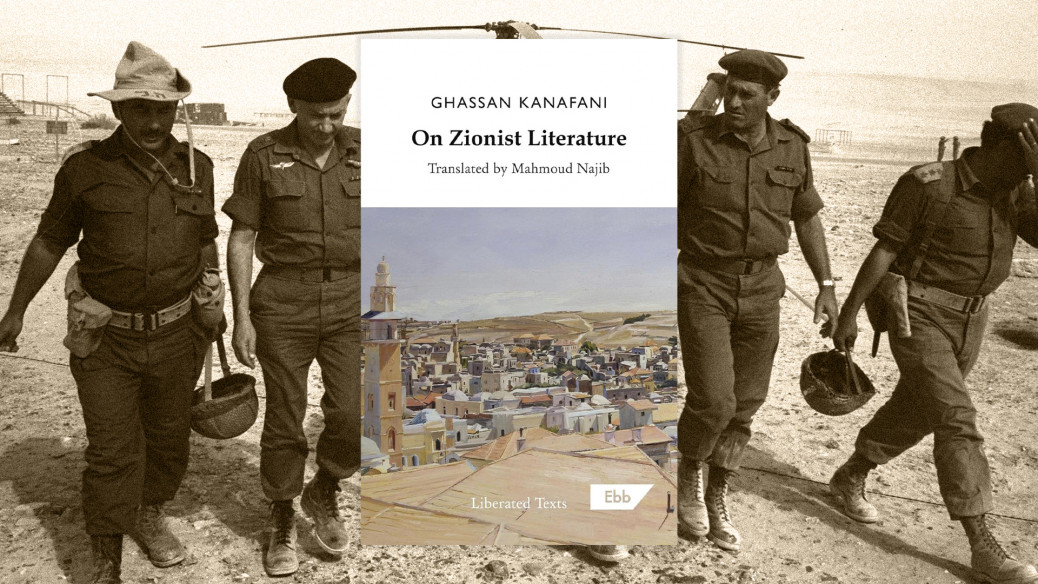

Ghassan Kanafani’s On Zionist Literature makes an incisive analysis of the literary fiction written in support of the Zionist colonisation of Palestine [Ebb Books]

Written in 1967 in Arabic and recently translated into English, Ghassan Kanafani’s literary critique on Zionist literature in 19th-century Europe and its influence is a must-read in an era where Palestinians are living and experiencing colonialism in a supposedly post-colonial era.

In the introduction to On Zionist Literature, (Ebb Books, 2023) Steven Salaita notes: “Ghassan Kanafani’s fierce counterpoint to Zionist literature aims to show that Palestinian revolutionary sentiment and national liberation are indispensable to the creation of a better world.”

To dominate Palestine, Salaita writes, Zionism needed both mobilisations for the colonial project, which it found among Victorian writers, as well as rewriting and revision of history. George Eliot, for example, called for the establishment of the Jewish state 70 years before the 1948 Nakba.

The publishing industry, Salaita states, is included as a site of imperialist politics, along with cultural institutions. Anna Kanafani, Ghassan Kanafani’s wife writes in the preface to the translated edition of her getting to know him and the impact of his writing. While noting that “Zionist influence on European media was almost total,” she also reflects that “Ghassan was the commando who never fired a gun.”

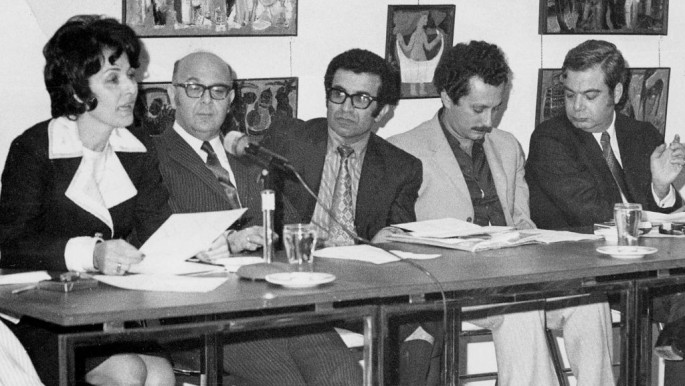

Pictured here in Beirut in 1975, Ghassan Kanafani [second right] is considered to be one of the Arab world’s finest writers [Getty Images]

Kanafani starts his critique thus: “It would not be an exaggeration to assert that literary Zionism preceded its political counterpart.”

It is literary Zionism that gave rise to political Zionism – an important observation that Kanafani emphasises to impart a succinct sentence describing his endeavours: “All that this study hopes to achieve is to shed new light on that exacting principle – know your enemy.”

To achieve this, Kanafani embarks on a study of literature and the use of language, giving a historical overview of Zionist history that is not only mostly overlooked, but rarely dissected in detail.

Demythologising Zionism

Hebrew, Kanafani writes, was given importance by Zionism as the ideology made the language a unifying factor. The political plans Zionism had for the Hebrew language led to eliminating the importance of Yiddish – Zionists were against Jewish people speaking Yiddish, for example.

Hebrew became associated with the Zionist political ideology rather than with its religious roots, hence the political instrumentalisation of religion. Before Zionism, Hebrew was associated with religious writings.

One important factor that Kanafani writes about which is a recurring theme, is that Zionism was born in times of reprieve rather than oppression.

The book lists times of reprieve for the Jewish people throughout the centuries across the world, noting that at different times, several countries were considered a haven for Jews but that privileged Jews refused integration, thus creating Jewish superiority over the privileged.

In literature, this influence reared its head as Zionists opposed or endorsed literary works. Maria Edgeworth’s novel Harrington, for example, was criticised as it promoted integration.

Other works by Benjamin Disraeli and George Sand contributed to the spread of Zionist propaganda. Disraeli’s novel, The Wondrous Tale of Alroy, depicted a Zionist hero intent on “reclaiming Jerusalem”, 50 years before the official establishment of Zionism as a political ideology.

Eliot’s novel, Daniel Deronda, established the Zionist hero as a protagonist in English literature and contributed to an increase in the publication of Zionist literature.

The idealisation of a Jewish homeland was made popular in literature before becoming mainstream propaganda in political Zionism.

Ghassan Kanafani’s assessment

The figure of “the wandering Jew”, popular in literature, was also used to impart the colonial ideology that by colonising Palestine, Jewish people would no longer face persecution.

While the myth itself is antisemitic, Zionism incorporated it to further justify its colonisation plans, which depicted the future Jewish state as both ideal and a fulfilment of an alleged right.

Zionist literature, Kanafani writes, sought to “mobilise Jews by creating a global environment sympathetic to the Zionist cause and, on the other hand, to obliterate all obstacles in the way of this coordinated propaganda campaign.”

The literature, Kanafani writes, was under no obligation to prove facts. “The Zionist novel does not merely exaggerate the facts; it invents them,” Kanafani asserts, noting that Zionism relied on earlier colonial conquests as justification for its own.

While protagonists in Zionist literature transcend from infallible to absolute superiority, the non-Jewish are either depicted as lesser people, or else eliminated from the narrative – a political practice that Palestinians have experienced for decades. After World War II, the Zionist rationalisation for colonising Palestine was related to the Holocaust.

While noting that Jews living in Palestine before 1948 did not blame Palestinians for the holocaust, Kanafani calls this differentiation from political Zionism the “bare minimum of objectivity”.

While Zionist literature post-1967 called for colonial expansion in Palestine, Kanafani notes that institutions such as the Nobel Prize for Literature also pandered to the Zionist narrative, thus showing a connection between the Zionist novel and Western political thought.

Ghassan Kanafani’s assessment of Zionist literature portrays how influential and entrenched the colonial ideology was before its actual implementation, and how this was rationalised to the extent that the colonisation of Palestine is now normalised.

An important read, On Zionist Literature, is an invitation to delve into detail, to learn and understand the undertones which, as Salaita writes in the introduction, “The great irony of Zionist literature is that it becomes legible only through rejection of Zionism. Otherwise, that literature presents as a natural occurrence in the modern world.

By Ramona Wadi

Ramona Wadi is an independent researcher, freelance journalist, book reviewer and blogger specialising in the struggle for memory in Chile and Palestine, colonial violence and the manipulation of international law