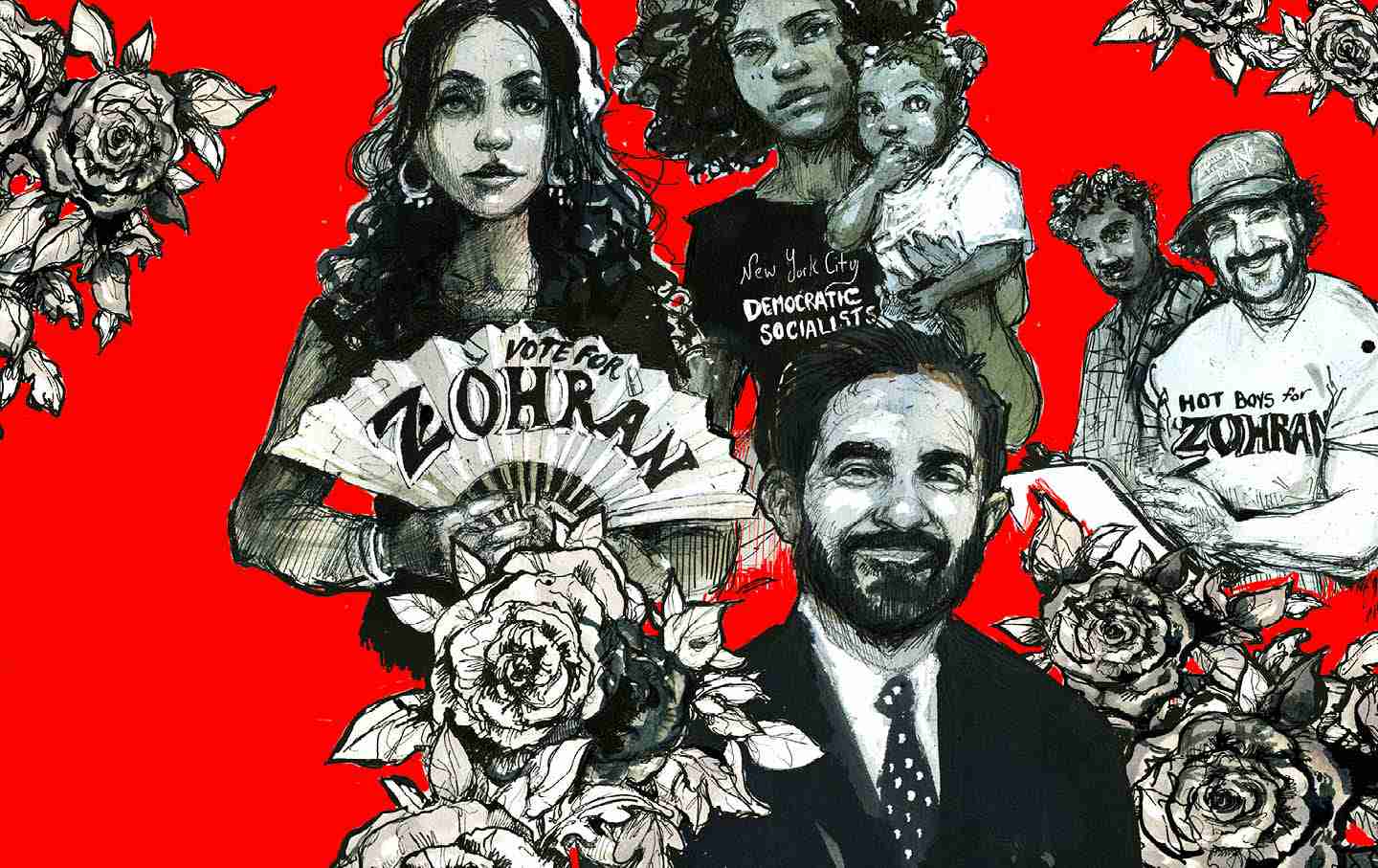

Illustration by Molly Crabapple

I started believing when Zohran gave his speech at the Church of the Village,” Kareem Elrefai told me. On June 24, the night it became clear that Zohran Mamdani would win the Democratic primary for mayor of New York City, Elrefai was beaming and sweating among the more than 100 Mamdani supporters packed into Boyfriend Co-op, a small bar in the Bushwick neighborhood of Brooklyn.

Two days later, on the phone, the conversation was quieter, but Elrefai was just as euphoric. A 28-year-old member of the New York City chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America and an elected leader of DSA’s National Political Committee, Elrefai explained that like so many others, he did not initially believe that Mamdani would win the primary. In fact, while NYC-DSA overwhelmingly endorsed Mamdani’s candidacy last October, the chapter’s members thought his path to victory was, at best, narrow.

Mamdani, after all, had little name recognition beyond his Assembly district in the Astoria neighborhood of Queens; he is also a Muslim in a city that had never elected one as mayor, a self-described democratic socialist, and a critic of Israel. At first he faced a crowded field that included the scandal-ridden incumbent, Eric Adams. The mayor would later drop out of the primary and opt to run as an independent, but by then former governor Andrew Cuomo—a party stalwart and scion of a New York political family—had also jumped into the race.

But on October 19, DSA members gathered at the Church of the Village in Manhattan to hear Mamdani speak, and it was there, Elrefai said, that he felt hope wash over him. Thinking back on that speech, Elrefai told me that he hadn’t been so moved since Bernie Sanders’s runs for president. It was Sanders’s 2016 campaign that inspired him to get involved in politics, and it was Sanders’s 2020 campaign that convinced him, on the day that Sanders dropped out of the race, to join DSA. Listening to Mamdani that evening, he recalled, “I just felt like, ‘Wait, we can do big things. We’re not just subject to the forces around us. We can be a force that affects the world.’”

That night at the after party, Elrefai gave Mamdani a hug and told him, “I didn’t believe. And now I believe. I see the vision.” Elrefai recounted that Mamdani replied, “We’re gonna win.”

Elrefai was on, as he calls it, “Team Let’s Build DSA With This.” Thanks to ranked-choice voting, an election method used by New York and a few dozen other cities, the risk of Mamdani being perceived as a spoiler was minimal. And win or lose, the young, charismatic state Assembly member could be an effective spokesperson for DSA.

According to Grace Mausser, a cochair of NYC-DSA, the biggest risk was that Mamdani would end up with a single-digit percentage of the vote, which would allow opponents to argue that “New Yorkers and Americans don’t want to vote for socialists.” But Mausser and others were confident that wouldn’t happen and that even if Mamdani lost, the organization would come out of it with greater capacity, new skills, more members, and better information. Just as previous losing campaigns had been opportunities to train up staff, build volunteer networks in new neighborhoods, and fill the organization’s district dossiers with data on electoral history, union density, and the number of residents who were DSA members, so too could this campaign—and on a much larger scale.

Three groups in particular, DSA wagered, could be activated by the campaign: left-wing activists, tenants of rent-stabilized apartments, and Muslims. While activists represent a small but influential demographic, more than 40 percent of New Yorkers live in roughly 1 million rent-stabilized units, and of the more than 350,000 Muslim New Yorkers who are registered to vote, only about 12 percent voted in the last mayoral election, making them a largely untapped voter base. Mausser, along with Tascha Van Auken (widely considered to be NYC-DSA’s field operations guru, now serving as Mamdani’s field director) and a few other chapter leaders, developed a “big swing” organizing strategy that they would use to build the campaign. Their goals included knocking on 1 million doors and recruiting hundreds of new members.

NYC-DSA surpassed its targets in less than six months. It helped the campaign recruit some 50,000 volunteers, of whom about 30,000 knocked on more than 1.6 million doors and made over 2.3 million calls. A quarter of the people who voted in the primary spoke to Mamdani canvassers at their doors. The chapter’s big swing delivered a momentous win: A little over an hour after the polls closed, Cuomo, the establishment favorite, conceded the race. As Mamdani declared on social media, “We rewrote the rulebook by talking to New Yorkers.”

Pundits touted the victory as a wakeup call for the Democratic Party, which had long ago lost touch with working-class demands and was failing to excite its base, much less inspire new voters. In the first round, Mamdani won nearly half a million votes, more than 7 percentage points ahead of Cuomo. By the time the ranked-choice results were tallied, that lead had stretched to 12 points. It was a landslide.

Most of the analysis focused on Mamdani’s youthful charm or his social media strategy and wondered whether the form of his campaign could be replicated without its content. Matt Bennett, of the centrist Democratic think tank Third Way, told the Associated Press, “The fact that Mamdani is young, charismatic, a great communicator—all of those things are to be emulated. His ideas are bad…. And his affiliation with [DSA] is very dangerous.”

Historically, Democratic primaries in New York City have determined the victor in the general elections, because the Republican Party has such a thin base here. But in this case, Cuomo and Adams are running as independents in November’s general election, and so DSA’s volunteer-driven political machine will continue to thump the streets. Now that Mamdani’s surprise primary victory has catapulted him to front-runner status, the city’s powerful real-estate industry, billionaire elite, and sundry other corporate interests are scrambling to cohere around a single candidate to oppose him. They will throw everything they have to stop a campaign that promises rent freezes, tax hikes on the rich, and a pro-union agenda. To lock in a win in November, DSA’s momentum will have to continue.

DSA’s Special Sauce

Much attention has been paid to mamdani’s social media presence during the campaign. His videos tapped into a young, online audience that the Democratic establishment has struggled to reach. In the videos—sometimes shot professionally, sometimes on Mamdani’s own phone—the candidate is always in motion, talking to everyday New Yorkers in common places: the subway, a bodega, a public park. But the unsung hero of Mamdani’s campaign is its field operations.

Sticking together: Designing a Mamdani sticker at a DSA- organized volunteer appreciation event in Queens.(Kara McCurdy / Courtesy of the Mamdani campaign)

Over the course of several years of campaigns—some won, some lost—DSA has assembled an electoral machine that is among the most powerful in New York City. DSA member Michael Carter told me, “It’s easier to explain and understand a viral video than it is a complex logistical machine distributed over four or five boroughs with 50,000 volunteers.”

Carter, like Elrefai and so many of DSA’s young leaders, got involved in politics through Sanders’s 2016 presidential run, leading a grassroots organization called Bushwick Berners and eventually going to work for the campaign. Carter later joined DSA, and in 2018 he became Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s second hire, leading fundraising and field operations as her deputy campaign manager.

That was an important year for NYC-DSA. After losing two elections in 2017, the chapter built on its electoral model during Ocasio-Cortez’s run for the US House and DSA member Julia Salazar’s run for the New York Senate.

What was unique about their approach, Carter explained, was their “field-first” strategy: “We basically said from the start, ‘Every other aspect of the campaign exists to serve the field operation.’” That included communications, fundraising, and compliance, and it flipped the script on typical campaigns—even for progressive candidates. Usually, Carter said, field workers serve as “the grunts of the campaign, coded as a working class.… If you go to a campaign wrap party, the people in suits are the comms people and the fundraising people. The people in T-shirts are the field organizers.”

Prioritizing field operations proved critical. Establishment campaigns like Cuomo’s gain tremendously from name recognition, but for insurgent campaigns, Carter said, “nobody knows your name yet, and you need to tell people the name.” It’s more effective to do that in person, he added: “It sticks in someone’s brain a lot longer if you meet a neighbor who tells you about it in a way that’s passionate, that shows that they care about it, than it is to just see a sign or a bodega poster or even a TV ad.”

This played out in Salazar’s campaign for the state Senate. The media hammered her with criticisms, scandals, and smears, but she won anyway. The reason, Carter argued, “was that Tascha Van Auken was running a hardcore field operation that bypassed the press, bypassed all that noise, and had individuals talking directly with their neighbors about these issues and about why Julia was going to fight for them more than the real-estate-backed incumbent.”

Almost 2,000 volunteers knocked on more than 120,000 doors and talked to some 10,000 voters, shattering records set by DSA’s previous canvassing operations. Ultimately, Salazar’s unabashedly pro-worker agenda, communicated by a mass field campaign, was more important to voters than the media- driven scandals.

Fast-forward to 2024. An electoral machine that had been formed in 2017 and then formalized, tweaked, and scaled up was put into motion for Mamdani’s campaign. But the massive number of people who are coming out to knock on doors is not simply the result of a well-honed logistical operation—it flows from DSA’s politics. As Carter put it: “If you gave the Cuomo campaign a list of 50,000 people who said they wanted to volunteer for them, they wouldn’t know what to do with it.” DSA’s electoral model cannot be replicated separately from its political orientation.

The ideology of democratic socialism matters, not least because these DSA volunteers are enthusiastic about what they’re doing. Videos of Cuomo’s paid canvassers affirming their own support for Mamdani drove that home during the primary campaign. “I was a bit hesitant, actually, to take this interview, because I didn’t want to be seen wearing this shirt,” one canvasser told a TikTok interviewer, looking down at his “Vote for Cuomo” campaign apparel. “I think he’s a morally reprehensible person.”

More to the point, the politics that Mamdani’s canvassers are committed to also resonates widely among New Yorkers. During a shift in the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn, a canvasser told me he’d heard about an 80-year-old woman who got so excited about Mamdani’s campaign that she took material to distribute to the rest of her building. Even if 50,000 canvassers could be found to knock on doors for a candidate with unpopular positions, it would be unlikely to turn an election. And while Mamdani is concentrating on class-based demands for an affordable city, the other issues that he is not shying away from—demanding an end to Israel’s war on Gaza, for instance—are also hugely popular among Democratic voters. During the primary, the Cuomo campaign’s panic about Mamdani’s criticisms of Israel arguably only made him more popular.

Those politics are also connected to an organization that is invested in building power among working people beyond election cycles, a commitment that has translated into a from-the-ground-up method of organizing. This is DSA’s “special sauce,” Mausser said: “We don’t gate-keep the skills you need to run a campaign.” The field operation gave ordinary New Yorkers who wanted to support Mamdani’s race an organization “to step into and gain new skills, and just do what needs to be done.” The “scarcity mindset,” in Mausser’s words, is a common ethos of traditional campaigns, “but it’s not a DSA one.”

DSA campaigns have four levels of field organizing. The first is the canvassers who knock on doors and make phone calls—“the bread and butter of what we’re doing,” Mausser said. Those canvassers who gain some experience and show an interest can easily become part of the second level as field leads, training new canvassers, managing the day-of logistics, and handling any issues that come up while a group goes door to door. In Mamdani’s primary campaign, more than 400 people stepped up to be field leads throughout the city. Naftali Ehrenkranz, a field lead in Crown Heights, told me that the campaign encouraged him to identify anyone who canvasses consistently and wants to step up. So while Ehrenkranz, also a DSA member, volunteered for that role in December, he helped bring in new field leads that could be deployed to other neighborhoods.

The third level consists of the field coordinators, who manage the leads, canvassing schedules, and campaign materials. Many of Mamdani’s field coordinators were volunteers who’d gained new skills for training, coordinating, and managing logistical operations along the way. Finally, the fourth level is made up of campaign staff. In more typical campaigns, Mausser explained, “you basically have staff and canvassers. So staff have to manage all the canvassing,” which makes the operation impossible to scale. “Even with a budget of $8 million,” she continued, “you can’t hire enough people to help 50,000 people canvass.”

Door-to-door service: Mamdani canvassers line up to get out the vote, campaign information in hand.(Melted Solids / Courtesy of the Mamdani campaign)

DSA as University of Left Power

These DSA operations are rooted in a politics that seeks to empower rather than lead from on high. Sanders popularized the idea with his slogan “Not me, us.” Mamdani echoed that sentiment in his June victory speech when he said, “This is not my victory; this is ours. It is the victory of the Bangladeshi auntie who knocked on door after door until her feet throbbed and her knuckles ached…children who called parents, strangers who care about those they will never meet.”

That includes people like Kareem Edmonds, who was born and raised in Brooklyn. After Donald Trump’s victory in 2024, Edmonds said, he frequently found himself doomscrolling and decided that the solution was to get involved in local politics. That realization coincided with his disgust at the idea of a Mayor Andrew Cuomo. Edmonds said he imagined a scenario in which Cuomo—who had resigned as governor in disgrace amid allegations that he’d sexually harassed at least 13 women and retaliated against those who accused him—would sweep the election, leaving New Yorkers “in another cycle of four years of crooked, crooked politics.” So Edmonds looked around and found Mamdani’s campaign. “As a struggling New Yorker myself, I did like what he had to say.”

Edmonds volunteered to canvass, and the result was transformational. “Having conversations with residents that were of my [African American] background, and them being so gracious to give me the space and time to yap in front of their doors for a good five, 10 minutes—that was a very uplifting feeling.” It felt, he said, “like communion with a complete stranger.” He signed up to canvass five more times through the course of the primary campaign. “Being a part of a coalition that wanted to do something is definitely one of the proudest things I can ever say I did.”

These types of experiences, which turned tens of thousands of people into communicators and organizers, were responsible for Mamdani’s victory and set him up as the front-runner in the November election. But they also made those thousands into active political participants for the long haul. When I asked Edmonds what was next for him politically, he said, “We have an obligation to sharpen our fangs” and get ready to fight for the policies of the campaign.

In this sense, likening NYC-DSA’s political operation to an electoral machine is only half the story. Álvaro López, a cochair of the chapter’s Electoral Working Group, calls it a “university of left power” made up of people who know how to “talk to working-class people about democratic socialism at the door and cohere a broader message to a level that excites thousands of people.”

DSA as Seed Money

Yet turning out hundreds of thousands of voters required an operation well beyond DSA’s capacity. In its previous efforts, smaller pools of voters could be reached by a campaign wholly operated by the organization. That was not possible in a citywide election with more than 3 million registered Democrats. López explained that in the primary, the “win number” for Mamdani—how many people needed to rank him No. 1 on the ballot—was in the six digits. (On Election Day, 469,642 New Yorkers ranked him as their first choice.) DSA could therefore be the backbone of the campaign, but not the entire structure. “We understood,” López said, that “even at six or seven thousand [DSA] members, all canvassing every day, that wouldn’t do it.”

But as Mausser put it, NYC-DSA provided the “seed money” for the volunteer base. In December 2024, the chapter held a town hall meeting with Mamdani. It was an invitation to join his campaign and become a field lead. More than 300 people attended, and from that group came the first cohort of leads. In just two weeks, they helped to bring in 400 more volunteers to kick off the first day of canvassing.

Among the leads were many DSA members who, like Ehrenkranz, had played similar roles in previous campaigns and could be trusted to jump in with little additional training. That base could be expanded exponentially. “We had a lot of experienced canvassers, members of [the] Steering [Committee] and [Electoral] Working Group,” López said, “but we knew we needed to replace ourselves quickly and do it like 10 times.” He estimated that while most of the campaign’s initial field leads were DSA members, by the end about 80 percent were from outside the organization.

The Mamdani campaign had its own separate apparatus, but despite the independence of the groups, consistent and seamless communication took place. Mausser and fellow NYC-DSA cochair Gustavo Gordillo met weekly with Mamdani and his campaign manager, Elle Bisgaard-Church. The chapter also formed task forces for fundraising, field operations, and communications, which met weekly with their counterparts in Mamdani’s campaign to coordinate and align work. Toward the end of the race, in a final get-out-the-vote push, Mausser recalled a meeting in which Bisgaard-Church requested help to secure as much youth turnout as possible. NYC-DSA responded at a moment’s notice with a text- and phone-banking effort by the organization’s youth wing, as well as an extensive tabling operation at several nightclubs in Bushwick and the Ridgewood neighborhood of Queens. “That was really well-received,” Mausser reported. “People were hype at like 1 am to talk about Zohran.”

Ultimately, Mamdani and DSA took a gamble to run for an office of national significance. They bet that the current political moment—one in which not only anger at Trump but also frustration at the inability of the Democratic Party establishment to effectively oppose him—would open the possibility of a left-liberal alliance. During the primary, this was borne out by a group of candidates and organizations who worked together to block Cuomo’s nomination. The campaign activated new canvassers and voters, drawing hundreds of thousands of young people and expanding the electorate way beyond its traditional boundaries. In so doing, the campaign has coalesced the city’s left forces around broad, populist economic demands and a resonant social justice message.

The lessons that DSA learned in the process of building a permanent grassroots campaign that popularizes and communicates a democratic socialist platform remain critical—and not just up to November. Wielding that popular power will be necessary to drive through Mamdani’s agenda if he occupies City Hall, as business, establishment, and policing interests will surely line up against him.

The campaign will also reverberate far beyond the city’s borders. New York City is at the center of the country’s political discourse. It’s no surprise that the primary election results immediately drew Trump’s wrath, but Mamdani will also attract left and progressive forces and individuals with political and economic expertise. Some will no doubt move to New York to help build the democratic socialist experiment here. Even more, Mamdani’s primary win will inspire others to replicate the NYC-DSA electoral machine in their own locales. It will help fill more city councils and state assemblies with socialists and motivate other DSA chapters to take big swings at executive offices. Broader progressive forces, too, from the Working Families Party to labor unions to community organizations, are playing significant roles in this election, and if this coalition continues to grow, it will provide a road map for beating back Trumpism and an ascendant right. With DSA’s electoral infrastructure, Mamdani has redrawn political lines in New York and, hopefully, beyond.