In 1990, I was asked to present a paper on great Muslim scholars of Spain at an international convention of the Islamic Medical Association of North America (IMANA). I must confess to having little knowledge about the great Muslim scholars of the medieval years at that time. After extensive research to help prepare for my lecture, there seemed to be no mention in the history books or books of science and medicine of the contributions made by Muslim scientists, philosophers, and scholars of the medieval period to world civilization.

Historians commonly refer to the period between 500–1200 C.E. as the “dark Ages,” denoting a time of intellectual darkness and barbarity in Europe. This label is wrongly applied universally – and clearly shows a lack of recognition for the scientific and scholarly work that was contemporaneously being pioneered in the Middle East and Muslim Spain.

The scholarly work of outstanding Muslim scientists such as Al-Kindi, Ibn Sina, Al-Razi, Zahrawi, Ibn Al-Haytham or Ibn Khaldoon (7th-15thCE) was rarely acknowledged in major publications of medical and scientific works in the West. This meant that graduate and post-graduate students, Muslims and non-Muslims had no knowledge of contributions made by Muslim scholars between the 7th and 15th centuries.

Unfortunately, this suppression has continued. Most books and articles on the history of medicine and the sciences outline the contribution of Greek and Roman scientists which is usually followed by scientific progress since the Renaissance. Students are taught that Christian European scientists made all the scientific advances after the original Greek contributions.

Morowitz, a historian, described this phenomenon of concealment as “History’s Black Hole.” “This is [a] myth that gives a distorted view by giving the impression that [the] Renaissance arose Phoenix-like from ashes, smoldering for a millennium of the classical age of Greece and Rome.” [Morowitz 1992].

So how did we challenge this centuries-old conspiracy of silence?

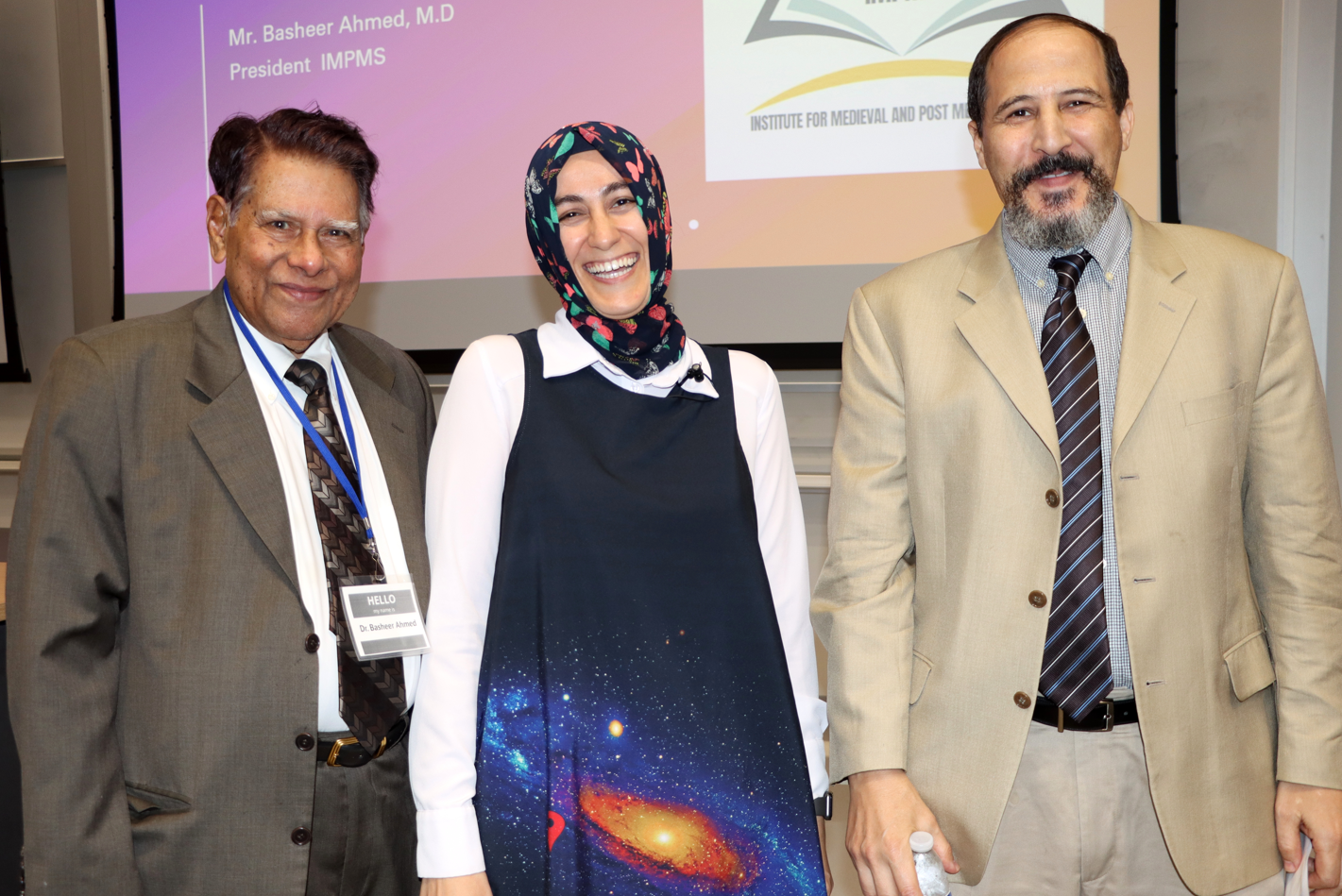

In 2001, Ambassador Syed Ahsani, Dr. Yusuf Zia Kavacki, and I met Professor Dilnawaz Siddiqui, past president of the Association of Muslim Social Scientists (AMSS), who visited Dallas to explore the possibility of organizing regional conferences for AMSS.

It was this meeting of minds that led to the creation of the Institute of Medieval and Post Medieval studies (IMPMS.)

The underlying goal of IMPMS is to help generate a climate of mutual understanding and respect among people, especially between Muslims and those of other faiths and cultures. By exploring Islam’s historical contribution to discovery and progress we can chip away at notions of a clash of Islamic and Western civilizations.

However, as a Muslim, I am embarrassed to admit that in the last five hundred years, our contributions in the field of science and technological innovation have not kept pace with the legacy we were given. Worse, we have failed to preserve the treasures left behind by our forefathers and past scholars. It’s estimated that about 60% of their valuable work in every field spanning the sciences and technology has been lost.

In fact, it’s been European and American historians who have accessed the translations of scholarly work by Muslims and started writing about their scientific contributions in the medieval era in the late 19th and 20th centuries. This has meant new Muslim generations have lost this knowledge and in fact, grew up with a sense of inferiority – assuming that Western scholars are the only preceptors of all science and technology. This is what made the Muslim world incapable of serious thinking, research, analytical work and creative thinking.

One of the aims of IMPMS is to motivate Muslim youth to follow in the footsteps of their able forefathers and passionately pursue the arts, humanities, science, and technology.

Since 2001, IMPMS has held major conferences inviting international speakers to address large audiences supporting our mission and share the rise and fall of the Muslim civilization, in order to restore Muslims’ intellectual tradition of the medieval years.

Here in Texas, we took an important step in 2018 by collaborating with Discover STEM, an academy devoted to training the young to become innovators and scientists. Its CEO, Faizan Mirza, is on the IMPMS Board and has added another valuable dimension to our institution.

Our collaborations in recent years have resulted in joint seminars attended by hundreds of students, educators, physicians, and professionals.

In 2020, our guest speaker was Dr. Hashima Hussain, an astrophysicist from NASA who has been working on the James Webb Telescope and in 2022, Dr. Mutlu Pakdil, an astrophysicist who became the first Muslim woman to have a galaxy name after her, was our keynote speaker. These speakers were a great source of inspiration for our young boys and girls.

Despite these positive steps, as Muslims, we still need to ask the question of why Muslim civilization, after having thrown such light on the world, suddenly became extinguished; why this torch has not been relit since; and why some of the Muslim world still remains buried in profound darkness.

I hope my book, “Rise and Fall of Muslim Civilization- Hope for the Future” sheds light on where we went wrong and how we can get back on track. It also includes papers published by other esteemed colleagues from IMPMS, and collectively we offer an outline of how to remedy and train students to become future scientists.