Photo by Johnny McClung/Unsplash/Creative Commons

(RNS) — When in September 2021, Pennsylvania’s Central York School District banned “The Arabic Quilt,” Aya Khalil’s award-winning debut picture book about fitting in at school, Khalil decided to write a book about her experience. “The Banned Books Bake Sale,” due out in spring of 2023, is about a young woman who fights a ban at her school by telling about experiences in the Egyptian “Arab Spring” revolution of 2011.

The experience also prompted Khalil to redouble her support of Kidlit in Color, a group of children’s book authors who are trying to create more diversity in children’s literature.

With the rise in book bans across the country, purportedly aimed at suppressing the teaching of critical race theory and other anti-racist ideas, books for and about Muslims, already rare in school libraries and curriculums, are increasingly being put out of reach for young readers.

When Khalil helped to launch Kidlit in Color in 2019, the group’s primary focus was to shift attitudes toward diversity in the publishing industry. “I started Kidlit in Color because I wanted to be part of a group of BIPOC authors who shared the struggle of the publishing world but also the struggles of being from a marginalized community in the publishing world,” Khalil explains.

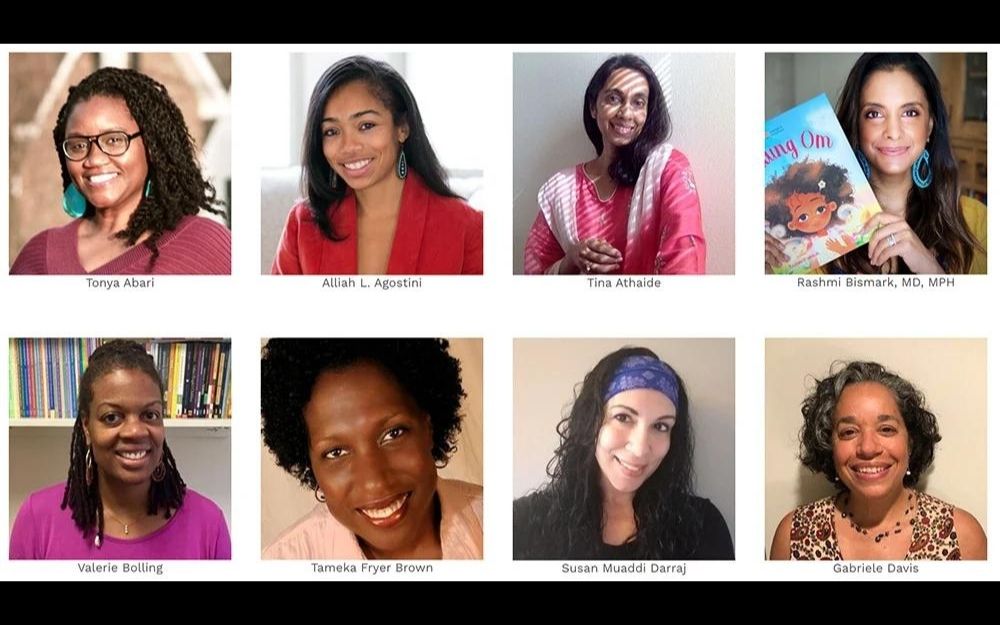

Some of the authors highlighted on Kidlit in Color. Screengrab

As the U.S. Muslim population grows, parents looking for books that recognize the existence of Muslim children have few choices. Books in English that teach Muslim values or tenets of the faith are even rarer. “It would be nice to see editors and agents specifically look for these types of books,” Khalil said.

But the racially oriented book bans have made the group’s advocacy even more important, she said. “It’s really dangerous, especially because books by Black Muslim authors were on that ban list a few months ago, and there are very few Black Muslim authors,” explained Khalil, who is an immigrant from Egypt.

For authors like Khalil, the bans have highlighted the need for schools to de-escalate diversity as a hot-button issue. Their goal is not to inculcate children with Islamic ideas, only to recognize the existence of Islam on the American religious landscape and to welcome Muslims of color as neighbors.

Author Aya Khalil. Courtesy photo

Khalil’s books, for instance, aren’t designed to teach Islamic topics. Rather, her characters show they are Muslim in subtle ways. “A mom wears hijab outside of the home and not in the home, showing kindness toward others, standing up for what’s right and caring for the elderly,” she said. “That’s all important for Muslim kids to see and gets the conversation going for Muslim kids and their parents.”

Even the idea of protesting a book ban, she said, is in line with Islamic values. “In Islam,” she said, “we’re told to speak up when we see something wrong.”

Reem Faruqi, author of several children’s books including her most recent Golden Girl, notes the importance of books that highlight a diversity of Muslim experiences. “When I write about a Muslim character, my story does not represent every Muslim out there. I think editors should keep reading and publishing Muslim stories and know that we do have a variety of stories to tell,” she says.

In 2019, the Cooperative Children’s Book Center at the University of Wisconsin received nearly 4,000 children’s and young adult books from publishers; of those books, only 1.2% were “tagged” with a Muslim diversity subject.

Cristina Soto, a youth services associate at the Green Hills Public Library in Palos Hills, Illinois, near Chicago, said Muslim representation in children’s fiction is beginning to emerge but still has a long way to go. “There is still a big gap in Muslim children’s books compared to other minority or ethnic groups,” Soto said.

Soto said negative stereotypes about Muslims begin to fade when positive media portrayals and literature about the Muslim community emerge. Children’s literature, she said, is the perfect place to start.

“People learn a lot about diverse cultures by sharing stories about different celebrations and customs,” Soto explained.

Photo by Susan Q Yin/Unsplash/Creative Commons

A 2006 study by Lori Cohen and Leyna Peery found that students who read texts about Muslim women began to dispel preconceived assumptions. Consequently, students ultimately had “more fair and realistic” perceptions of Islam.

Chicago Public Library children’s librarian Liv Hanson said the other effect of including Muslims in children’s books is to make Muslims themselves feel more welcome. “Greater and more diverse representation of Muslim youth and experiences will allow some readers to see themselves and their families in stories and will help all readers build appreciation and understanding for one another,” said Hanson.

So far most titles that answer this call have come from publishers focused on the Muslim market. In 2012, Shade 7 Publishing, a British company started by Hajera Memon, brought out Medeia Cohan’s “Hats of Faith,” which pictures people wearing a turban, hijab and a kippah, as well as African head wraps and headgear commonly worn by rastafarians, Sikhs and other cultures and faiths.

Author Hajera Memon. Photo courtesy of Shade 7 Publishing

Most Muslim publishers are still primarily attuned to parents’ wishes to pass on their faith to their children. Memon’s 2013 pop-up book, “The Story of the Elephant,” tells of the ancient tyrant Abraha’s attempt to destroy Mecca with an army mounted on elephants in the century before Muhammad founded Islam, with a map and press-out elephant figures to help children recreate the scenes. The story of Abraha is mentioned in the Quran, and Memon’s book incorporates lessons about trusting God to save the faithful.

As a Muslim mom living in Southern California, Asma Wahab knew she wanted her child to have a different experience with learning the Quran than she did. “Growing up I found learning Arabic to be very difficult and boring,” said Wahab.

That meant finding resources to teach simple Arabic, the language of Islam’s holy text. In 2018, Wahab founded Civilian Publishing. “I wanted to make books that were engaging, fun and beautiful so that kids could be excited about learning the Arabic language from a young age,” Wahab said.

These books may not make it onto the mainstream children’s shelf at the bookstore or library shelves, but wherever children encounter them — in their homes or their friends’ homes — they have a profound impact on how they see the world and where they fit in it.

This article was produced as part of the RNS/IFYC Religious Journalism Fellowship Program.

By Tasmiha Khan