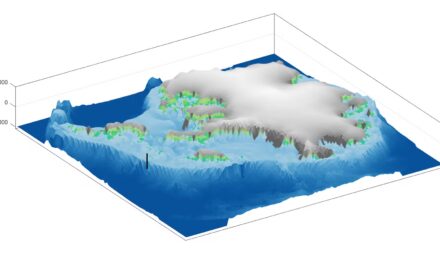

FILE – In this Tuesday, March 29, 2016, photo, Islamic court judge Kholoud al-Faqeeh poses for a portrait during a break at the court in Ramallah, West Bank. In 2009, she became one of the first two women appointed as religious court judges. She sees her presence on the court as all the more important since it rules on matters ranging from divorce and alimony to custody and inheritance. (AP Photo/Dusan Vranic, File)

Moufid, who recalls looking up to the female university professors who taught her Islamic studies, has been working as a guide mostly via WhatsApp during the pandemic. She uses the platform to explain sayings of the prophet to children; to help women learning to memorize and recite the Quran; and to counsel teenage girls about a myriad of topics from modesty to prayers to menstruation.

“There are sensitive issues that some of them may not dare discuss even with their mothers or sisters,” Moufid said. “But there’s no such shame between us. I tell them, ‘I am your sister. I am your friend. I am your mother.’”

Mohammed VI institute director Abdesselam Lazaar, who is a man, said the services of the “mourchidat” have been in high demand: “The women here in Morocco are very keen on memorizing the Quran and learning about religion.”

Half a world away in the United States, Samia Omar, who became Harvard University’s first Muslim woman chaplain in 2019, said female students there similarly appreciate being able to bring questions about things like menstruation to her instead of to a man.

Omar also sees herself as saving them from being taught a version of Islam devoid of discussion of their rights.

“I’m serving and teaching these young girls and women the way I hope other women will help teach my daughters later,” she said.

Omar didn’t always plan to become a religious leader. But the twists and turns of her life, including an abusive marriage, a divorce and losing a daughter to cancer, led her to the calling she now practices alongside her current husband, who also serves as a Muslim chaplain.

During the divorce, some at her mosque tried to dissuade her from turning to the legal system. She ignored that pressure and ultimately won full custody of her kids, but the experience left Omar feeling that some men exploit the religion to oppress women.

That can have grave spiritual consequences, Omar said: “Many young women don’t understand that we’re important in Allah’s eyes.”

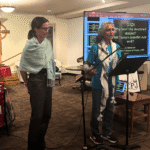

Samia Omar, Harvard University’s first Muslim woman chaplain, reads through “The Chain of Prophets” at the school’s office for Muslim chaplains in Cambridge, Mass., Nov. 30, 2021. Omar organizes a weekly discussion group for Muslim women on campus. (Aysha Khan/Religion News Service via AP)

Many in the U.S. have advocated for a larger role for women in mosques, from better prayer spaces for female worshippers to more seats on governing boards and a more friendly mosque culture. Some are also calling for a more decentralized leadership model at mosques, one that includes a paid female resident scholar in addition to a male imam.

While there is hope for such advances, “things are not great for women in leadership … in our sacred spaces,” right now, said Tamara Gray of Rabata, a nonprofit working to empower Muslim women to imagine themselves as leaders, scholars and teachers.

Change takes “a lot of patience and a lot of discussion and a lot of just being able to be courageous,” Gray said, adding that Islamic scholarship by women is sometimes met with distrust in Muslim communities.

To that end she founded the Minnesota-based nonprofit, whose programs include online courses in Islamic sciences. Through virtual gatherings focused on spiritual growth and worship, Gray said, women are able to experience being in a sacred space and then “go back to their own mosque and insist, really, that their mosque make them feel valued, respected, seen.”

During a recent virtual event joined by dozens of women, there were tears, laughter and ululations as the group celebrated Gray’s receipt of a certificate authorizing her to teach certain sayings and traditions of the prophet.

“The words of the prophet … they are weightier than a mountain of gold,” Gray told the group.

Promoting women’s spiritual leadership is crucial to keeping Muslims connected to their faith in America, in the eyes of Celene Ibrahim, a chaplain who researches gender and Islam.

“You can’t carry this on your own,” Ibrahim said, referring to male religious leaders. “This is a big task, and it’s an all-hands-on-deck kind of task.”

Al-Faqeeh, the judge, said that women’s long absence from judgeships in the Palestinian Islamic court owed in part to custom and to the fact that many viewed the post “as a religious position, like that of an imam.”

On the contrary, she said she saw it as a judicial one that relies on the rulings of the Islamic Shariah, and argued that there are no reasons to exclude women.

There were bumps in the road, both big and small, after her appointment, as some male judges and court employees seemed less than happy about it. Opposition also came in the form of a Friday sermon that she did not attend but in which, she was told, the speaker railed against allowing women to hold the position.

But things have gone smoother since, and she often senses relief on the part of women with cases before the court who feel they can talk openly to her about sensitive personal issues. “The once-impossible dream became possible,” al-Faqeeh said.

Reem Shanti, 40, who recently applied to become a judge on the religious court and considers al-Faqeeh a role model, said the appointment of women has opened up a world of possibilities for her and others.

“It provided women with an incentive,” Shanti said, “and gave them a strong push.”

___

Khan reported from Boston. Associated Press journalist Mosa’ab Elshamy, in Rabat, Morocco, contributed.

___

Associated Press religion coverage receives support from the Lilly Endowment through The Conversation U.S. The AP is solely responsible for this content.