In the book of Genesis, God bestows a new name upon Abram – Abraham, a father of many nations. With this name and his Covenant, Abraham would become the patriarch of three of the world’s major religions: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Connected by their mutual – if differentiated – veneration of the One God proclaimed by Abraham, these traditions share much beyond their origins in the ancient Israel of the Old Testament. This Very Short Introduction explores the intertwined histories of these monotheistic religions. . . .

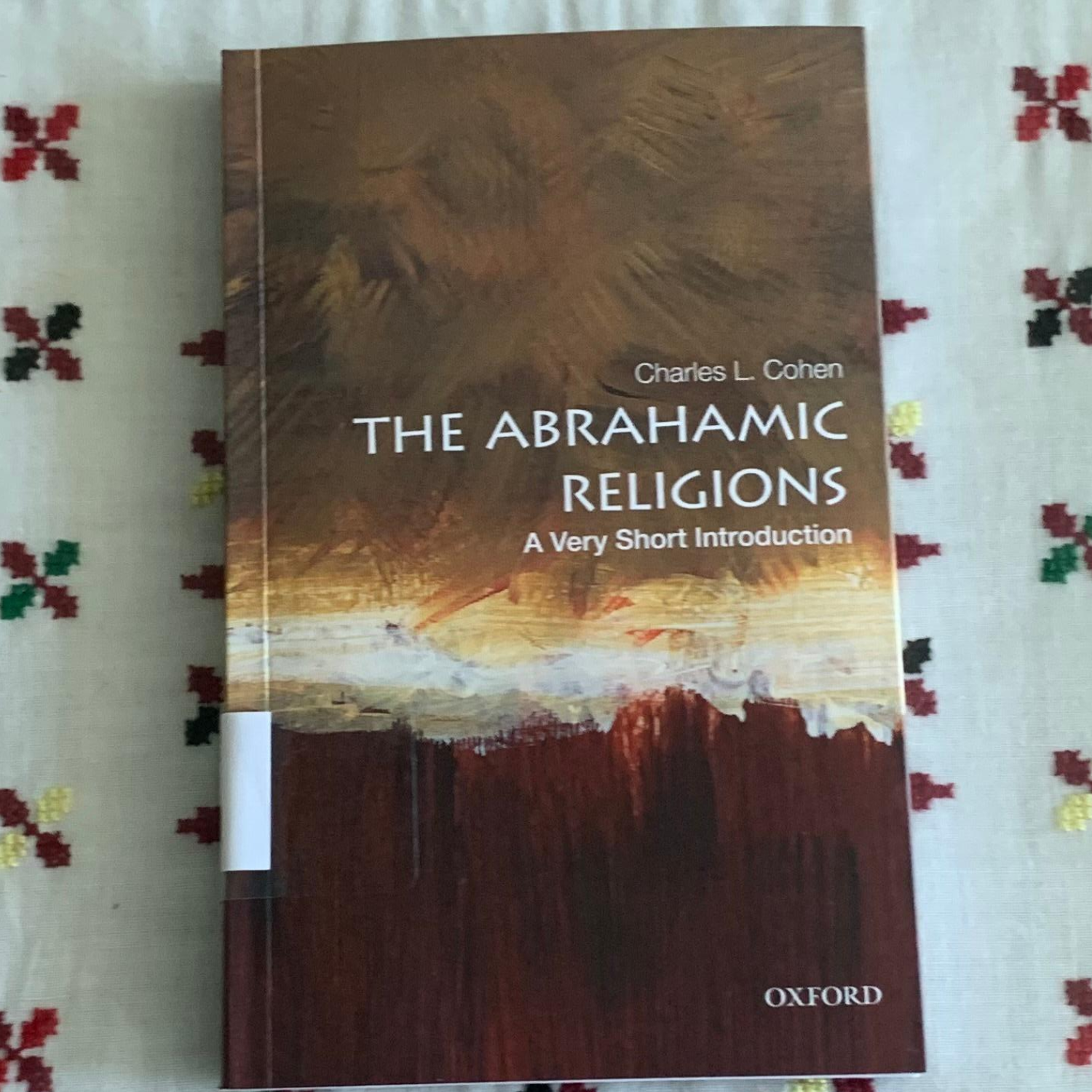

Charles L. Cohen, The Abrahamic Religions: A Very Short Introduction

UW-Madison historian Charles L. Cohen’s latest book, published in January, is part of the Oxford University Press Very Short Introductions series. Cohen is the director of the Lubar Institute for the Study of the Abrahamic Religions at Madison. In September, he will present a talk on the Abrahamic Traditions: A Story of Braided History.

The Abrahamic Religions: A Very Short Introduction, “brings these traditions together into a common narrative, lending much needed context to the story of Abraham and his descendants,” Professor Cohen said. Many Christians today are aware of their biblical connection to the Jewish tradition via Abraham, but see Islam as alien, other, a foreign, “oriental” tradition.

Professor Cohen, an emeritus professor of history at UW-Madison, is the author of God’s Caress: The Psychology of Puritan Religious Experience and has co-authored books and written articles on religious pluralism, theology and the secular liberal state, the impact of religion on colonial American politics, and Mormonism. In 1997, he took over the religious studies program at Madison, which up to that time had not been degree granting. Then he was asked by Chancellor John Wiley to develop an institute for the study of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Cohen became the founding director of the Lubar Institute.

“At the end of my career, I developed a course, which I call ‘braided histories,’” of these three great world religions, Professor Cohen said. “I’m more of a generalist today. If I had known where I would wind up, I would have studied Arabic in graduate school, but I didn’t need that for 17th century New England.”

The Very Short Introductions series by Oxford University Press was the subject of a 2017 New Yorker profile. It lists among its “very short introductions” the introduction to just about anything, from Abolitionism to Zionism and everything in between including Modern Latin American Literature, Homer, Tolstoy, Machiavelli, Modern War, Monasticism and Multi-culturalism, populism and Renaissance art, Socrates and Voltaire, teeth and telescopes. There’s even a Very Short Introduction to Nothing. Several are published each month, Cohen said.

A blurb on the series from Oxford University Press says it contains “hundreds of titles in almost every subject area. These pocket-sized books are the perfect way to get ahead in a new subject quickly. Our expert authors combine facts, analysis, perspective, new ideas, and enthusiasm to make interesting and challenging topics highly readable.”

Or, as Professor Cohen said, “They’re intended to be a sort of first book if you don’t know anything about something but you think you want to.”

Cohen’s very short introduction is “not longer than the others” at 35,000 words or 154 pages, including footnotes and a complete list of other Very Short Introductions by Oxford University Press. “In their format [4 inch by 6-inch page] “because it’s pretty small type, mine is 134 pages, the main text plus preface.”

Cohen’s intention for both his course braiding the three religions and his Very Short, was “I want . . . people, when they think of one of the traditions to automatically think of the others. I don’t want them to think about Islam or Christianity or Judaism by itself. The overarching intent is to make that connection, to not see these traditions as separate phenomena but to see that, throughout the course of time, they have been very much involved with each other.”

There was “no Christianity or Islam where I start, but that’s where the story starts. The first 4 chapters concentrate more on the origin in [Biblical] stories and the early interactions and then for the latter three chapters and epilogue, [when] all three are in the field, I can talk more about interactions between them.”

Cohen knows it will come as a surprise to some readers that each of the three religions traces its origin story back to Abraham. “Some people will link Judaism and Christianity but not Islam . . . I’m arguing against that position. A full appreciation of Judaism and Christianity in history must make a full appreciation of Islam in history as well,” Professor Cohen said. “My point is not to argue for one tradition over the other as a theological system. [But] we shouldn’t ipso facto cordon off Islam from Judaism and Christianity. There is too much that is shared among them and shared historically.”

So what is it that the three religions have in common at the most basic level? “The intrinsic similarity is that they all accept the one God as the only God,” Cohen said.

And all three trace their origins back to Ibrahim/Abraham. Jews see Abraham as the first patriarch, the first to teach the worship of the One God. For Christians, Abraham is the guarantor of the Covenant. They see themselves as Abraham’s heirs through a spiritual connection. Muslims regard Ibrahim as a prophet and a Muslim (one who submits to the One God).

“I think that overall the traditions recognize the fact that they are worshiping the same deity although they differ, of course, in terms of ritual and practice. The Christian argument with Judaism is not that the Jews have worshiped the wrong God, [but] in the Tanakh, the Hebrew Bible, there is a lot of concern that the people are worshiping false gods,” Professor Cohen said.

Christianity doesn’t make that argument against Judaism, “what it says is that Jews didn’t recognize that God was incarnated. You may know the one God but you don’t understand the one God correctly,” the professor said. “Islam will say Christians and Jews have gone astray from their own teachings . . . That is a different argument than the Quran is always making to the unbelievers or the idol worshipers.”

So what unites the traditions is their origin story, the mutual recognition that they worship the One God and their understanding of Abraham as a pivotal figure in that worship, although each tradition understands Abraham differently. “I’m always trying to go back and forth between things that are shared and things that are different,” Professor Cohen said. “I also try to say there is no single Judaism, no single Christianity, no single Islam. Their beliefs and practices, have constantly changed. And thinking of each of them as a monolith leads to stereotypes that can be both misleading and dangerous.”

Join Dr. Charles Cohen on September 10th at 7:00 pm as he discusses his book