Imam Omer Bajwa, left, in Feb. 2020. Photo courtesy of Yale Chaplain’s Office.

(RNS) — Years before he became Yale’s first full-time Muslim chaplain, Imam Omer Bajwa was a graduate student and aspiring journalist who had little idea of what a chaplain does.

Then came September 2001.

“Our phones started ringing off the hook,” said Bajwa, who was involved with Cornell’s Muslim Student Association at the time. “We’re in Ithaca. There’s no mosque, no local Muslim leadership. All these high schools and public libraries and radio stations and college campuses are calling for panels on Islam and understanding 9/11… that was a pivotal moment.”

Energized by the teaching opportunities and interfaith engagement, he abandoned journalism to enroll in an Islamic studies doctoral program. But the academy soon began to feel too isolating. A few twists and turns later, he stumbled upon a perfect fit: Islamic chaplaincy.

Today, Bajwa is the director of Muslim life at Yale University, where he has been since 2008. With Muhammad A. Ali, Sondos Kholaki and Jaye Starr, Bajwa is also editor of the new book “Mantle of Mercy: Islamic Chaplaincy in North America,” a collection of 30 first-person accounts by a wide range of Muslim chaplains. The book captures a critical moment in a specialty that is steadily gaining momentum: Since 2010, at least four new graduate programs in Islamic chaplaincy have popped up across the U.S., and during the pandemic the decade-old Association of Muslim Chaplains doubled its membership to 234.

“Mantle of Mercy: Islamic Chaplaincy in North America” Courtesy image

“Mantle of Mercy” addresses topics as varied as tensions between Sunni and Shia prison inmates, and micro-aggressions in military settings. “Our dream and prayers were for it to be a field-defining book, to set up the field and open up a space for reading the history of Muslim chaplains in North America,” Bajwa told Religion News Service.

Chaplains differ from imams in that they emphasize pastoral care, not congregational leadership, and are usually employed in a secular setting and therefore are expected to serve people of any spiritual background. Chaplaincy, unlike some Islamic leadership positions, isn’t restricted to men.

Though they’ve been around for decades, many Muslims are still unfamiliar with the function of chaplains. “Chaplaincy is not an Islamic term,” Bajwa explained. “There’s no Arabic word for chaplain.”

But Bajwa’s co-editor, Starr, said that while Muslims only adopted the term in the late 20th century, Islam has a long history of pastoral care. She pointed to the Hadith, a collection of the Prophet Muhammad’s sayings and actions.

“There are beautiful stories about the way that he paid attention to every person that came to him,” said Starr. “He turned his body. He faced them fully and he listened. And it doesn’t matter who they were, if they were somebody who was wealthy and powerful or if they were somebody who was poor.”

Chaplaincy first entered the North American Muslim scene in the 1970s, when Black Muslims took on ministerial work in U.S. prisons. In the 1990s, Muslim chaplains arrived at universities, usually as part-timers or volunteers and in hospitals, according to Starr. It wasn’t until the 2000s, though, that the field truly began to pick up steam.

“For a long time, all of the material available was through the Christian lens,” said Starr. “Sometimes you’d get a Jewish piece, and you’d have to translate or sort of put on your Islam glasses and figure out, what does this mean for me in my context?”

Today, most Muslim chaplains hold a divinity school degree in Islamic chaplaincy or an equivalent. But though the field is professionalizing via associations, graduate programs and now its own literature, the landscape of Muslim chaplaincy is as diverse as the individuals who belong to it.

“As you can see from the essays, we share many of the same principles, but it’s beautiful to see how that manifests in our own ministries and caregiving,” Kholaki told RNS. “Each one of us will approach chaplaincy slightly differently because of what informs us from the prophetic tradition or from Scripture.”

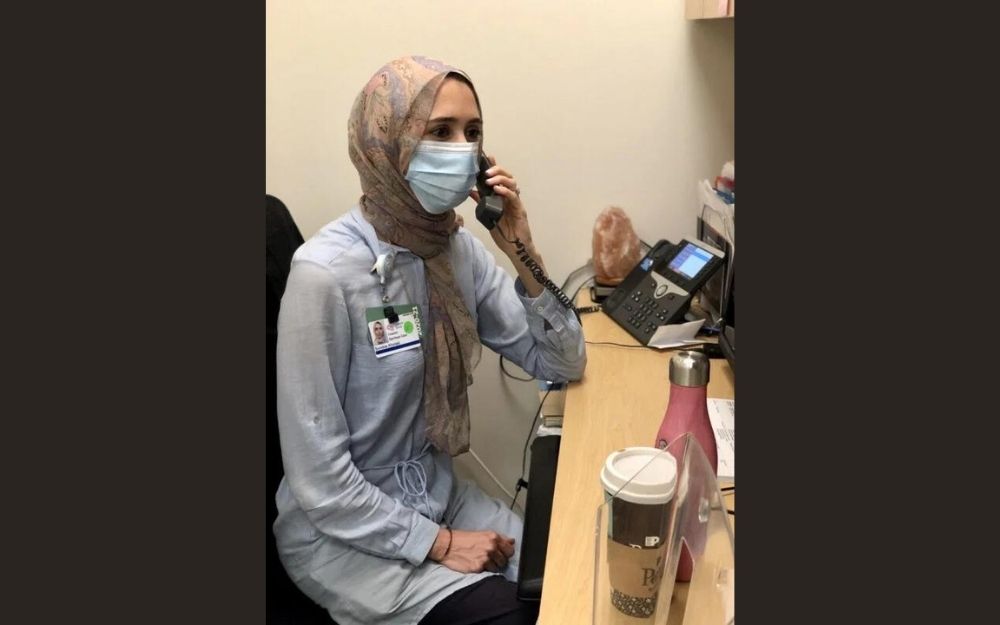

Sondos Kholaki during work. Courtesy photo

Kholaki, a staff hospital chaplain in Southern California, describes in the book how the five pillars of Islam — including fasting, a discipline many Muslims are practicing now, during Ramadan — inspire her approach to care.

“Fasting is not just a physical emptying, where we are literally not eating anything; there is a very metaphysical aspect to it,” Kholaki said. During Ramadan, she believes, God sends her some of her most challenging cases because she’s most ready for them.

“I come in completely emptied, and able to really sit and listen,” she said. “I can offer so much more when I am 100% in the moment, when I am slowed down or pulled back to my lowest speed of functioning. I’m not in a hurry to get anywhere or do anything. And the personal connection and consciousness I feel with the divine, having that at the forefront, will impact what I say and the thoughts I have.”

Starr, who is training to become a hospital chaplain, said the Prophet Muhammad’s compassionate presence is something she seeks to emulate, even when a patient refuses to see her because she is Muslim.

“I don’t hold hostility toward them for that. I continue to check in with the team to make sure they’re okay, and see if somebody else can check in,” said Starr. Oftentimes, however, if she continues to respond to the patient with warmth, she said, they begin to open up.

At Friday services at Yale, Bajwa tries to reflect the inclusiveness that the prophet projected at his own mosque. “In our space, women have full accessibility, graduate students come with families, there are kids in strollers,” said Bajwa. “Why? Because the prophet’s mosque was what we’d now call welcoming and inclusive. It was multi-generational and multiracial.”

The welcoming space reverses the frustrating racial and ethnic divisions Muslim students often find in local Muslim communities. Chaplaincy, Bajwa said, can also support students navigating both heightened Islamophobia and a suspicion of authentic religion more generally.

“They want to live in a pluralistic cosmopolitan society where they accept others but also want others to accept them and their religious identity, ethical choices and moral commitments,” he said.

Captain Barbara Lois Helms, center, a unit chaplain with the Canadian Armed Forces, in 2006. Photo by Bdr Maxime Cote

As Gen Z Muslims wrestle with questions of spiritual identity, the editors of “Mantle of Mercy” hope their book might persuade some students to join their ranks. The need for Muslim chaplains will only grow — a Pew study from 2018 projected that by 2050, the U.S. Muslim population would nearly double to reach 8.1 million, or 2.1% of the total population.

“My biggest hope would be that everybody will walk away more comfortable with Muslim chaplains,” said Starr. “And if that is a Christian supervisor who would have never thought of hiring Muslim chaplains … I hope that they will realize that a Muslim chaplain is an asset to the team and can care for all of the patients just as well as a Christian chaplain.”

By Kathryn Post