Photos courtesy of Andron Lane

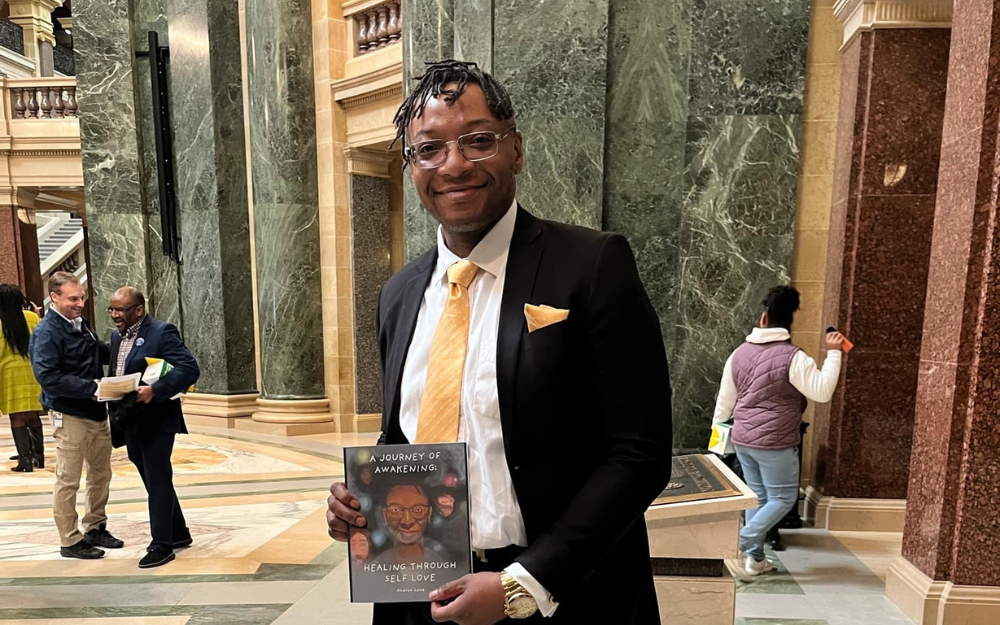

Milwaukee entrepreneur Andron Lane, Sr. poses at the Wisconsin State Capitol, holding his 2024 book, A Journey of Awakening: Healing Through Self-Love.

For Andron Lane of Milwaukee, 2024 was a very good year.

Accolades and awards for his leadership and community service rolled in—Project Return’s Elijah O’Neal Award of Excellence, North Avenue 3B’s Community Engagement Award and Fathers Making Progress’ “Comeback Dad of the Year.”

Business education company 24 HR Entrepreneur flew Lane to Houston to receive its national Award of Excellence for his consulting company, A.Q.L.S.

Maurice “Moe” Mitchell, activist, rapper, musician and national director of the Working Families Party, who travels across the country filming “Conversations with Black Men,” came to Milwaukee to interview Lane. Mitchell called the episode “one of the most crucial” recorded in 2024. (See the full conversation.)

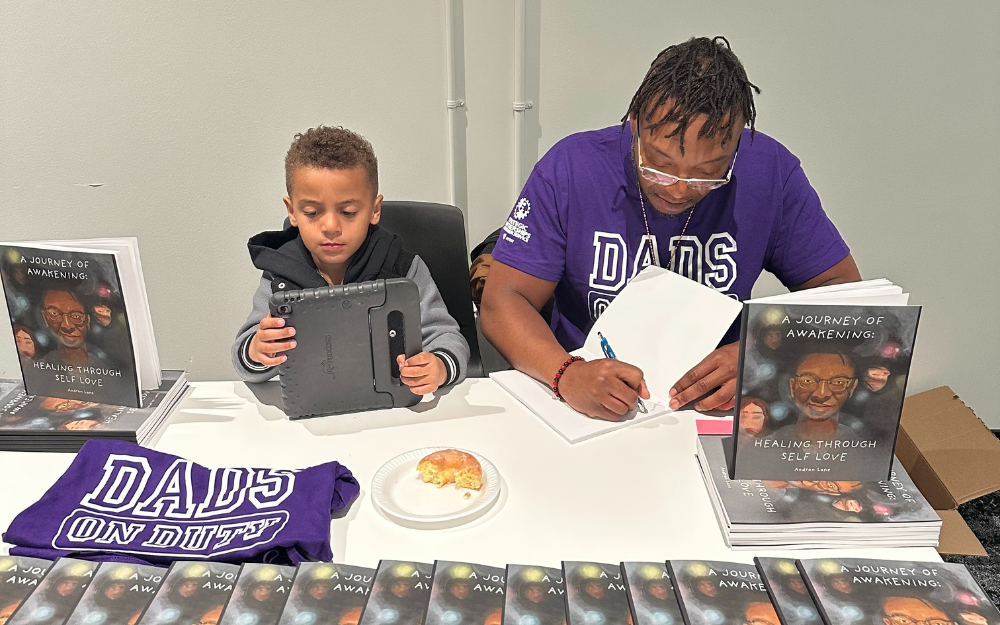

Lane published his first book—A Journey of Awakening: Healing Through Self Love. More than 200 turned out on a snowy December night for the book launch at Milwaukee County’s Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Community Center.

Probably most significant—at 42, for the first time since he was 18, he got “off paper,” justice system lingo for no longer being under the supervision of the Department of Corrections. Lane had spent 18 years in confinement and eight under community supervision.

“I got off parole Jan. 15, 2024,” Lane told Wisconsin Muslim Journal at an interview last month at Fruition MKE, a new creative workspace and café in Milwaukee’s Concordia Neighborhood that, like Lane, blossomed in 2024. “That was the first time in all those years I was not either on parole or in prison,” he said.

And being “off paper” meant the State of Wisconsin restored his voting rights.

“Voting became a metaphor for my journey of healing,” Lane wrote. “Just as I had the freedom to step into a booth and mark a ballot, I also had the freedom to step into my own life, to claim my space and advocate not only for myself but for others who had been disenfranchised, forgotten or silenced … it was about choosing to see myself differently.”

In several interviews with WMJ, Lane, now 44, described his journey to address personal trauma, heal and thrive. That journey taught him how to help others, for which he is now widely recognized.

From the beginning

Lane led the WMJ reporter out a side door of the café to a table in a hallway where we’d have the first of several conversations over the next month. To stay inside would mean risking constant interruptions from Lane’s friends and acquaintances who frequent Fruition MKE.

Dressed in a navy and white tracksuit and wearing white athletic shoes, he looks the part of the self-proclaimed “fitness practitioner” he is. As we had met only briefly at his book launch, I told him I was there to hear as much of his story as he was willing to share.

It poured out.

Andron Lane, Sr. frequents Fruition MKE, a new creative workspace and café in Milwaukee’s Concordia Neighborhood, co-founded by Tiffany Miller.

“Telling about my journey is a way for me to advocate for myself and let people around me understand what I am going through,” he explained softly in the slow, smooth cadence of a mindfulness instructor, which he also is.

“To start, I was born here in Milwaukee.

“I’d just like to point out some things in my life,” he continued. “I grew up in a single-parent household. My father was absent. I’ve seen him exactly 17 times.”

During the years of Lane’s incarceration, his mother “was dealing with her own struggles,” he said. “I think she saw me five times the whole time I was in prison.” Now, as an adult, Lane realizes “she might not have had the money to get there,” but at the time, he said, “As a kid, am thinking, ‘You don’t love me.’

“I didn’t know what joy feels like. I didn’t understand happiness. I stripped myself away from it. I didn’t want to have anything that reminded me of home, of happiness and family.”

Incarcerated

“I went to jail for the first time at 13, to a detention center here in Milwaukee, for stealing a bike.

“I think I next went to Wales (the now-closed Ethan Allen School for Boys) for armed robbery. Me and my friend had a fight with somebody and we ran off with his shoes, yelling, ‘We got your shoes,’ like bragging rights. His mother called the police and they gave us jail time for armed robbery.”

“Were you armed?” I asked.

“No. They said it was an armed robbery because we had sticks.

Lane received “some of the worst treatment I ever experienced” in facilities for juveniles. He described sitting alone in small, dark rooms for hours or being in segregated rooms wearing suicide suits, wrapped vests held by Velcro straps, and the use of riot gas and pepper spray to restrain youth.

Shot

At 19, a gunshot wound led to Lane’s confinement in RYOCF (Racine Youthful Offender Correctional Facility), where males from 18 – 24 are incarcerated.

“I was shooting dice in a back alley near 24th and Center. Some guys ran up on us and robbed us. In the process, I was shot twice in the back. I ran home, full of adrenaline and not aware I was shot,” he said. “Close to home, I was walking down an alley and I saw some of the neighborhood ladies.

“’Andron, why are you sweating? What’s going on?’

“I told them, ‘I don’t know. I think I’m shot.’

“’Turn around. Your back is bleeding. Call 9-1-1!’

“I’m like, ‘Don’t worry about it.’ I wanted revenge, retaliation. My cousin had me hold his gun for him. I went downstairs to get it. When I came back upstairs, I passed out on the front porch.”

Andron Lane (left) voted for the first time in 2024, after Wisconsin reinstated his voting rights. His friend and co-worker Gabi Hart (right) also voted that day and celebrated with Lane.

Andron woke up in the hospital to find he was charged with two years of probation for felony possession of a firearm since he had prior convictions.

Further charges and a plea bargain that went bad brought him more time in confinement.

“Two months after I got there, a guard committed suicide in the tower. Nine months later, another guard shot himself in the parking lot. All this stuff was happening.

“I remember, I called my mama and I was telling her, ‘You need to get me out of here because they are killing themselves. I know they are going to kill me!’

“I didn’t know how I was going to do the time and, even now, when people ask me how I made it through so much time, my answer is, ‘I don’t know.’”

Becoming a Muslim

While in prison, Lane met a few Muslims. “I saw that those following Islam seemed to be at peace,” he said.

He confessed his initial motives for considering Islam were not the best. “Islam became an easy way to hide the pain. We weren’t celebrating holidays (like Christmas and Easter). We didn’t have pictures of things that reminded you of home and happiness. We did not act emotional about things. It was easy to hide under that.

Andron Lane (left) is someone who serves others, said his friend Samantha Collier (right).

“I knew more about faking Islam than understanding it. I knew the greetings but I didn’t know my prayers.”

Making Muslim friends in prison who shared books and reading material with Lane put him on the path to Islam. It began in 2004, when he was in a maximum-security facility in Green Bay. In mid-2004, he was moved to a medium-security facility in Red Granite. “My cellmate happened to be another Muslim. He kept telling me to come to jummah prayer. I’m like, ‘Yeah,’ but I just sat there gambling. He never judged me.

“Then another Muslim brother who is now a really good friend of mine moved down the hall. What brought me to Br. Musab is that every time I walked downstairs to the dayroom, he would be sitting in the back reading. So, I would sit in the back and read. Then he asked me to go with him to jummah. I’d sit in back and listen to the conversation.”

In a recent Zoom interview, Br. Musab said, “I was just thinking the other day about how Andron hung out with me despite knowing I wasn’t into a lot of things that went on in prison. Andron was looking for more. He was looking for better ways to live, better ways to deal with situations. He would ask me questions all the time.”

The more Lane went to Friday prayers, the more Br. Musab encouraged him to take his shahada, the declaration of faith in Islam. “To be honest, I think I still held the same pretense I had before,” Lane confessed.

Lane took his shahada in 2005, and felt sincere about converting, but didn’t feel like he was really a practicing Muslim for another decade.

Bad news from home “triggered me to shut down,” he said. “It broke me. Bad things were happening back-to-back. There wasn’t any training and I didn’t have a healthy understanding of what it looks like to deal with (all that bad news). I tried to read the Qu’ran and the books. I couldn’t. I was waking up with tears. I just couldn’t stop crying.”

In 2006, Lane went home on parole but in 2008, he “did an armed robbery and went back to prison,” he said.

“The judge gave me two years to run consecutively with the 10 years I had left on paper. Just the armed robbery alone was 25 years and there was also a possession charge. He said I was over-sentenced as a child, and they did nothing to prepare me.

“This mercy gave me a chance to really think. I realized I can’t do this anymore. I said to myself, ‘I’ve tried everything except getting a job and just living.’”

He did his time—10 years, eight months and 11 days. By the end, he was fasting during Ramadan and practicing his new faith, he said. He had also moved to minimum security, “going out for work release, reading and watching a lot of PBS.”

“I remember when I came home—Aug. 28, 2018.”

Building a life

At 6 foot 3, Lane stood a head taller than any other parent by the colorful play equipment at the new Wick Field Park playground in Milwaukee on the first Sunday in July.

His son, 5-year-old Andron Lane, Jr. looks like his dad—tall for his age with a slim build, caramel complexion and light brown curls sitting on top of his head.

Andron Q. Lane, Jr. (left) accompanied his father Andron Q. Lane, Sr (right)., as Andron Sr. signed copies of his new book.

With a watchful eye on Junior, Andron Sr. glanced as I scanned photos on my phone of Lane holding numerous awards, helpfully identifying each one. “I never anticipated getting these awards. I never tried to. They blew me away,” he said.

Several were for community service in Milwaukee. Another recognized the work he has done through the consulting company he founded in 2020, A.Q.L.S(an acronym for Another Quality Lifestyle and also his initials, Andron Quintell Lane, Sr.).

Project Return’s Elijah O’Neill Award of Excellence is given to an outstanding returning citizen, back in the community after serving time. “It was the first time they gave it to somebody who had been home just five years,” he said.

And finally, there’s one for being a great father. “Having my son, my pride and joy, brings me so many emotional feelings, so much happiness and joy that had been stripped away from me,” Lane said.

From there to here

“How did you get from where you were to where you are now?” I asked. “Was there a turning point?”

“I can’t say there was a turning point,” Lane responded.

Andron Lane, Jr. joined his father at the Fathers Making Progress 2024 Gala, where Andron, Sr. received the “Comeback Dad of the Year Award.

Rather, he started slowly, trying to learn how to do things that had never been modeled for him, like how to be a Black man, a father and a citizen. As he learned, he gained confidence and felt a belief in himself growing.

When he was in RYOCF, acclaimed poet and author Dasha Kelly did a poetry workshop. “I went to different classes because I didn’t want to be in my cell,” Lane confessed. He had been writing poetry since he was 12 years old and continued while in juvenile detention. But it was Kelly’s workshop that reignited the flame.

“That’s when I got to do a lot of my writing and I learned how cool it can be. It inspired me to do more writing and more dreaming.”

In a conversation Monday, Kelly said she and Lane have stayed in touch since he returned to the community.

“We really connected at that point because now it’s how do I show up?” He continued participating in her writing workshops and sometimes helped facilitate.

“A lot of things happen on paper we dream about; it takes a whole lot of healing and fortitude to actually walk through it. He’s had a lot of things to figure out. I’ve been so inspired by Andron’s walk and how committed he is to doing better today than yesterday,” she added.

And Islam brings peace, Lane said.

But there have been setbacks.

“I went through a real bad belt in about 2022,” he recalled.

“What does that mean?”

“I was drinking too much. I didn’t know where to live. And all these traumas and struggles from my past kept popping up and I didn’t know how to deal with them successfully,” Lane said.

“I was helping with a workshop when a young girl got up and talked about how her uncle touched her. Something in me broke. I thought, ‘That’s what happened to me.’

“For the first time in my life, I realized why I was crying at night—because I was molested as a child and I didn’t know it. I had blocked it out.”

That’s when Lane needed to find out what a thriver after sexual assault looked like. He did personal introspection. He talked with others. He went to therapy.

“I’m still surviving it. I’m still learning from it. I’m learning how to be happy. I’m still looking to be a better me.

“But I can say this—I’m learning I’m not only just a survivor but I’m thriving. My life experiences have given me a chance to advocate for advocacy.”

Lane is building a career and a life of advocating for himself and others. A master of bringing people together, he has organized forums in his former position as the Milwaukee Turner Community Wellness Coordinator, through his consulting firm A.Q.L.S. and as a community leader and collaborator with government agencies and community organizations. He even turned his book launch into a panel of community leaders to share their expertise with the community.

He’s worked on his education and credentials, earning certificates in peer support, mental health first aid and as a restorative justice circle facilitator. He’s set his sights on a university degree.

In a recent Zoom interview, his friend Samantha Collier, founder of TeamTeal365, which supports survivors of sexual violence, said, “One thing about Andron, he’s a man of serving. He enjoys helping the community, serving the community.

“I myself serve an amazing God. Andron feels the same way around his own personal journey with God,” she said.

Lane recently gave notice at Milwaukee Turners to fully engage as an entrepreneur. “It’s time to bet on me,” he explained.

“I am building a legacy for my son to say, ‘You know what, my daddy, this man, looked for tools to assist others, but also to assist himself.’

“I tell people I am the consumer. I’m struggling with rent. I’m struggling with understanding, child support, and healthy relationships. I’m that same person who will use these resources we are building and the understanding we are gaining.”