The Great Mosque of Djenne in central Mali, a Unesco World Heritage Site, is highlighted in Eric Broug’s latest book. AFP

n May 2020, Eric Broug locked himself away in the organ loft he uses as a study and embarked on his very own lockdown challenge. Rather than perfecting his banana bread, the Dutchman chose to sift through half a million photographs in the converted 19th-century chapel he lives in.

An internationally renowned expert in Islamic geometrical design, Broug’s practical books sell in six languages and have introduced the wonders of Islamic geometry to thousands of eager readers worldwide.

But in 2020, Broug’s publisher approached him with a request for something different, a new overview – not of details and patterns, but of Islamic architecture in its entirety.

Even with 25 years of experience, Broug’s new venture immediately placed him in a very illustrious tradition, as his publisher, Thames & Hudson, has already published several books on the subject by some of the world’s most eminent historians and academics.

Unperturbed, Broug embarked on his quest and set about carving a niche for himself with characteristic pragmatism and confidence.

“If you look at the general books available on Islamic art and architecture, it’s often both of them together – art and architecture – and then 65 per cent of the book is about art,” he tells The National.

“And it’s always the Middle East and North Africa, Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan and India, and they normally stop in the 16th century.”

Determined to make his book different, Broug committed to exploring Islamic architecture from a global perspective from the 7th century to the present.

“I thought this was an opportunity to put Islamic architecture in a global context by writing about buildings in sub-Saharan Africa, South-East Asia, Russia, North and Latin America, because you rarely see any discussion about those parts of the world,” he explains.

“I am also more interested in the stories that the architecture involves and the circumstances that led to its construction as they place it on a more human level.”

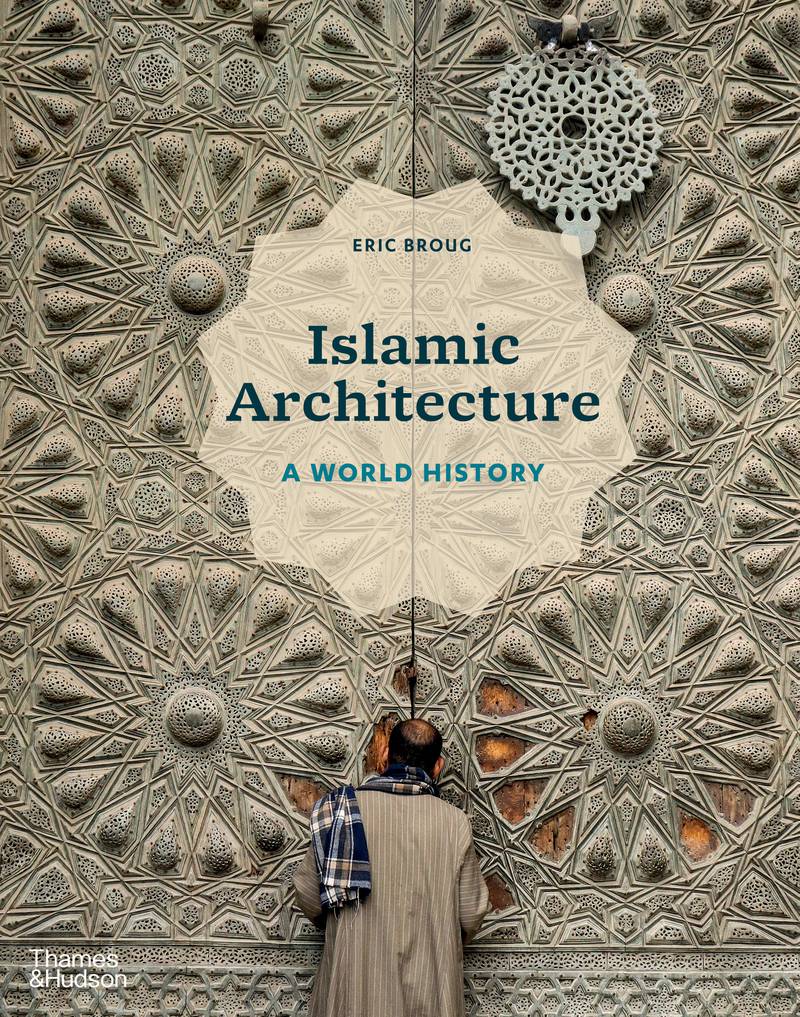

Broug’s quest for a global perspective and the very finest imagery took him on a 20-month-long trawl through the world’s commercial image archives, and when they didn’t suffice, he even ventured on to social media, which is where he found the arresting image that now graces the cover of his new book, Islamic Architecture: A World History.

Taken by an amateur photographer in Cairo, the photo shows a man in a traditional jalabiya stood before the massive doors of the Sultan Al Muayyad Sheikh Mosque (1421), which are clad in bronze panels bearing star patterns, a subject close to Broug’s heart.

“I saw it and immediately sent a message to the photographer saying, ‘Please tell me you took that with a proper camera’,” remembers Broug, beaming. “Luckily, it was high-resolution photo and it ended up on the cover.”

The long process of picture research, coupled with a desire to explore the global reach of Islamic architecture and its influence, took Broug on an odyssey from the religion’s heartlands in Arabia to Australia, Scandinavia, Canada and South America, and from traditional mosques and madrasas to Orientalist cigarette factories and contemporary museums.

The result is a kaleidoscopic image of a living and vibrant architectural tradition that spans space and time, from late antiquity to the present, that is the product of a living and thriving faith and culture that is as diverse in its influences and borrowings as it is in its admirers and adherents.

The research was a learning process for Broug who, like some architectural lepidopterists, still delights in the images he was able to collect. These include an interior shot of a humble mosque in a Rohingya village in Rakhine state, Myanmar, and a photograph of a crude mosque and minaret in rural Ethiopia, constructed by the region’s pastoralist Afar nomads. Constructed from little more than brushwood, the ramshackle mosque – a place of prayer and respite – sits on the edge of the world’s hottest landscape.

“Just think about those people travelling through the desert,” Broug says. “They’re not carrying sticks to keep themselves warm at night. They carried those sticks across a desert to build and maintain a mosque. That’s an amazing story.”

Rather than writing an academic tome that focuses on the development of architectural features and typologies, Broug has opted instead for an unashamedly visual approach that also includes architecture from other faiths and cultures that have sought inspiration from Islam.

Alongside acknowledged masterworks such as the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, Islamic Architecture: A World History also includes the penthouse suite at the Fairmont Hotel in San Francisco (1926), a favourite with celebrities such as John F Kennedy, Alfred Hitchcock and Mick Jagger that has a billiard room designed by the American historian of Persian art, Arthur Upham Pope.

The result is a book about architecture that has no room for plans, sections or even the many diagrams that Broug originally intended to include to show the reader how to draw their own domes, arches and geometric patterns at home.

This leaves the reader with a lightbox of architectural delights, accompanied by short essays and extended captions that shed just enough light to keep the pages turning while delivering a sugar rush of exquisite images accompanied by delicious anecdotes.

We learn, for example, that King Ludwig II of Bavaria installed a peacock throne in his Moorish Kiosk (1867), on which he would sit in an Ottoman costume while his courtiers served him tea “dressed as Muslims”, and that the French army built a replica of the Great Mosque of Djenne on the Cote d’Azur in 1930 – complete with concrete termite mounds – as a community centre for its West African colonial troops.

At the end of his book, Broug also includes a chapter on women in Islamic architecture that features potted biographies of women whose charity, power and patronage produced some of Islam’s greatest architectural marvel, such as Zubayda (762-831), wife of Abbasid caliph Harun Al Rashid, whose concern for pilgrims making the 1400-kilometre journey from Kufa in Iraq to Makkah resulted in a string of wells, water tanks, pavements and rest houses that still bear her name.

It is here, however, that Broug’s book comes unstuck, as his welcome inclusion of women in the story of Islamic architecture ends in the 17th century and fails to take the contribution of contemporary female architects into account.

Zaha Hadid’s work is included – her campus for the The King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Centre in Riyadh features prominently – but there is no room for Bangladeshi architect Marina Tabassum, whose simple and serene Bait Ur Rouf mosque won the 2016 Aga Khan Award for Architecture; Pakistan’s first female architect Yasmeen Lari, who was awarded the UK’s RIBA Gold Medal in 2023; or for Sumaya Dabbagh, one of the few Saudi female architects of her generation and one of only a handful to lead her own practice in the Gulf.

But to criticise such a personal selection of buildings and images for its omissions feels churlish: Broug’s book claims to be nothing more than a personally curated source book. Judged purely on those terms, it is a success that will undoubtedly delight the general reader by providing a sumptuous primer to one of humanity’s most enduring and dynamic artistic traditions.