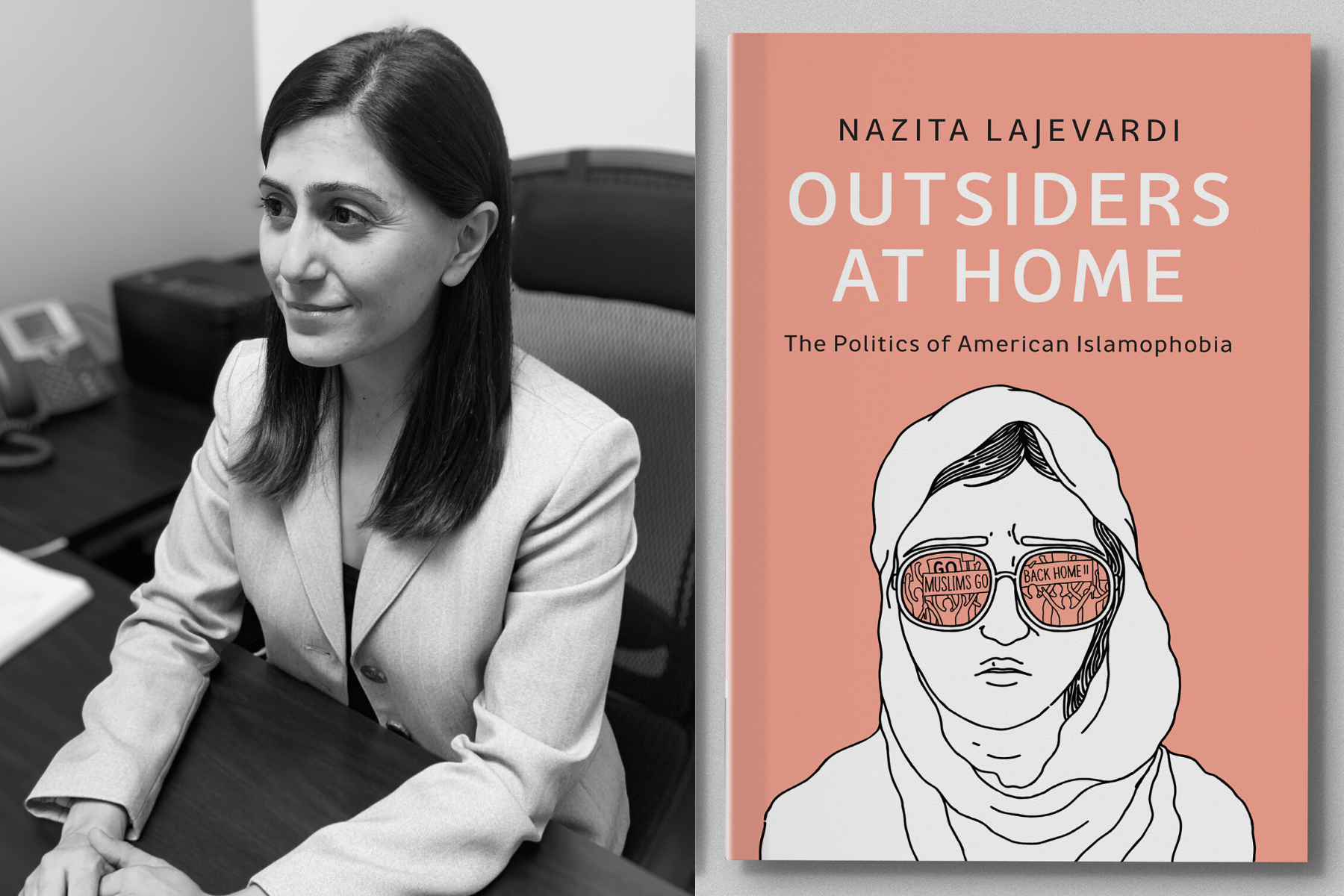

Political science scholar explores the status of Muslim Americans in American democracy

“At 14 years old, I learned that membership in the United States is not permanent,” Nazita Lajevardi, Ph.D., J.D., wrote in Outsiders at Home: The Politics of American Islamophobia (Cambridge University Press, 2020). In the aftermath of Sept. 11, 2001, this daughter of Iranian immigrants saw Muslim women remove their hijabs and Muslim families put American flag stickers on their cars. “My community immediately camouflaged as they waited for the heightened scrutiny on us to dissipate,” she wrote.

In the months and years that followed, the spotlight on Muslim Americans intensified with the war in Afghanistan, the U.S. invasion of Iraq and President George W. Bush’s declaration of the “Axis of Evil.” While Lajevardi and her friends worried about prom and college applications, they overheard their parents whisper about buying property abroad and moving to escape “the rising tide of harassment and discrimination. We heard … and we understood that despite having felt ‘at home,’ we were never really welcome.”

Since then, the stigmatism of Muslims has grown in America with the implementation of numerous surveillance programs targeting Muslim communities, the rise of ISIS, the prolonged detention of Middle Eastern citizens in the U.S., the pervasive anti-Muslim rhetoric of candidates in the 2016 and 2018 campaign seasons, and President Donald Trump’s travel ban on majority Muslim countries, she wrote.

In an interview last week, the Michigan State University assistant professor explained how her research has validated the anxieties she felt growing up as a Muslim American. “The totality of the evidence suggests that the exclusion I was sensing is in fact real and that it is far more pervasive than I had thought.”

Growing up Muslim American

Lajevardi grew up in a “somewhat religious” household in Orange County, California. “I went to Sunday school where nobody wore a hijab. It was more about spirituality, Sufism and mysticism,” she said. Most of her high school friends were Christian, Hindu or Catholic.

“There are not many Muslims who grew up here as the children of immigrants, navigating issues like ‘my friends are drinking and wearing short skirts, and my mom says I can’t do that and I can’t have a boyfriend,’” Lajevardi said. “They had to ask themselves, ‘Do I feel that faith or is that my parents’ faith? How do I adapt?’

“Now that I am a researcher, I understand. We, the non-Black children of immigrants, were such a small subset (about 25%) of the Muslim population in America.” And there are only eight states where Muslims compose more than 100,000 residents.

Her sense of isolation changed when Lajevardi went to Boston College. “For the first time in my life, all my friends were Muslims. During Ramadan, the university had iftars for us every night. I went to jumaa prayer with my friends. When I had to figure out what it means to go to frat parties and practice Islam, I got to navigate it with my Muslim friends. I felt so uniquely supported in a way I never had before,” she said.

After her first year, Lajevardi’s parents couldn’t afford to send her back. She transferred to a local community college. But a decision she made in Boston—to fast every Friday and go to jumaa prayer— “grounded me in my faith,” she said.

Then “God opened a door I didn’t see coming,” Lajevardi said about her acceptance to the University of California, Los Angeles on a full scholarship. “God had equipped me that first year of school with all the tools of my faith, and then He had this path for me.”

At the University of California, Los Angeles, she found another community of Muslim friends and continued to grow as a Muslim. “I have a very deep faith,” said Lajevardi, who doesn’t wear a hijab, but has been to Umraa four times.

“God has done everything for me. Everything. None of this is me,” she said. Holding up her book Outsiders at Home, Lajevardi said, “I feel with this book, I’m so blessed that God wanted to do something in this world and I had a chance to do it.”

From law school to research

After graduating magna cum laude in political science and French, Lajevardi went to law school at the University of San Francisco. While there, she researched Section 215 of the Patriot Act, which authorized the use of court orders requiring third parties like telephone companies to provide any records deemed relevant to international terrorism. Use of the Patriot Act has often been criticized for abuse and overreach.

“I was given space to see how different courts had been interpreting it and applying it,” she said. “For the first time, I saw the devastating toll just one small section of the Patriot Act had taken on Muslim lives here in the United States. And for me that was profound. It was perhaps the first time in my life this crazy reality I felt internally in myself, and in my family and community was actually validated in the outside world.”

Meanwhile, Lajevardi accepted a job to become an assistant district attorney in Sacramento County and was studying for the bar. “But something kept nagging at me,” she said. She passed the bar, but then declined the job and opted to pursue doctoral studies at the University of California, San Diego instead.

“It’s funny how God opens doors for you. Practically no one was studying Muslims,” she said. “Nobody thought these issues were worth exploring.”

Investigating U.S. Islamophobia

Lajevardi began her academic career in 2017 in Sweden at Uppsala University. As a researcher on the CONPOL project, she explored how individuals’ involvement in politics is shaped by their social contexts. In 2018, she joined the political science department at Michigan State University, where she also serves as affiliated faculty in MSU’s Muslim Studies Program and at the MSU College of Law.

A prolific researcher, since 2017, Lajevardi has produced 17 academic journal articles, four book chapters, and won numerous grants. She co-authored the book Race and Representative Bureaucracy in American Policing in 2017 and co-edited Understanding Muslim Political Life in America: Contested Citizenship in the Twenty-First Century in 2018.

In May 2020, Cambridge University Press published Lajevardi’s comprehensive examination of discrimination against Muslim Americans today, Outsiders at Home. Her findings provide overwhelming empirical evidence of strong negative bias against Muslim Americans by the American public, media and political elites. This bias has “stark implications for the quality of Muslim American participation and representation in American democracy,” she said.

Lajevardi’s last work is attracting attention in this election year. She was recently interviewed on TYT’s The Conversation and The Damage Report, Michigan Radio (NPR) and Religion News Service.

A Q & A with author, attorney and scholar Nazita Lajevardi

How bad is Islamophobia in America?

It is far more pervasive than I had sensed. Part of that is that Muslims reside in such select states so the experiences and information we have as a collective doesn’t approach, even closely, where the country is and has been. In many ways, we have been shielded from it. So, if it felt terrible, we don’t even know the half of it. It is rampant and incredibly powerful, affecting the lives of millions of people.

What is the status of American Muslims in American democracy?

Negative attitudes towards Muslim Americans are pervasive and these attitudes matter for vote choice and policy preferences.

Did you find anything that surprised you?

Many of us felt, during the Obama years and after, that every time you turned on the news it was about Muslims. By putting numbers to it, we see that, in fact, the media is portraying Muslims at high rates, and when it does, that coverage is negative and is impacting American attitudes toward Muslims. On top of that, to show that portrayals of foreign groups matter for attitudes toward a domestic one, that people don’t take time to distinguish, is another big finding.

Did you find anything that gives you hope?

Now we are no longer talking about issue-based politics. Gone are the days when our parents could come out and say no to gay marriage or yes on two-state solution. All of that is out of the window. We are no longer thinking about politics on these issues. We can’t afford to as a community. All we can do is ally ourselves on one side or another. It gives me hope that Muslim Americans have found ways to create coalitions with other racialized groups and the progressive political agenda.

Is there anything you want to say to the Wisconsin Muslim community?

I want to encourage them to work with scholars studying Muslim Americans, especially those of us who are from the community, who are spending our lives trying to help in the ways we can. I understand that they are afraid of being surveyed because they have been tricked before and are afraid of sharing information with law enforcement agencies under false pretenses. But I believe we are fighting the same fight. Have faith in us.

I would ask them to support scholarship by buying books that support Muslims and sharing them with their family members and friends, writing Amazon reviews. We need clicks, purchases, word of mouth, invitations to the masjids, to give talks to the community. It empowers us as Muslims; it gives us visibility.