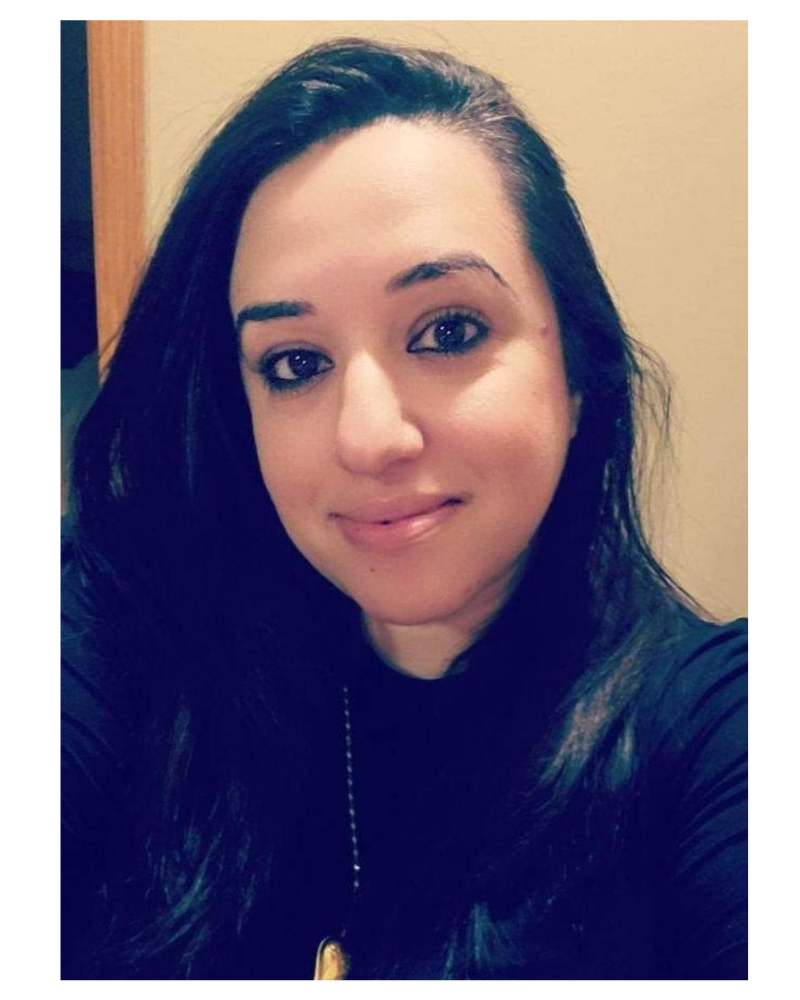

The charitable version of a mobile response team, Hanan Refugee Relief Group has gained a reputation for working at the ground level to quickly respond to community needs. Sheila Badwan, 36 and the mother of two, founded Hanan in Milwaukee in 2017. But even before a formal Hanan organization existed in Wisconsin, Badwan was working with refugees locally.

“It was all very grassroots,” said Tables Across Borders founder Kai Mishlove. “I was living on the North Shore, and when I came across an estate sale, I would use some of the items for refugee families I knew, and then I would ask Sheila if she needed any of the things.”

Badwan and Mishlove continue to work together on refugee issues but with more organizational support. Mishlove’s refugee work eventually led her to the position of program coordinator for refugee services at Aurora Walker’s Point Community Clinic.

Hanan, Mishlove said, has been “extremely generous [with] donations and support needed for local refugee families,” and, she said, “the food they donate to families is culturally appropriate, which is not always the case at food pantries.”

Hanan Refugee Relief Group was started in 2016 in Greenville by Dr. Ruba Sarsour, its current president. Sheila’s sister, Samar Badwan, currently serves as its vice president. Sheila Badwan is the group’s secretary.

Hanan’s mission, according to its Web site, is to “transition refugees into contributing members of their host communities by providing long-term solutions, such as housing, labor opportunities, and medical relief.” It is a self-described “humanitarian” organization with no formal religious ties, though many of its leaders and volunteers are Muslim.

And, unlike most non-profits,100% of the money Hanan raises through donations and its annual fundraiser is dedicated to helping refugees. According to bizfluent.com, most non-profits devote up to 40% of the money they raise to “administrative costs”: employee salaries, building maintenance, utilities, supplies, and marketing.

Hanan has no employees. Board members, volunteers, and outside donations supply the funds for its relief work. However, Badwan said the group is now involved in carefully documenting the aid it supplies in order to apply for grants in the future.

“We are very small,” Badwan said, and “we aim to stay small. When we started, we weren’t really planning on being even as big as we are now. We don’t want to be one of these million dollar charities.”

Badwan admitted that “when you’re all-volunteer, it’s hard to keep people on.” But Hanan has found a group of about 15 women and 5 men “who are really committed,” she said. “Whenever we decide to do something, we just kind of talk about what is really needed. We use the resources in the area.” Badwan often works in partnership with other organizations like UMOS, Muslim Community Health Center, local mosques, Milwaukee Muslim Women’s Coalition, and ISM.

Hanan recently partnered with Our Peaceful Home, MMWC’s anti-domestic violence program, “providing furniture, household items, and gift cards for single mothers with kids,” Badwan said.

Janan Najeeb, president of Milwaukee Muslim Women’s Coalition and director of the Our Peaceful Home Project spoke in glowing terms of Badwan and Hanan. “What I find especially appealing is how they view each refugee as deserving of dignity. They will only offer them items that are brand new or like new. They think, What if I was in that situation? Hanan replaces many used items in poor condition that were given by resettlement agencies with new items. They are not receiving any government money, but they are doing it because it is the right thing to do. I joke that Sheila is the energizer bunny. We will make a request for something for our single moms, and it seems we barely put down the phone and she is there with her van!”

And, for a small organization, Hanan has a long reach. The group has partnered with international relief groups to rebuild houses in Gaza and other areas where there has been widespread destruction. One of Badwan’s volunteers has committed himself “just for our international projects in the Gaza Strip and Jordan.”

Hanan has sponsored clothing drives and toy drives to help families devastated by the Syrian civil war. Badwan said that 6 churches in Sheboygan “collected brand new toys for kids in Syria,” enough to fill 40 shipping containers.

The containers were provided by Salvatorian Mission Warehouse in New Holstein, Wisconsin, where donated relief goods are sent around the world. “We pay the fees for the container and they ship it for us,” Badwan said.

Internationally, Hanan does 3 to 4 large projects a year, Badwan said. “We are registered through the government in Palestine,” she said. But “in order for us to work, how we do our projects, we contract with large charities like Rahma Worldwide and United Palestinian Appeal.” Hanan supplies the money for the project, including a 5% fee to the larger aid organization. Hanan’s projects are then implemented by that organization. “But we also have a Hanan team member on the ground watching over the project,” Badwan said.

In partnership with UPA, a kidney dialysis center for Beirut, Lebanon is in the planning stages.

Badwan was born in Raleigh, NC but grew up in Greenville and attended East Carolina University. Her husband Yahia is from Beitin, Palestine, the home base of Sheila’s family. The couple moved to the Milwaukee area in 2006. Badwan’s husband operates a US Cellular store. Badwan, who says she has “always worked,” is currently a substitute teacher in the Franklin school district.

One of the things that first energized Badwan about helping refugees here was the large number of Syrian, Somali, and Rohingya refugees coming into Milwaukee who she felt were not well served by larger, well-established relief agencies.

“These agencies get tons of money from the government to settle families,” Badwan said. “[And] you really see the little holes that happen in how these families get treated, how they’re settled.”

Badwan spoke about a Syrian family with 11 children who were “placed in a condemned home. There was mold, no furniture. It was horrible.” When Badwan spoke to the organization about it, “it was like, this is not your problem, leave them alone.”

But, she said, “refugees have rights.” Refugees “get resettled by agencies, but [the agencies] expect them in 3 months to learn everything, and then the next family comes in.” And three months isn’t usually long enough to learn the ropes in a new country with a new language, customs, and laws. So that’s where Hanan steps in.

Hanan helps “with everyday things,” Badwan said. “We taught someone how to drive, how to get a license. We brought in some English teachers and taught ESL for three months. We did a homeless drive last year and were able to distribute 400 tote bags with basic necessities for the winter.” Hanan also sponsors regular food drives and school supplies drives.

Currently, due to Trump administration travel bans and moratoriums on refugees, “there are not a lot of refugees coming in,” Badwan said. “They are trickling in, and the numbers are small and scattered. There are more Christian refugees because of the Muslim ban.” However, the coronavirus pandemic has been “really tough” on those who are already here. “It’s a very challenging time. You can definitely feel a lot of stress and anxiety among the refugee families.”

Hanan has been supplying food boxes to those furloughed from their jobs or who have lost jobs and has also provided education on the virus with help from translators connected through Mishlove.

A large percentage of refugees helped by Hanan have been Syrian, Badwan said, “but we do have other ethnicities on board,” including Congolese and Burmese Karen. However, said Badwan, “We do have a large Arabic speaking team,” which enables Hanan to supply its volunteers to other agencies when translation help is needed.

MMWC board member Sausan Naji, a Hanan volunteer, said the group focuses on both “immediate and long term needs.” The group is effective, she said via email, because “individuals and other nonprofits . . . realize they can count on us to get things done and be there for anyone in need.” And, Naji said, the fact that expenses, “including administrative and travel, are paid for by the volunteers themselves” builds trust with the community.