Shawn Muhammad, director of Asha’s Ujima Men’s Program shows his “Male Advocate of the Year” award presented to him at the Office of Community Wellness and Safety’s Love Without Violence Conference.

Milwaukee anti-violence advocate and peace activist Shawn Muhammad said “With Survivors, Always,” the 2025 theme for October’s Domestic Violence Awareness Month, is at the foundation of his agency’s work. But he also gently suggested that there can and should be room in the equation for those who do harm.

“We are focused on the safety of women and children first and foremost,” said Muhammad. “However, you must deal with what we are not saying: that we are here for the perpetrators.”

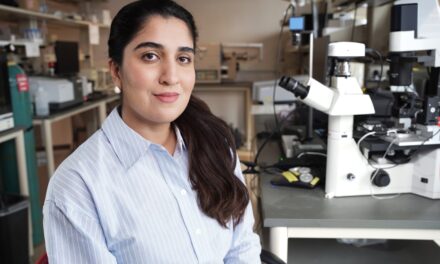

Muhammad retired from Asha Family Services Inc. (Asha) as associate director in 2022 but returned this year after the agency restructured and intensified their community intervention efforts, combined with domestic violence and intimate partner violence services. He is director of Asha’s Ujima Men’s Program and Community Violence Intervention.

Founded in 1988, Asha was Wisconsin’s first culturally specific African American domestic violence victim agency and is recognized as being one of the first in the U.S. It serves domestic abuse survivors, victims of sexual assault, those who have been sex trafficked and perpetrators of abuse.

Muhammad’s 16 years as associate director taught him that a punitive approach alone does not solve the issue. He also learned that domestic violence professionals need to be more inclusive and more creative to address the root causes of violence.

“More than 70 percent of domestic violence victims return to their abusers. We need to take a holistic view in how we deal with domestic violence and that includes attending to the perpetrators as well the victims. I believe every human being can be redeemed—that they can unlearn and change bad behaviors,” said Muhammad, who has a degree in human services with a focus on addiction services.

He said that includes holding abusers accountable but also helping them become a better version of themselves—like he did. Raised on Milwaukee’s North Side by a single mother, herself a domestic violence survivor, Muhammad said he came from a dark place.

Shawn Muhammad addresses youth basketball league about resolving conflict without violence and promotes his Community Code of Conduct.

“I have a shared experience with many of the men I work with and that makes me relatable. Because of where I’ve been, I’m hesitant to harshly judge anyone. After all, it took someone like Louis Farrakhan to put the right words in my ear for me to finally change my life. And if that can happen to me—if I can change—it can happen to anyone.”

Muhammad, a student minister at Muhammad Mosque #3 in Milwaukee and widely known as Brother Shawn, was inspired by Farrakhan at the Million Man March in 1995 in Washington, D.C., but he credits Asha founder and executive director Antonia Norton with leading him to this work, which he said is his calling.

“She has been such a wonderful mentor, and I don’t feel like I’d be here without her guidance. She cultivated a lot of the things that I’m now doing in the community.”

Norton established Asha’s Ujima program, named for the Kwanzaa principle of collective work and responsibility. It uses traditional methodology such as recognizing the characteristics of abusers and addressing the cycle of violence.

“But we also incorporate such things as relaxation techniques. We help men set up responsibility plans to use when they feel triggered. We teach a knowledge of self, helping men to be aware of their triggers and weaknesses so they can rise above them with rational thought.”

A key to his program’s success, he said, is love.

“What we do is effective because my brothers know that I love them. Don’t get me wrong, they are held accountable and sometimes we are using tough love. But if you are coming from a place of love, it is easier to accept.”

Reacting to the recently released End Domestic Abuse Wisconsin Homicide Report 2024, which reveals a record 110 lives lost to domestic violence in the state last year, neither Norton or Muhammad were surprised by the statistic.

“Sadly, this does not surprise me,” Norton said. “What we are witnessing is the convergence of untreated trauma, economic stressors, limited access to culturally responsive services and the ripple effects of the pandemic that continue to strain families and communities.”

Muhammad agreed.

“Some of it is caused by residual violence that can be attributed to the effects of the pandemic, but it also doesn’t surprise me at all given the overall psyche of the American people and the extreme divisiveness we see in society today.”

Both lament the fact that as cases continue to increase, funding is decreasing.

“Asha is a very small agency, and the funding cuts really affects us,” Muhammad said. “The current administration is also attacking DEI [diversity, equity and inclusion] programs, so I feel like our woman-led, culturally specific agency is taking a double hit.”

Brother Muhammad and community members patrolled high-crime neighborhoods this summer as a gun-deterrent effort and to promote the Community Code of Conduct.

Norton noted that smaller, community-rooted programs like Asha, which serve Black, Brown, immigrant and Muslim populations, are the first to feel the cuts.

“The erosion of federal and state funding for victim services has been devastating,” she said. “Programs are closing or operating at reduced capacity just as the need for safety, housing and counseling has intensified. For agencies like ours, it means we must stretch limited resources further; trying to meet complex needs without the infrastructure or workforce to sustain the response.”

Norton is encouraged, however, by what she sees as a growing recognition that domestic violence is not just a private concern but a public health and community safety issue. She also feels heartened by witnessing lives being changed through programs like the Ujima Men’s Program as well as seeing younger advocates, men, faith leaders and survivors themselves stepping forward to be part of the solution.

“Change is possible when we focus on a trauma-informed public health approach, healing and accountability instead of punishment alone,” Norton said, adding that awareness is more important than ever.

“People should understand that domestic violence is not confined to certain neighborhoods or demographics. It’s everywhere, but the impact is not equal. Communities of color often face added barriers: distrust of systems, fear of child welfare involvement and lack of culturally competent services.”

Norton said it is also important to recognize the impact of leaders like Muhammad in Milwaukee.

It’s important that we highlight the courage and leadership of men like Shawn and others who challenge harmful norms and engage men in accountability and healing. Ending domestic violence requires all of us—survivors, advocates, men, faith communities and policymakers—to work together. I have often said that until men say violence against women stops, it won’t.”

If you are experiencing abuse, call the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799-7233.