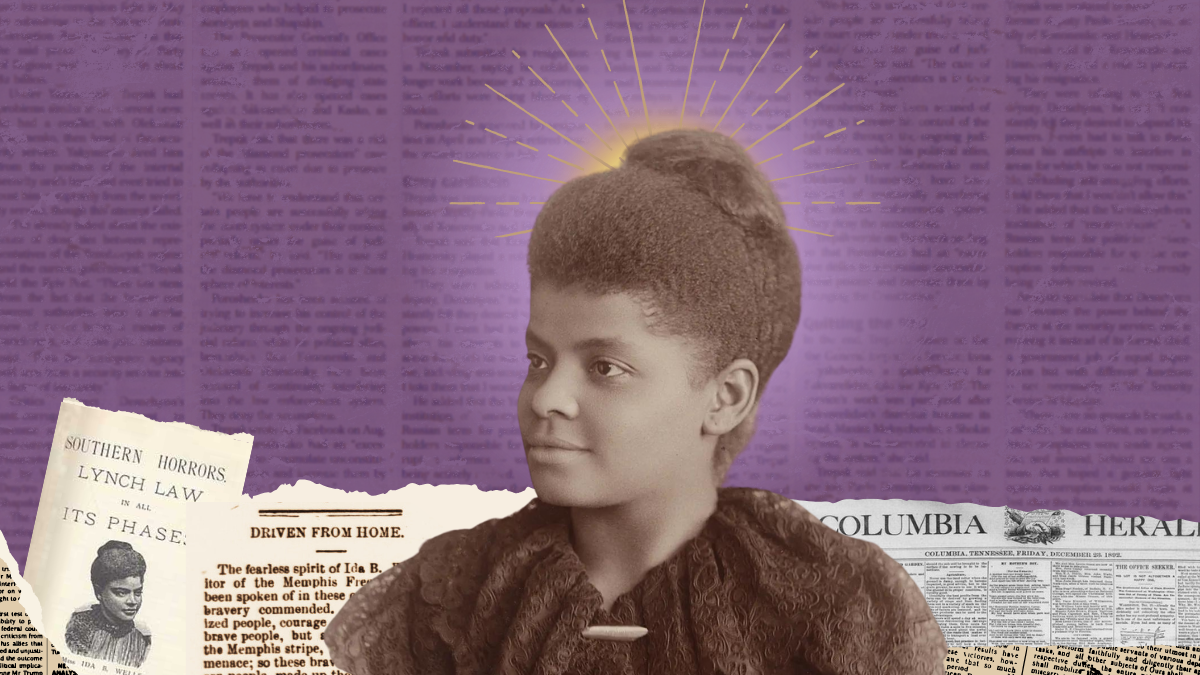

Designed by Lara Witt

Springtime in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1892 should have been a time of rebirth and reconnection. The city was making history and welcoming more commerce with the grand opening of the Frisco Bridge. At the time, it was the longest bridge in the country and the first bridge connecting Memphis to Arkansas for railway traffic. Locals gathered for a dayslong celebration to mark the occasion despite heightening tensions in the area.

While Memphians gathered on the riverfront for parades and fireworks, Ida B. Wells was pouring over her research on what is now known as the People’s Grocery lynchings, which had happened two months earlier. Thomas Moss, a Black grocery store owner, and his employees, Calvin McDowell and Will Stewart, had been lynched by a white mob. On May 21, 1892, Wells published her findings in Memphis Free Speech, the newspaper of which she was co-owner and editor. It lit a rhetorical match.

Wells’ editorial recounted the number of Black people lynched across Arkansas, Alabama, Louisiana, and Georgia, including Moss, McDowell, and Stewart. She exposed the “threadbare lie” at the center of the violence—that Black men regularly and wantonly assaulted white women. Less than a week later, a mob of white supremacists ransacked the newspaper’s office while she was away traveling and warned her not to come back to Memphis.

Wells’ words—and the violent backlash they received—remind us of the importance of Black journalists willing to tell the truth, even under the threat of racial hierarchy and power. The lie she was refuting was so pervasive that it was also at the center of one of the most infamous white supremacist terrorist attacks in U.S. history—the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre.

Almost 30 years after the mob of white supremacists destroyed Wells’ newspaper presses, another newspaper brewed up anti-Black violence 400 miles west of Memphis. On May 31, 1921, the white-owned Tulsa Tribune sounded a clarion call to white terrorists with an incendiary headline—“Nab Negro for Attacking Girl In an Elevator.” The editorial came after 19-year-old Dick Rowland reportedly stumbled while entering an elevator and stepped on the white 17-year-old elevator operator’s foot. This account is backed up by numerous Black newspapers and reported by Walter White, the future director of the NAACP, for a June 1921 edition of The Nation. Unsurprisingly, the Tulsa Tribune reported the incident differently.

The Tribune article sparked 18 hours of white supremacist terror. White’s The Nation piece reported that the white supremacist mob killed between 150 and 200 Black Tulsans during the massacre, which led to $1.8 million in property damage concentrated primarily on Tulsa’s Greenwood neighborhood, which included what’s colloquially known as “Black Wall Street.”

Without the investigative reporting techniques that Wells innovated in the late 19th century, like aggregating data on lynchings from newspapers and public records and using eyewitness testimonies from families of the deceased, we might only have the sensationalist, violently inaccurate accounts of the Tulsa Race Massacre—like the article published in the Tulsa Tribune.

Wells and White belong to a lineage of Black journalists whose most impactful work was proving that stories like this were almost always a cover for white supremacist violence.

There is a throughline from the legacy of these Black journalists to today. Although mainstream news only selectively covers stories of government wrongdoing and negligence, BIPOC newsrooms fill the gap by accurately reporting on how society functions.

For instance, in February 2023, The Jackson Advocate reported on how political leadership at the state level exacerbated the Jackson, Mississippi, water crisis. The Advocate collaborated with the Pulitzer Center and The Nation to provide accurate coverage, compared to other local newsrooms, which only focused on the absence of water and not the root cause.

Months later, the Kansas City Defender broke a national news story. In April 2023, the Defender broke the story of Ralph Yarl, a Black teen shot by a white homeowner after Yarl mistakenly rang the wrong doorbell to pick up his younger siblings. Notably, the Defender began the headline with five definitive words that likely would never be published by a status quo, mainstream outlet: “This is a hate crime.”

In Memphis, the birthplace of Wells’ Free Speech, the nonprofit newsroom MLK50 uncovered new details of the city’s lead crisis just last year. This reporting exposed the many areas of life that this public failure had branched into, such as education, healthcare, and public safety. MLK50’s editor and publisher Wendi C. Thomas continues Wells’ legacy as a Black woman investigative journalist living and working in Memphis.

The Advocate, the Defender, and MLK50 are testaments to the community transformation possible when we invest in BIPOC newsrooms. But what does thorough investment look like?

The Racial Equity in Journalism (REJ) Fund at Borealis Philanthropy is working to answer that question. The REJ Fund fosters a culture of repair by organizing and distributing capital and resources for journalists and publishers of color. The fund recently commissioned research that analyzes four financial models of sustaining BIPOC journalism and paints a picture of what we stand to gain by implementing each one. Cumulating in a report entitled “Repair, Reimagine, and Rebuild: Modeling the Future of News For and By Black, Brown, and Indigenous Communities,” this work is a call to elevate the necessary components of a media landscape that genuinely serve democracy: community engagement and education.

The most comprehensive scenario in the report, Abundance, Repair, & Reimagine, calls for seeding and building out local news ecosystems across the country for critical racial and ethnic communities and would require an investment of $71 billion annually. The report has several other scenarios, including community-led journalism, statewide collectives, and ecosystem-building hubs. This final scenario, costing $360 million, focuses on strengthening media ecosystems in the 26 most multi-ethnic cities in the U.S. While its price tag is the least lofty of the four, this model is also the most geographically fragmented and disconnected—much like the current state of resourcing BIPOC journalism.

The industry must ensure that our media is genuinely a cornerstone of democracy by focusing on the investments described in the Abundance, Repair, & Reimagine scenario. This scenario represents an integrated and well-resourced tapestry of outlets with journalist positions especially equipped to study and translate government policies and actions to audiences. This model means that news audiences can spend less time and energy trying to decipher the corporate speak of mainstream news and more time learning our societal truths so that we can collectively organize and act for a more just world.

We need this investment in community journalism more than ever now. Even by their own standards of objectivity and neutrality, mainstream outlets have failed all audiences, not just communities of color. We see it now in the vast gulf between coverage of Israel’s military strikes and the siege on Gaza. The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, and The Washington Post have all been criticized for consistently biased coverage against Palestinians, according to The Intercept.

In contrast, BIPOC-led and -serving journalism educates, increases proximity, and inoculates against misinformation, which is evident in the coverage of publications like The Objective and youth-led media organization Shift Press.

Wells didn’t set out to be a journalist. She was a school teacher who was fired after publicly criticizing—in print—the deplorable conditions that Black children were made to endure in Memphis schools. This is how many BIPOC journalists are made: by uncovering and spreading hard truths. More than a century later, we still collectively reap the benefit of her work, and we desperately need more truth-tellers like her. We get there by investing in repairing, reimagining, and rebuilding our journalism ecosystem.