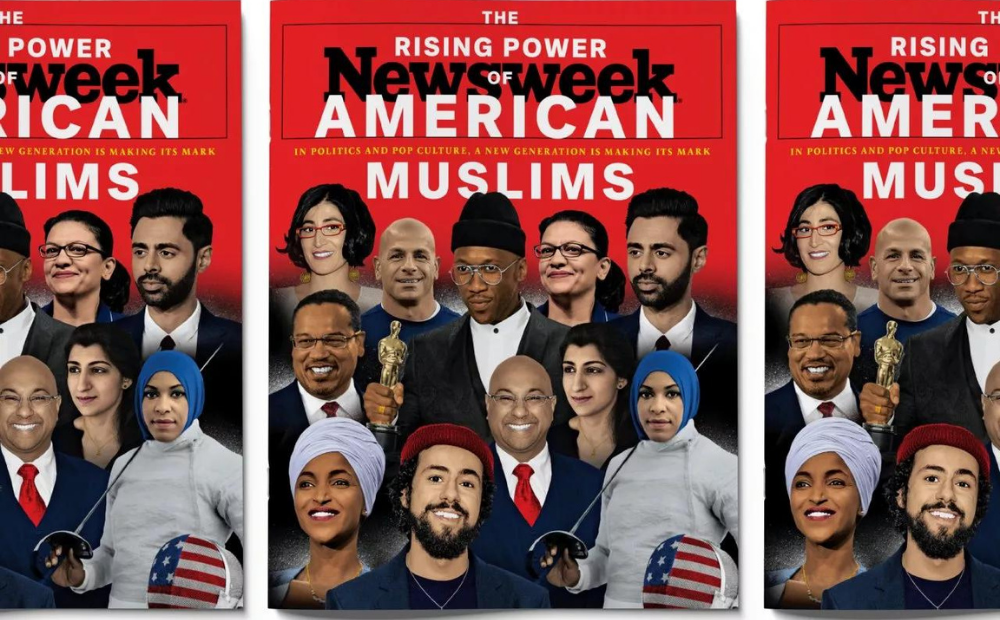

It’s been an impressive 2021 so far for Muslim Americans. The U.S. Senate, that bastion of partisan gridlock, overwhelmingly confirmed the nation’s first Muslims as a federal district court judge and to chair the Federal Trade Commission. Legislatures in five states swore in their first Muslim members, including a nonbinary, queer hijab-wearing representative in, of all places, Oklahoma. Three Detroit suburbs are poised this fall to elect their first Muslim mayors. The New York Jets tapped Robert Saleh as the first Muslim head coach of any American pro sports team. CBS premiered, then renewed The United States of Al, the first broadcast network sitcom with a Muslim lead character. And Riz Ahmed, star of Sound of Metal, became the first Muslim nominated for an Oscar for Best Actor.

“Everywhere I look, I see firsts happening,” says MLB Tonight sportscaster Adnan Virk, who in 2012 became the first on-air Muslim host on ESPN.

As the 20th anniversary of September 11 approaches, the recent rise of many Muslim Americans to positions of power and influence—in Washington and in statehouses, on big screens and small ones, across playing fields and news desks—is a development that few in the U.S. would have predicted two decades ago, Muslims included. In the immediate aftermath of the terrorist attacks by the radical Islamic sect Al-Qaeda, anti-Muslim hate crimes exploded and the ensuing global “war on terror” to root out jihadists created a “climate of discrimination, fear and intolerance,” as one think tank described it, that surrounded people of Islamic faith in this country and lasted for years. Then, just as heightened anti-Muslim sentiment in the U.S. seemed to be subsiding, Donald Trump was elected president in 2016 on an agenda overtly hostile towards Muslims, and revved it up again.

It is the experience of coming of age in this post-9/11 environment, experts say, that drew a new generation of young Muslims to activism, and motivated them to use their voices in political and cultural arenas to debunk misinformation. That they’ve found a receptive audience beyond the Muslim community suggests to some observers that many Americans now understand that the anti-Islamic rhetoric they’ve been served in recent years is based on myths and untrue. As Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison, who in 2007 became the first Muslim sworn in as a member of Congress, tells Newsweek, “The haters have been proven to be liars.”

Maybe. But trend data suggests the answer is not that simple and anti-Islamic sentiment remains a factor 20 years after 9/11. Anti-Muslim hate crimes, for instance, are second only to antisemitic incidents, FBI statistics show. And in a Gallup poll, one-third of Americans, and a full 62 percent of Republicans, said they’d never vote for a Muslim candidate for president, by far the least support for people of any religion in the survey.

Anti-Islamic sentiment remains a factor 20 years after 9/11. President Donald Trump’s ban on travel from seven Muslim-majority countries didn’t help (here, protestors make their feeling about the ban known). JACK TAYLOR/GETTY

Is the recent rise of Muslim Americans to positions of prominence a temporary surge forged during the backlash of the Trump era or a permanent change in American consciousness? Are the constant, often viciously personal attacks on Representatives Ilhan Omar of Minnesota and Rashida Tlaib of Michigan—the most famous Muslims in American politics as well as two of the nation’s most strident progressives—a last gasp of Islamophobia or proof that, in some quarters at least, it’s never going away? If, in fact, the political and cultural shift toward Muslims has staying power, what will the impact be?

The answers are still unfolding. “Muslims are becoming more a part of the American tapestry, but they are still a marginalized group,” says political scientist Youssef Chouhoud of Christopher Newport University in Newport News, Virginia. “The question now is, OK, so you have these Muslims in public office, in the public eye, on commercials, on TV shows. But does it stick? That’s TBD.”

Identity Forged in Adversity

When the attacks by Al-Qaeda occurred 20 years ago, the makeup of the Muslim community in the U.S. was much different than it is today: significantly smaller, older, more conservative, less organized, and made up of more Black Americans and far fewer recent immigrants.

In 2001, roughly 1 million Muslims lived in the U.S., according to the Association of Religious Data Archives, versus 3.5 million recently. As a group, they formed a solid Republican voting bloc, with the immigrant community in particular drawn to the GOP’s messages of self-reliance, small government and conservative social policies on issues like abortion and gay rights. George W. Bush won 72 percent of Muslim votes in 2000, according to the Council on American Islamic Relations, or CAIR; other polls put the figure lower but still showed a big GOP tilt. After 9/11 that support plummeted, with just 7 percent backing Bush in his 2004 face-off with Democrat John Kerry.

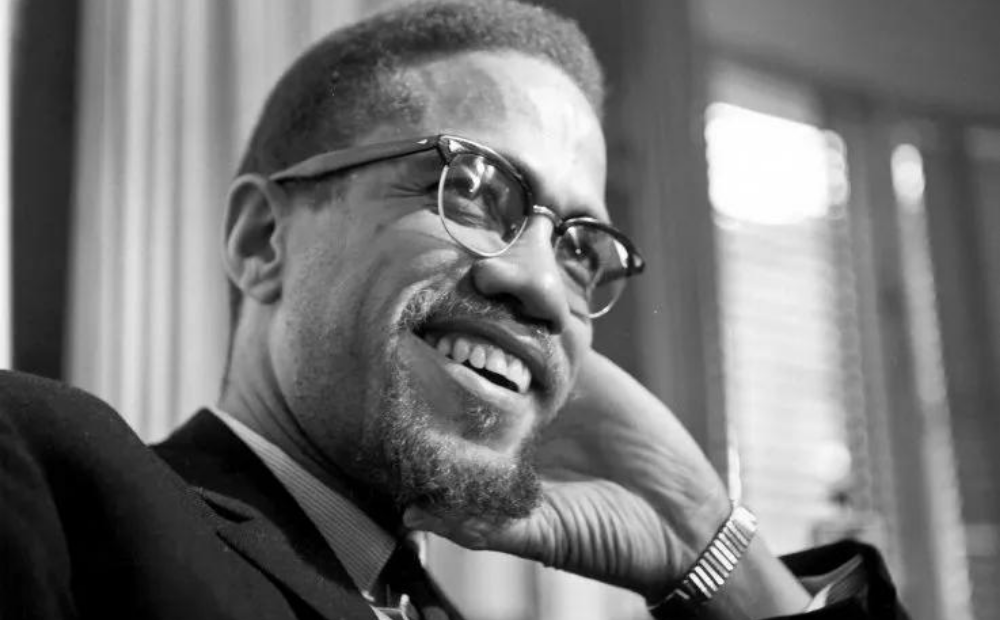

Party affiliation wasn’t the only shift among Muslims in the U.S. in the post-9/11 years. Before the attacks, Muslim Americans seldom saw themselves as a single community bound by a common faith as much as a disparate collection of distinct ethnic groups—Iranian, Iraqi, Syrian, Pakistani and Egyptian among many others—that kept to and fended for themselves, says Niloofar Haeri, chair of Islamic Studies in the anthropology department at Johns Hopkins University. The other large bloc of Muslims in the country were Black Americans who saw the Islam of Malcolm X and boxer Muhammad Ali as both a religion and a political identity used to advocate for the poor and marginalized. That application of the faith, says Haeri, unsettled many immigrant Muslims who came to the U.S. to escape theocracies.

Many Black Americans saw the Islam of Malcolm X (pictured here) and boxer Muhammad Ali as both a religion and a political identity used to advocate for the poor and marginalized. MICHAEL OCHS ARCHIVES/GETTY

Then came the ferocious backlash after the September 11 attacks, marked by a wave of physical and verbal assaults on Muslims and anyone who “looked” Muslim. According to the FBI, there were 28 reports of anti-Muslim hate crimes in 2000; in 2001, that number had climbed to nearly 500. Although then-President George W. Bush had initially urged people not to take out their fear and anger Muslim Americans, his administration later went on to surveil mosques and college Muslim organizations looking for terrorists and invaded Iraq in 2003 on later-debunked claims of involvement with Al-Qaeda and plans to build weapons of mass destruction. Many Christian religious leaders during this period made harsh anti-Islamic remarks as well.

Conservative politicians also spent several campaign cycles in the post-9/11 period ginning up public fear that Muslims wanted to impose Sharia in America—that is, turn religious strictures of Islam into laws akin to those of some Middle Eastern theocracies. “For a while Republicans were all about banning Sharia law, which doesn’t exist anywhere in America that I’m aware of,” Ellison says. “In another way, every Muslim does ‘Sharia law’ every day. When I pray, that’s Sharia. When I fast for Ramadan, that’s Sharia. When I don’t eat pork, that’s Sharia. And these are the people who say they defend religious freedom.”

All of this stoked fear of unwarranted reprisals among Muslim Americans and helped forge a generation of young activists who are now winning political office from city council to Congress, Chouhoud says. By 2007, 84 percent of 12- to 18-year-old Muslim Americans said they had experienced at least one act of anti-Islamic discrimination in the prior year, a New York University study found. In 2009, more than 82 percent of Muslims in the U.S. reported feeling unsafe, an Adelphi University survey found.

Muslim Americans faced a choice: Grin and bear it or band together and respond, Haeri says. “One of the most consequential changes that happened in various Muslim communities post-9/11 was that those Muslims who were not religious and did not identify as Muslim before 9/11 were suddenly being treated as Muslims whether they wanted to be or not and were asked questions about Islam,” Haeri recalls. “Muslim communities filled with newly self-identifying Muslims. There was a lot of soul searching: Why are we shunning this heritage entirely?”

Meanwhile, more religious Muslim Americans, especially the ones who fled autocratic regimes and failed economies, were baffled over questions about their patriotism. “We had to redefine ourselves and push back against injustice—from our country, from the government, from the media, from popular culture,” says Nihad Awad, co-founder and executive director of CAIR. “We felt the pain about 9/11 that everyone felt but more pain than many because we were blamed for what happened—something we had nothing to do with.”

Adversity fused a far-flung gaggle of nationalities into a coalition of necessity, says Democratic Representative Andre Carson of Indiana, who in 2008 became the second Muslim elected Congress. “This role was paved decades ago by the indigenous African-American Muslim community, but 9/11 allowed the immigrant Muslim community to see that the African-American Muslim community was right all along in calling out racial injustices, calling out governmental excess as it relates to violations of civil liberties and spying on fellow U.S. citizens,” says Carson, who is Black.

At the same time, throughout the Bush and Obama years, the pace of immigration to the U.S. from Muslim-majority nations in the Middle East, Asia and Africa surged. Between 2002 and 2016, the number of Muslim refugees accepted into U.S. rose 627 percent—from about 6,000 a year to almost 40,000—which, along with the highest birth rate of any religious group, caused the sharp increase in the Muslim population. The influx has since stopped, as the Trump administration cut the number of refugees accepted into the U.S. to an all-time low of fewer than 12,000 in total, almost all of whom were Christian, according to State Department data.

The number of mosques in the U.S. has more than doubled, to 2,769, since 2000. Here, an outdoor prayer event at Masjid Aqsa-Salam mosque, Manhattan’s oldest West African mosque. SPENCER PLATT/GETTY

“The age-old pattern of immigrants achieving financial success and moving away from cities seems to be repeating itself in the American Muslim community,” ISPU notes.

By the election of Trump, who as a candidate in 2015 called for a “total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States,” the American Muslim community was bigger, brasher and uniformly unwilling to roll over. Indeed, observes MSNBC anchor Ali Velshi, Trump’s effort to ostracize Muslims, and a subsequent rise in anti-Muslim rhetoric and hate crimes to levels not seen since 2001, lit a spark.

“Something is happening right now,” says Velshi, who is believed to be the first Muslim to helm a cable network news program. “It feels like a flourishing of Muslims across industries and across platforms.”

Running While Muslim

The arc of Sadaf Jaffer’s adult life—from college freshman at Georgetown during 9/11 to the nation’s first female Muslim mayor in 2019—offers a useful road map of what has happened to Muslims in U.S. politics over the past two decades and, particularly, recently.

The 38-year-old, who was born in Chicago to immigrants from Pakistan and Yemen, had planned to be a U.S. diplomat and interned at both the State Department and the Marine Corps. But she became increasingly distressed by the anti-Islam sentiment rising across the U.S. and, in 2007, shifted her focus, enrolling at Harvard to pursue a doctorate in philosophy focused on Islamic cultures in South Asia. Her goal: “Understanding Muslim societies better so I could teach about Muslim societies in their complexity.”

By 2017, she was a professor at Princeton University so alarmed by the election of Donald Trump that she decided to go into politics by running for a seat on the Montgomery Township Committee, the governing council for a wealthy, fast-growing New Jersey burg of 24,000 residents about 20 miles north of Trenton. Even on such a small scale, the notion terrified her family. “My parents told me, ‘Shouldn’t we lie low and not draw attention to ourselves right now?’ but I felt like if we don’t stand up for our rights now, who’s to say that we’ll even have rights moving forward,” Jaffer says.

Jaffer won that seat and, in 2019, was elevated to mayor. Her status as the nation’s first female Muslim mayor, she says, was blared in foreboding tones across pro-Trump news sites and Twitter. “That caused an avalanche of hate mail—violent ones, too, about how all of us should be removed from the planet,” she says.

It didn’t deter her from seeking higher office. This June, she won the Democratic nomination for a seat in the New Jersey Assembly; if she wins this fall, she’ll be the first Muslim (and first Asian American) in the Garden State’s legislature. She is bracing for some anti-Muslim sentiment but also views her campaigns as a chance to debunk constituents’ misconceptions about Islam.

“Those person-to-person connections are really important,” she says. “They’re about getting to know people as human beings.”

If Jaffer wins, she’ll follow on the success in the 2020 election that brought the first Muslim legislators to capitols of Delaware, Oklahoma, Colorado, Florida and Wisconsin, and the first re-election of Omar and Tlaib. There are other firsts likely to come this fall too; the top vote-getters in the August primaries for mayor of Detroit suburbs Dearborn, Dearborn Heights and Hamtramck—enclaves with large Muslim populations—were all Muslims.

U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi administers the oath of office to members earlier this year, including Representatives Andre Carson, Ilhan Omar and Rashida Tlaib, three of only four Muslims who have served in Congress. ERIN SCOTT/GETTY

In all, a record 170 Muslim candidates were on ballots in 28 states in 2020, up from 57 in 2018, and 62 of them won. Exit polling showed that more than 1 million Muslims voted last year, also a record.

“When Trump won, it was a wake-up call for the community,” says Wa’el Alzayat, the CEO of Emgage, an organization promoting civic engagement among Muslim American communities.

Also notable: Almost all of these winners are Millennials; Tlaib, at 45 and slightly older than that cohort, is an exception. And most of these Muslim politicans report being the target of some form of anti-Islam sentiment while running.

“They sent out emails connecting me with Ilhan Omar and accusing all the Muslim candidates running across the country of being Islamist or Jihadists,” says Delaware state Representative Madinah Wilson-Anton, 27, who ousted a 20-year Democratic incumbent in 2020 to become her chamber’s first Muslim. “But it wasn’t like, you know, I was door knocking and someone was like, go back to your country. Most of the time, negative responses to me were just partisan.”

Wilson-Anton is not the only Muslim candidate whose religion is used by opponents as grounds to call their qualifications for office into question. In June, GOP Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia sent a fundraising email attacking Omar as a “terrorist-supporting member of the Jihad Squad.” Sam Rasoul, the first Muslim to run for lieutenant governor in Virginia, was asked in May by a debate moderator whether he could reassure voters he would “represent all of them, regardless of faith or beliefs.” And Joe Biden‘s nominee for deputy administrator of the Small Business Administration, health care executive Dilawar Syed, is in confirmation limbo after two GOP senators objected to the fact that he is on the board of Emgage, the Muslim nonprofit. (He says he’ll resign if confirmed.)

In each of these recent cases, though, a broad spectrum from various religious and ideological groups have joined Muslims to object to how the candidates are being treated. An opponent of Rasoul’s, for instant, lambasted the debate moderator from the stage for asking the question and social media scorn was so swift that an anchor for the TV station, WJLA, apologized that night on the air. In Syed’s case, several Jewish groups are rallying to his side.

“Overall,” says Emgage CEO Alzayat, “things are moving in the right direction.”

A Growing Impact

Democratic Representatives Rashida Tlaib of Michigan (left) and Ilhan Omar of Minnesota are considered inspirational trailblazers by many within the American Islamic community. TOM WILLIAMS/GETTY

Virtually every Muslim elected to state legislatures—and all four who have ever been elected to Congress—are progressive Democrats; Carson, the Indiana congressman, was among the first elected officials to endorse Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, a Democratic Socialist, for the 2016 Democratic presidential nomination. Sanders held firm to that support four years later; a CAIR survey in February 2020 found 39 percent of Muslim Democrats supported Sanders versus 27 percent for Biden. For many Americans, this alignment defies well-worn stereotypes about Muslims as extreme social conservatives who would not support a pro-choice, pro-LGBTQ Jewish candidate.

Yet the Omar-Tlaib approach is offensive and troubling for some politically conservative Muslims, who object to what they say is an underlying message that Muslims are badly-treated victims of bias. “The experience of American Muslims is one that’s overwhelmingly positive,” says Omar Qudrat, 40, of California who in 2018 was the first Muslim to win the GOP nomination for a seat in Congress. (He lost by 23 points.) “Many of us reject the victimhood narrative. Do we have problems? Absolutely. But it would be tragic for any young American Muslim to believe all they amount to is being a victim of this great country.”

Qudrat and prominent Muslim conservative Zuhdi Jasser defend Trump’s policies as being in the interest of national security and praise him for brokering treaties between Israel and Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates. “I’m not embarrassed of my faith,” says Jasser, a Phoenix physician appointed by Republican Senator Mitch McConnell in 2012 to the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom. “But I understand the mindset of a country that was attacked. Those wounds are still very deep.”

There is an audience for this view: Trump modestly increased his share of the Muslim vote in 2020 to 17 percent from 13 percent in 2016, CAIR reports.

“Muslims are still a relatively socially conservative population,” Chouhoud says. “Certain values and priorities do overlap between Muslims and Republicans. It’s just that there’s the sense that there is no place for Muslims within the Republican Party.”

Jasser maintains the GOP is not as anti-Muslim as progressives believe, citing the confirmations earlier this summer of Lina Khan to chair the FTC and Judge Zahid Quraishi to the federal bench, by wide bipartisan margins. Awad, of CAIR, counters by citing Republican opposition to other Muslims nominated by Biden for positions within the administration, such as Reema Dudin as deputy director of the White House Office of Legislative Affairs, and the long GOP-led delay on Syed’s bid for an SBA post.

“To dismiss the rest of the Muslim community’s concerns about discrimination, they must be living on the moon,” Awad says. “I have not met a Muslim since 9/11 who has not experienced some form of discrimination.”

Alzayat of Emgage, for one, hopes the GOP does, in fact, become more hospitable. “There will come a day when we have Muslim Republicans running, Muslim Democrats running, Muslim independents running, and they can have healthy disagreements about policies,” Alzayat says. “That would be good for the community and good for democracy.”

The Stars and the Crescent

This moment of ascendance for American Muslims is not only about political achievements. Popular culture, too, is seeing a sharp increase in Muslim representation, and the two trends feed each other. Movies and television offer familiarity that helps fuel acceptance, allowing many non-Muslim Americans who don’t personally know anyone who practices Islam to see Muslim characters woven into the fabric of everyday life.

“It’s an opportunity to create greater empathy for and less prejudice toward Muslims off-screen,” says Arij Mikati of Pillars Fund, a Muslim philanthropy that next year will award $25,000 grants to 10 Muslim TV or movie storytellers.

Among those helping to drive this new level of cultural visibility: Ramy Youssef, who won a Golden Globe and a Peabody Award in 2020 for Ramy, a half-hour Hulu dramedy about a first-generation Muslim American millennial struggling with his faith. Also in the cast for the show’s second season was Mahershala Ali, the first Muslim actor to win an Academy Award, for his supporting roles in Moonlight (2016) and Green Book (2018). Disney+ is due this fall to drop Ms. Marvel, introducing Marvel’s first Muslim superhero, a shapeshifting, bubble-gum-chewing Pakistani-American teen from New Jersey. And there are past and present recent series like Patriot Act with Hasan Minhaj and United States of Al, a CBS sitcom about a U.S. war veteran who helps his Afghan interpreter move to Ohio.

The Netflix series “Patriot Act with Hasan Minhaj” is one of a number of shows that helped to bring Muslim actors and storytellers a new level of cultural visibility. MATT DOYLE/GETTY

Jaffer, the Montgomery Township mayor, says she’s also noticed greater Muslim visibility on kids’ shows like Sesame Street and Peg Plus Cat, and it’s extended to her daughter’s first-grade classroom, where the teacher this spring read a book about Ramadan to students. “Those things seem like little victories, that our celebrations are being recognized as part of America,'” she says. “It’s nice, because as a child, I had to explain everything. Just imagine asking a six-year-old to answer, ‘What is Christmas?'”

Some Muslim actors and celebrities say they try to advance the ball, talking openly about their faith and cultural identity when asked—or not asked. Adnan Virk, while still at ESPN in 2016, recalls being asked to help anchor coverage after boxer Muhammad Ali died. “One of our producers called and said, ‘Hey, we don’t know anything about Islamic funerals. Could you come in?'” Virk recalls. “That made sense. They wouldn’t know. Open casket, closed casket? What prayers are they reciting? Why is he draped in white? That was a cool moment.”

Comic Negin Farsad, a frequent panelist on the NPR quiz show Wait Wait…Don’t Tell Me!, says she takes “any occasion I can when it fits organically in the joke to make mention of being Muslim. I do that to let people know that one of their favorite radio comedy shows has a Muzz on it and it’s cool.”

And MSNBC’s Velshi says he intentionally tries to bring on guests and experts who are Muslims and of other marginalized communities to talk about topics unrelated to their identities. “It’s the simplest thing in the world to do to break down barriers, to cause people to open their minds,” Velshi says. “I want my roster of guests to look like the full breadth of America. Familiarity breeds understanding.”

But while there are undeniably more Muslims in higher visibility and breakthrough roles, experts in and outside of the American Islamic community note that the numbers and depictions still don’t come close to fair representation. A USC Annenberg study this June of 200 popular global movies from 2017 to 2019 found that just 1.1 percent of the speaking characters in U.S. films and 1.6 percent overall were Muslim, still frequently stereotyped as outsiders, threatening or subservient, particularly to white characters.

“More than half of the primary and secondary Muslim characters were immigrants, migrants, or refugees, which consistently rendered Muslims as ‘foreign,'” says Al-Baab Khan, one of the study authors. “Film audiences only see a narrow portrait of this community, rather than viewing Muslims as they are: business owners, friends and neighbors whose presence is part of modern life.”

A Long Road Ahead

The challenges Muslim Americans face in popular culture in many ways mirror the political environment: The gains are real, increasingly visible and more prominent, but for now at least, still relatively modest—and, Muslim activists worry, too easily at risk of being erased.

They point out, for instance, that there’s never been a Muslim in the U.S. Senate, elected as governor or appointed to a Cabinet position. Another major terrorist attack involving extremist Muslims, a successful White House comeback for Trump or the election of a similarly-minded candidate could once again sour public opinion or create new dangers.

“Trump was able to capitalize on bigotry, on ignorance and racism, on fear,” said CAIR’s Awad. “He mobilized it, weaponized it, made it official. His impact is still with us. And he might come back.”

Still, the progress thus far has Muslim leaders cautiously optimistic and thirsting for more. Haeri hopes to see more taught in schools about Islam’s history, noting the contributions of Muslim scientists and artists are absent from the education of most American children. Carson, the Indiana congressman, looks forward to the day he can donate to the first Muslim to run for president. Farsad just wants better roles to play. “I’m both ashamed and unashamed to admit that I have auditioned for the wife of a terrorist,” she says. “That’s what was available.”

“We’ve been so underrepresented for so long, we’re just working to even out the odds,” Emgage’s Alazayat says. “The question is not, ‘Wow, look at how much we’ve done.’ We should expect more.”