Veteran journalist, poet and author Susan Hartman speaks about her new nonfiction book, City of Refugees, Monday at Boswell Books’ virtual World Refugee Day event.

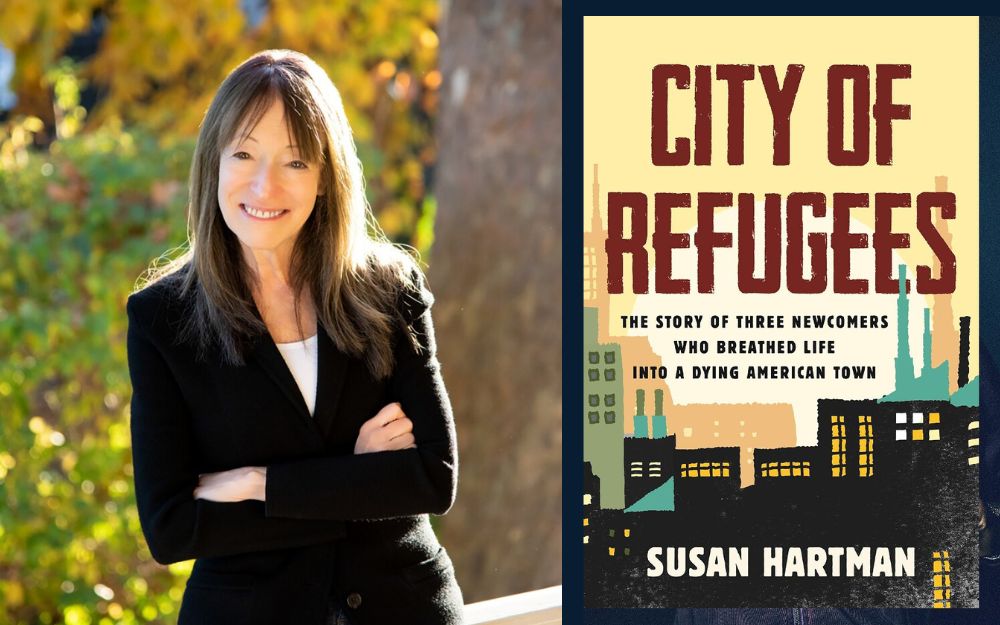

Contrary to the popular belief that refugees drain the economy, the opposite is true. They rebuild and revitalize America’s dying rust belt cities, says journalist Susan Hartman in her new book City of Refugees: The Story of Three Newcomers Who Breathed Life into a Dying American Town, released June 7.

“This is an American tale that everyone should read – the story of three refugees who forged a new life in the Rust Belt,” wrote Pulitzer Prize winning journalist Jake Halpern. “Hartman’s journalistic dedication is nothing short of astounding. She spent eight years following her subjects, and it shows.”

Hartman’s cover stories and profiles have appeared in The New York Times, Christian Science Monitor and Newsday. The author of two books of poetry, she studied at Kirkland College and received an MFA from Columbia University’s School of the Arts, where she now teaches.

She will be in conversation Monday, June 20, at 7 p.m., with Mitch Teich of North Country Public Radio and formerly a producer and host of WUWM’s Lake Effect in a Boswell Books’ virtual event. Hartman and Teich will discuss what her reporting illuminates about the larger canvas of refugee life in America today.

Daniel Goldin, proprietor of Boswell Books, 2559 N. Downer Ave., Milwaukee, said in a telephone interview today, “This a great conversation to host on Monday, World Refugee Day. I read City of Refugees and liked it. We’ve been in discussions with the Milwaukee Muslim Women’s Coalition about refugees.” And Teich, who had been in Milwaukee, is now at a station in Canton, New York, “with Utica, the city referred to in Hartman’s title, in its listening area.”

This special event is cosponsored by Milwaukee Muslim Women’s Coalition and Lutheran Social Services of Wisconsin and Upper Michigan.

Watch her conversation with Mitch Teich.

From her home outside New York City, in a Zoom interview last week with Wisconsin Muslim Journal, Susan Hartman shared what she learned about refugees, Muslims and America by writing City of Refugees.

A little background

Hartman’s book is the product of extensive, immersive reporting on three refugees and their families, and interviews with about 100 other Uticans from all walks of life, including politicians, professors, bartenders, doctors, amateur historians and people who were unemployed. It offers an intimate picture of her subjects as they created new lives in American and spotlights the impact their presence had on an old manufacturing town.

From Fall 2013 to Spring 2021, Hartman followed Sadia from Somalia, Mersiha from Bosnia and Ali from Iraq, and their families, “observing them as they went about their daily lives.” She sat in a corner of a couch or chair in their homes, taking notes in longhand, “getting down every word.” Occasionally, she attended a family event—a wedding or graduation, saw them at work or went along on errands but mostly she visited them at home.

The length and depth of the project – 30 visits over eight years that included hundreds of interviews – gave Hartman new insights into topics she has written about for 35 years, including immigrant communities, the refugee experience and Muslims in America.

This is your first nonfiction book, right? Congratulations! What impact did this project have on your personally?

Yes, it is. I have written two books of poetry and long, in-depth cover stories, but not a full book. It was the greatest project ever. It was a privilege. It was delicious. It was always on my mind. My husband has been listening to stories about Utica for almost a decade every single day.

You explain in your Author’s Note that a college economics professor who knew you often wrote about immigrant communities called and said, ‘Did you know Utica has become a city of refugees?’ How did that tip turn into an 8-year project?

Four days later, I went up with him and he drove me through streets once filled with abandoned houses. Fascinated by how Utica had changed, I kept returning.

My first week reporting, I met three remarkable newcomers. Sadia, a bright, rebellious 15-year-old, answered the door. I’d come to see her mother, who had 11 children and worked at Chobani, the yogurt factory. “Will you save me?” Sadia said, laughing, as she pulled me inside. She’d recently been suspended from high school for getting into a fight with another Somali Bantu girl.

I was also drawn to Ali, an Iraqi interpreter with large reserves of feeling. He worked in Utica’s courts and hospitals but seemed shadowed by war. Mersiha—a Bosnian refugee who ran a bakery out of her home—was a kind of visionary. Her head was buzzing with entrepreneurial ideas.

And Utica, the fourth subject in this story, was remarkably changed. In the 1990s, the neighborhoods were literally on fire and dogs that could attack people were loose in the streets. Gangs were in abandoned houses. Today you see new porches and new roofs on houses that had been falling down. You see children’s sneakers on the porches. It is very heartening. In 2014, I wrote a story about the city’s revitalization for The New York Times.

I didn’t expect to follow my subjects for eight years. But their lives were changing so rapidly—and I kept wanting to see what was next. Instead of just moving on, I kept going back. I knew I was doing something; it wasn’t always apparent it would be a book.

Was it more challenging to write a book than a long cover story?

It was initially overwhelming because I had hundreds of pages of notes. With a cover story, you have a nice, fat folder. (She looked around and laughed.) If you could see my study! I have piles and piles and piles of folders. I’d think, ‘How do I begin? How do I structure it? Once I knew the story, I approached a publisher.

Much of your work, like this book, is about immigrant communities. What attracts you to this subject?

Part of the answer is that is who I see around me in New York, although I have done lots of stories on other things as well. I’m interested in intimate communities and in New York city there are so many around. I started out in 1988 being fascinated by these little girls on my block who were Double Dutch jumpers. They were just there on my stoop.

I saw that New York Times cover story, The Jump Rope Girls 20 Years On (2008). It’s wonderful. But there were lots of things around you in New York. Is there something about you that makes you interested in immigrant communities?

I was raised to just always be curious about different cultures, and different foods. I love to eat. My mom is first generation. Her parents were refugees who fled Poland because of the pogroms, so the immigrant story is familiar to me. Immigrants are very inspiring, how resilient they are and how they function so well as a team.

The three main subjects of your book are Muslim although you met people of other faiths in Utica, like Pri Paw, a Buddhist, who is in your June 3 New York Times cover story. Why did you choose three Muslims for your focus?

As a journalist, there is a kind of chemistry between subject and reporter, especially if you are going to spend a very long time with them. I gravitated to those three people and they happened to be Muslim.”

Had you written about Muslims before?

Yes, I wrote about a Muslim spiritual leader, an amazing woman. She became one of the first female foreign exchange traders in New York’s financial district, working in the private sector before she moved to Long Island and became a Muslim chaplain at Stony Brook University. I also did a story on modern Muslim women on Long Island and how they feel about balancing two worlds. I have visited mosques many times.

For your three main subjects in your new book, how much did their Muslim faith play into their lives?

It was very important to them. Mersiha’s family is very devout. Their faith means so much to them and they pass it on to their children. They are connected to the large Bosnian mosque in Utica, the biggest mosque. They also practice at home.

One of my favorite parts of the book is when, during Ramadan, Mersiha goes to her mother’s grave and has a conversation with her. She does that every year. Hearing her talk about that was just really wonderful to me. It is such a joy and privilege to get to observe very private things.

In the Somali Bantu family, the mother was especially devout and prayed at home five times a day. Sometimes, she would go to a small mosque she belonged to. And Ali, I think as a teenager, he had rejected Arab culture and his faith to some extent. But then, being in America, he rediscovered it and is devout.

Did you learn anything new about Muslims in doing this project?

One thing that was different for me, because I observed so many Ramadan’s over the eight years of this project, I had more of a sense than I ever did before of what it is like from the Muslim perspective. To an outsider, you are likely to think, ‘Wow, it must be so hard and unpleasant to be fasting.’ But the joy these families take in Ramadan was so apparent to me. It was really lovely to see that up close. It was wonderful.

When reporting the recent New York Times piece, we celebrated the 27th meal with Mersiha’s family, they brought food up from their restaurant and had a spectacular feast.

Your books sub-title, “The Story of Three Newcomers Who Breathe Life into a Dying American Town,” presents the position that refugees are good for dying towns. Is that your message?

As a reporter, I don’t go into a story thinking this is what I want to show. No, I just go and explore and see what I find. If you take a look, you’ll see they have breathed new life into that city. They are necessary.

Refugees have sparked a transformation in Utica and other rust belt cities. They work hard, buy cheap houses and fix them up. They open small businesses. I think one reason Utica welcomed refugees is they remembered their grandparents who sold ices on the street. In Utica, it’s now four decades of this slow revitalization.

Of course, not everyone welcomed them and different groups might have been received differently. The Bosnians were widely admired. They came with education, skills and sometimes a little bit of resources. Refugees who come from camps may have a longer, slower trajectory, like the Somali Bantu.

Because Utica had been devastated economically, they appreciated the refugees. There’s this pride in what the city has become and there’s this hope now that now the place will attract younger people, professionals. That’s a nice thing that’s happened recently—young people are coming back. There are more jobs and young people are coming home.

In the book, I write about a couple of guys who opened a café in Brooklyn, then came back to Utica when they heard things were getting better and started a café there. They are happy to be back. Their great grandparents had worked in the mills that closed many years ago.

Will you continue to visit these families?

Yes, I’ve been up since I finished the project and I’m going up next week for a book launch on Saturday, June 18, the day Utica is celebrating World Refugee Day. We are going to have a celebration there.

What hopes do you have for the impact of this book?

It’s been a surprise to me that we have received a very positive response with this story about refugees. We think the media is filled with stories about anti-refugee feelings, but obviously there are also many people who have written to say how admirable these people are. I hope other communities and rust belt cities will see this example realize that refugees are a good thing for a city.

This interview has been edited and condensed from a conversation with Hartman and her Author’s Note and About the Process sections of City of Refugees.