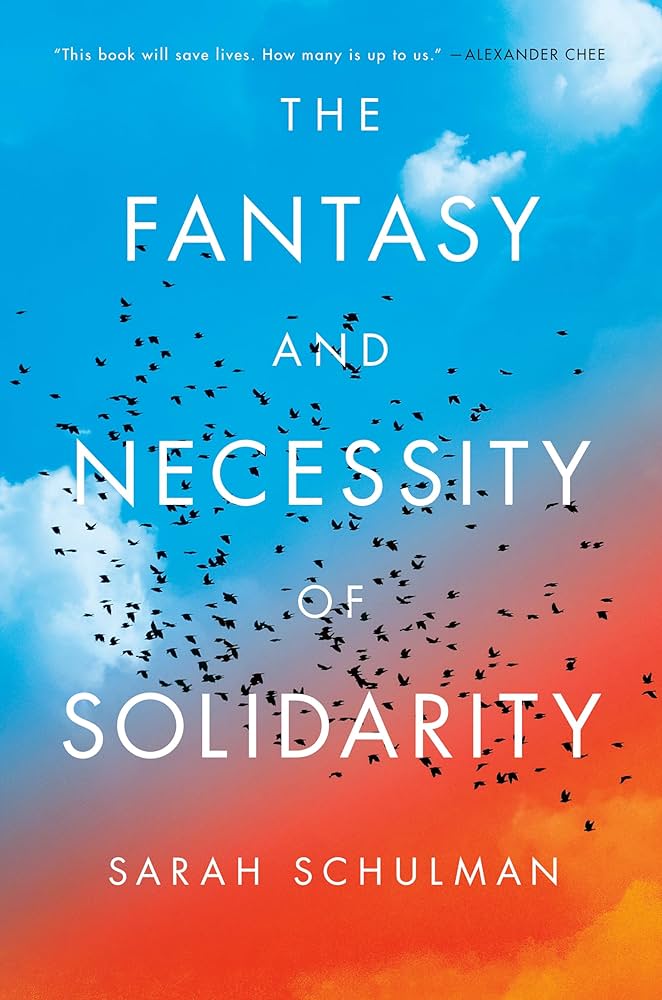

THE FANTASY AND NECESSITY OF SOLIDARITY

by Sarah Schulman

320 pp. Penguin Random House $30

Author Sarah Schulman’s latest book, The Fantasy and Necessity of Solidarity, brings together eclectic historical movements, moments, and cultural workers and texts, to push readers to contemplate how one acts in solidarity. This is especially prescient at this particular moment as her book was composed in the midst of the ongoing Israeli-American genocide in Gaza. It explores the various ways in which activists are responding to state actors or the institutions that give license to those states committing war crimes. But she also confronts readers with essential realities such as, “in our age of globalized capital and its manifestations in government, we can’t stand up to conglomerated power by ourselves” (12). Although we may not need the reminder, Schulman situates us “within complex structures of illegitimate power that are both entrenched and invisible” (12). Such structures of political, social, economic, and cultural power are also intertwined and consolidated into fewer and fewer hands (13). So, what’s an activist to do?

Perhaps the volume’s opening epigraph is a good place to start. The quotation of Ghadir Shafie, a Palestinian queer activist, poses, “‘Ask what you can do, not what you can lose.’” It’s a kind of mantra that resonates through Schulman’s book as she highlights aspects of activist movements across the twentieth century. And it’s one that readers would all do well to keep at the forefront of our minds as well.

The book’s eight chapters contain a rich variety of historical narratives, political insights, personal narratives, and cultural inflection points. She lays out the urgency of solidarity at this historical moment before diving into a kind of coming out narrative as an anti-Zionist Jew, set against her experience of being charged as an antisemite at CUNY (City University of New York).

Throughout the volume, she weaves together two critical elements: her experiences with various political movements and highlighting cultural and political figures whose activism and cultural production illuminate the complex ways in which people try to confront structures of power, however imperfect those attempts might be. All of these pieces come together in surprising and powerful ways that encourage readers to envision how to persevere in this political moment.

The way Schulman narrates her long history of organizing is fascinating and enriching. Whether it’s her participation in the transnational underground abortion movement in 1979 or her involvement in ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), these experiences provide examples of how one can act with creative, bold actions in highly-charged political moments. One of the most significant lessons she learned from her involvement with ACT UP was to root her work among “three guideposts: intervention, listening, and being effective. Over the years, I have come to recognize at least these three basic responsibilities to be at the root of active solidarity” (46). Schulman juxtaposes this insight amidst the encampments on American college campuses, encouraging her readers to grow the communities they’ve established, especially given the forces they are up against:

“The powers we oppose are large, and refusing to be complacent, educating and transforming ourselves, and making winnable demands in strategic ways is a long path, but our best path. Egotistical expectations of quick victories and immediate impact are not our friends when we face such powerful forces as the United States and its paralyzing hold on the United Nations. Renewed creative approaches, fun in growth and togetherness, and supporting each other in refining our strategies are our strengths.” (45)

Against this backdrop, Schulman’s imperative that we not only listen, but also hear Palestinian voices is critical because it’s so challenging to do so given the media’s conglomerated power.

In important ways The Fantasy and Necessity of Solidarity builds on Schulman’s previous fiction and nonfiction writing, which traverse manifestations of the feminist imperative that the personal is political. It’s a sensibility that enables her to draw a through-line from her Zionist family history to parallels between American actions towards Jewish refugees during World War II and the current genocide in Gaza. That reflection engenders taking responsibility for herself and others. Teasing out one’s relationship to the ongoing genocide forces you to think about your complicity in the conglomerated power structure.

Conglomerated power flattens the kind of thoughtfulness evident in Schulman’s prose, especially when she’s excavating her work in the BDS movement. She models how one can listen, reevaluate, and grow in solidarity. Sharing how she previously understood her role as providing support for the movement, Schulman shares the moment when she learned otherwise: “After each task was complete, I kept asking the people I was working with, ‘What do you want me to do next?’ Finally, one leader, Haneen Maikey—at that time the director of alQaws, a Palestinian queer organization—just said to me, ‘It is not my responsibility to think up your strategy’” (48). This revelation instructs readers how to engage in solidarity with others by pushing us to strategize without making those we’re supporting do all the labor for us.

Schulman narrates the fruits of organizing a successful BDS campaign—at the epicenter of American culture’s conglomerated power in Hollywood no less. She participated in a behind-the-scenes campaign, with thirty-five other people, to intervene in an award-winning television program’s plans to shoot part of its season in Israel. Joey Soloway, creator of Transparent, was planning to travel with their cast to Israel to film season four. The effect of boycott activists reaching out to Soloway changed the program’s focus to not only halt the on-location scenes, but it also changed the course of the storyline to include queer Palestinian characters. The essence is the vital role of listening, “If more people with actual power were willing to listen and talk and go through an experience of exchange of ideas, change would come a lot faster and go further. And as my own experience of this movement always shows me, people needing solidarity are often available to talk” (166).

Of course, the scenarios in which people are open to speaking are not as common as we would like. Schulman’s reflection on other attempts at building solidarity helped her to gain clarity about some barriers to conversation and support among our peers: “It becomes clearer and clearer to me that the force keeping us apart from each other is, in a sense, rooted in an idea of supremacy built upon the fiction of standards. Qualification seems to be a kind of propaganda, firmly in place to justify the unfair exclusions that require solidarity to dissolve” (69).

Supremacist thinking is what Schulman was confronted with when she was collecting signatures for a petition to support poet Dareen Tatour after she was arrested for posting her poem “Resist, My People, Resist Them” on Facebook. Schulman’s example of one prominent writer who wanted to evaluate the poem for themselves before signing the petition revealed how the fiction of standards is an impediment to solidarity. For Schulman, it’s unconscionable that one would want to appraise a poem before deciding whether it’s worthy of its author being incarcerated.

Schulman has other tales to tell from organizing in the culture industry and on university campuses, some of which do not end with positive results. But the methods used and the reasons for failure are important for activists to ponder. At the heart of most of these attempts to create change is centering relationships and communication. On a larger scale, Schulman argues that relationships within conglomerated power are what we wrestle with on institutional and personal levels: “In the end, many people are driven by a fear of losing opportunities. Many think of themselves as having good politics, but living what we believe is a different challenge. Solidarity helps us think of ourselves in close proximity to afflicted people whom the machine keeps outside consciousness” (171).

Schulman’s vision of solidarity exists in a world where we are accountable to one another and can cross identify with each other. It’s a lesson she has clearly harnessed from years of activism as well as her work as a writer who is observant of lives in her midst and on the page. It is possibly why she peppers each chapter in this book with narratives of artists and activists whose stories reveal the complexity of living a life of struggle: organizer Wilmette Brown, artist Alice Neel, Author Jean Genet, novelist Carson McCullers, and artist Bryn Kelly. In fact, the final chapter of the book is a transcript of a talk Schulman gave with Morgan M. Page in Montreal as a post-mortem of Kelly’s suicide.

The penultimate chapter may appear to some as a break from the rest of the volume. But it isn’t. Schulman ends on a note of modeling what it looks like to be in solidarity, be self-critical, and engage with people’s questions about your actions as a way of holding yourself accountable. Schulman’s insights in this chapter demonstrate what it looks like to reflect on one’s mistakes. Although its form is a transcribed public lecture, the chapter is deeply personal. It leaves readers with an understanding of how different strategies of organizing may not work across the generations.

Ultimately, Schulman concludes The Fantasy and Necessity of Solidarity on a hopeful note in spite of the genocide we’re living through. In spite of the cancel culture that plagues anti-Zionist writing, lectures, events, or the frustration that our actions are not met with instant change, she leaves us with this nugget:

“No power structure is stagnant. Healing takes place in relationship, and that is personal and also social. New approaches, understanding, and conversations are needed now and will always be needed. Solidarity is our way of life, and to keep it breathing, innovation is our friend. My motto for these coming years is: ‘Don’t stop yourself from doing what you think is right. Make them stop you.’ And I hope to keep that in solidarity with many of you.” (215)

Conglomerated power may still fail us in the realm of culture, universities, government, and the media. But our solidarity is building, and our creative actions are expanding. Schulman reminds us that the success of such momentum is worth ruminating over as we continue to struggle for Palestine’s liberation, which will be liberating for us all.