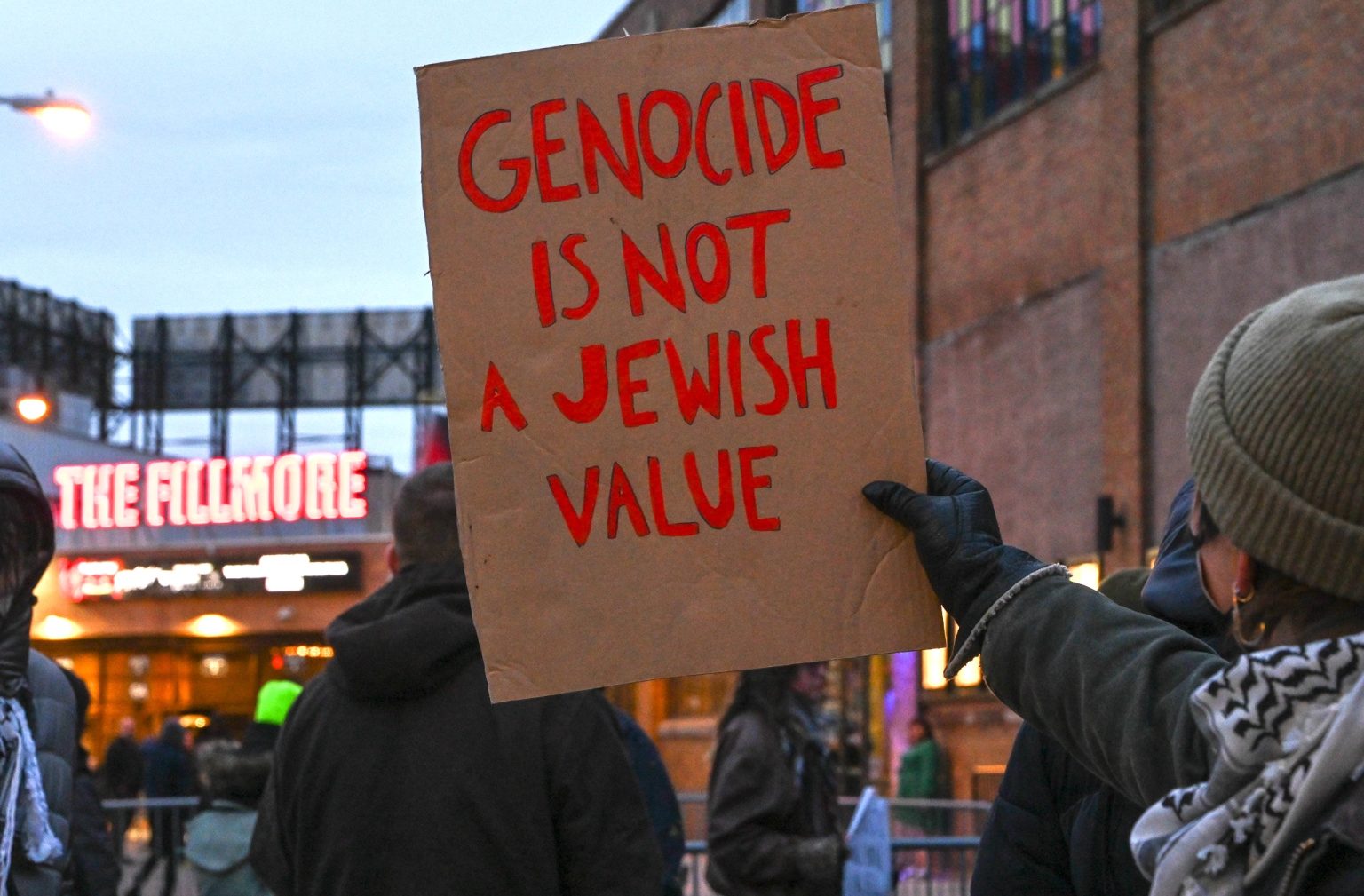

Activists at a demonstration against the pro-Israel singer Matisyahu in Philadelphia, on March 22, 2024. (Photo: Joe Piette/Flickr)

What role does Jewish anti-Zionism actually play in Palestinian history? Does it change political outcomes? Has it ever altered the systems that organize Palestinian dispossession? Or does it primarily operate inside Western — often Jewish — moral and political worlds, gaining prominence at precisely the moments when Palestinians require something else entirely: pressure, leverage, interruption, consequence?

Gaza is being destroyed in real time. Tens of thousands of Palestinians have been killed. Entire neighborhoods have vanished. Hospitals, schools, universities, refugee camps reduced to rubble. Families erased. Lives shattered.

A genocide is underway. A century-long struggle continues. Yet public conversation often drifts back to Jewish self-examination, while Palestinian history, political demands, and political strategy are pushed to the margins.

This discourse is not new. What is new is the scale of devastation and the urgency of the Palestinian experience that is being displaced.

The drift toward Jewish moral reckoning

Over the past year, Jewish anti-Zionist voices have become far more visible in the media discourse. This is happening for several reasons.

First, the scale and visibility of Gaza’s destruction have shattered decades of political cover and stripped away the moral framework that once sustained liberal Zionism. For many Jews raised within that framework, the rupture is profound and has led many, especially young Jews, to reject the mainstream Jewish organizations that have been in near-total alignment behind Israeli violence. This has not only become a critique of Israel but a revolt against communal authority.

Jewish activists have confronted communal leadership, walked out of institutions, organized mass protests, and publicly rejected Zionism. This shift matters. Jewish dissent has weakened longstanding taboos and opened space for Palestinian voices that were previously suppressed.

However, alongside this disruption, another pattern has emerged.

As Gaza burns, Western media increasingly frames the moment solely as a crisis inside Jewish communities. Coverage in major outlets centers Jewish disillusionment, generational conflict, and identity rupture as the key to understanding what is happening.

In these stories, Palestinians appear mainly as the trigger for Jewish transformation. But it is essential to acknowledge that Palestinian journalists, medics, organizers, and families — surviving under bombardment, documenting atrocities despite blackouts, organizing massive protests across the world — forced Palestine into global consciousness at a scale not seen in decades. Jewish anti-Zionist speech expands inside this space. It does not create it.

The danger is that Palestinian catastrophe simply becomes the backdrop for a moment of Jewish moral transformation.

A BBC segment in October 2025 on Jewish protesters in New York made this painfully clear. The camera followed Jewish activists through their emotional journeys — betrayal, awakening, rupture. Only near the end did the program cut to Gaza, where a Palestinian mother said, “We hope the world will listen now that others are speaking for us.” Her words were framed not as a political demand but as gratitude that Jewish voices had finally entered the conversation.

The effect is quiet but powerful. Palestinian catastrophe becomes meaningful mainly when it triggers Jewish moral change.

When the Gaza genocide is narrated as the moment “many Jews finally woke up,” decades of Palestinian dispossession are compressed into the background of a Jewish ethical story. Palestinian history becomes the stage on which another community’s moral drama is performed.

This does not erase Palestinians. It recenters the story away from them.

A familiar Western pattern

For Palestinians, this displacement carries real political cost. Their struggle is no longer understood as an ongoing confrontation with a system of military rule, land theft, siege, and apartheid. Instead, it becomes a moral mirror for others.

This pattern is not simply a feature of the present moment. It reflects a long-standing habit in Western political culture.

For decades, Palestinian political life has been rendered legible mainly when it passes through Western institutional filters that privilege the moral narratives of others — diplomats, journalists, scholars, humanitarian officials, and, critically, Jewish interlocutors — over Palestinian political agency itself.

During the Oslo years, Palestinian resistance was recast as a problem of “confidence-building” and “mutual recognition” with Jewish Israelis while the material architecture of occupation expanded relentlessly on the ground. After 9/11, the Palestinian struggle was reframed through the language of counterterrorism and security management, reducing a national liberation movement to a policing problem. In each period, the same mechanism operated: Palestinian history was acknowledged only when it could be absorbed into another framework of legitimacy.

The present moment follows this familiar logic. Palestinian destruction is again rendered meaningful mainly as the catalyst for transformation elsewhere — now as the trigger for Jewish ethical crisis. This shift does not deny Palestinian suffering. It reorganizes its political significance.

Concrete examples are increasingly visible. Major Western outlets devote sustained coverage to internal struggles the the Jewish community — synagogues in crisis, federations under pressure, generational rifts — while Palestinian political analysis appears in fragments, often reduced to scenes of devastation or appeals for sympathy. Even inside solidarity spaces, media attention gravitates toward Jewish activists as interpretive guides, their statements treated as especially authoritative or reassuring for Western audiences.

This dynamic also operates inside movement structures. At several large demonstrations in 2024 and 2025, Palestinian organizers I was in conversation with reported pressure — from journalists and allied organizations alike — to foreground Jewish speakers in order to “broaden appeal” or “reduce backlash.” In some cases, Palestinian groups were urged to allow Jewish organizations to re-frame events whose political objectives had been developed by Palestinians themselves. The result was not erasure but displacement. Palestinian strategy and demands receded behind a narrative of Jewish moral awakening.

This is the deeper risk of recentering. The story of Gaza becomes less about confronting the systems that produce Palestinian death and more about managing Western moral injury. Palestinian time — marked by land confiscation, siege, incarceration, and generational displacement — is subordinated to the tempo of Western ethical reckoning.

That reorientation carries material consequences. When Gaza is framed mainly as a moral shock to Western conscience, the political response gravitates toward statements, condemnations, and symbolic gestures. When it is framed as a crime sustained by concrete systems — such as arms transfers, financial flows, diplomatic protection, and legal impunity — the response begins to target the machinery that enables the crime.

The struggle over narrative orientation is not semantic. It determines whether the present moment produces meaningful pressure on the structures of domination or dissipates into another cycle of moral reflection.

What this moment demands

From a Palestinian perspective, the political usefulness of Jewish anti-Zionism is measured by one standard: does an intervention weaken the systems that sustain dispossession?

Moral clarity alone does not dismantle military power, arms transfers, financial support, diplomatic protection, or legal impunity.

Jewish anti-Zionism becomes politically meaningful only under specific conditions, which include confronting real centers of power, including governments, arms manufacturers, banks, courts, media institutions, and universities. This also means rejecting the tendency to treat Jewish voices as authorizing Palestinian claims, and foregrounding Palestinian demands in a way that recognizes and counters the the asymmetry in power that exists between Jews and Palestinians in the broader discourse.

It is also essential that Jewish anti-Zionists know when to step back. At key moments — such as South Africa’s genocide case at the International Court of Justice — Jewish groups amplified Palestinian legal submissions without recentering themselves. Sometimes the most effective intervention is not interpretation, but amplification.

Under these conditions, Jewish anti-Zionism can fracture elite consensus and weaken the ideological shield protecting Israeli violence. Without this orientation, it risks drawing the story back into Jewish self-reflection.

This is important because Jewish anti-Zionists now occupy positions of visibility inside institutions that long excluded Palestinians. That visibility can destabilize entrenched narratives. It can also reproduce familiar habits of moral self-focus.

Interventions that foreground Palestinian political demands apply pressure to the systems sustaining dispossession, but interventions that center Jewish moral reckoning pull the moment back into established narrative comfort.

Political change rarely follows the maturation of conscience. It follows shifts in power: when legitimacy fractures, alliances reorganize, and the costs of maintaining a system rise.

Solidarity that drifts into ethical self-reflection while Gaza burns loses its political force. Solidarity that targets arms manufacturers, funding pipelines, diplomatic shields, and legal impunity becomes part of the pressure capable of altering the calculus of dispossession.

This moment calls for interventions that shift structures rather than attention, reinforce Palestinian analysis rather than absorb it, and operate where leverage exists rather than where comfort lies.

Jewish anti-Zionism becomes consequential when it moves along this axis. It loses consequence when it circles back toward itself.