© Photo

Lila Aryan Photography for the Wisconsin Muslim Journal

© PHOTO NOTE: All the editorial images published here have been posted to the Wisconsin Muslim Journal’s Facebook Page. You may not post, distribute, perform, display, transmit or reproduce in any way any copyrighted material, trademarks, or other proprietary information without obtaining the prior written consent of the owner of such proprietary rights.

The entrance to the Lynden Sculpture Garden is clearly the entrance to an estate, the old-fashioned kind, with gatehouses and discreet, vine-covered gates. Today the gate is open and admission is free. A woman in a pink work shirt approaches my car and says, “More parking through there.” She will turn out to be Polly Morris, executive director of an open-air museum covering 40 acres of parkland and gardens and home to a legendary group of modernist sculptures.

The art was collected by the late Peg Bradley from 1962 until her death in 1978. The place is named for her husband, Milwaukee industrialist Harry Lynde Bradley.

Educational programs, temporary exhibitions, and performances are held here year-round, and today’s HOME Festival will be all of the above. The HOME Festival was scheduled to coincide with World Refugee Day, which is observed on June 20th and is meant to create awareness of the plight of refugees around the world. For many of the refugees, the joy of sharing a beautiful sunny day in a lovely garden was tempered by the knowledge that millions of others did not get the opportunity to share this experience.

This sunny Saturday in June is also a “community-led Free Family Day” and the parking lot is experiencing a traffic jam caused by a yellow bus that brought members of Milwaukee refugee communities here from their city neighborhoods. The Lynden parking lot is unusually full, and carelessly parked cars are making it difficult for the driver to exit the lot.

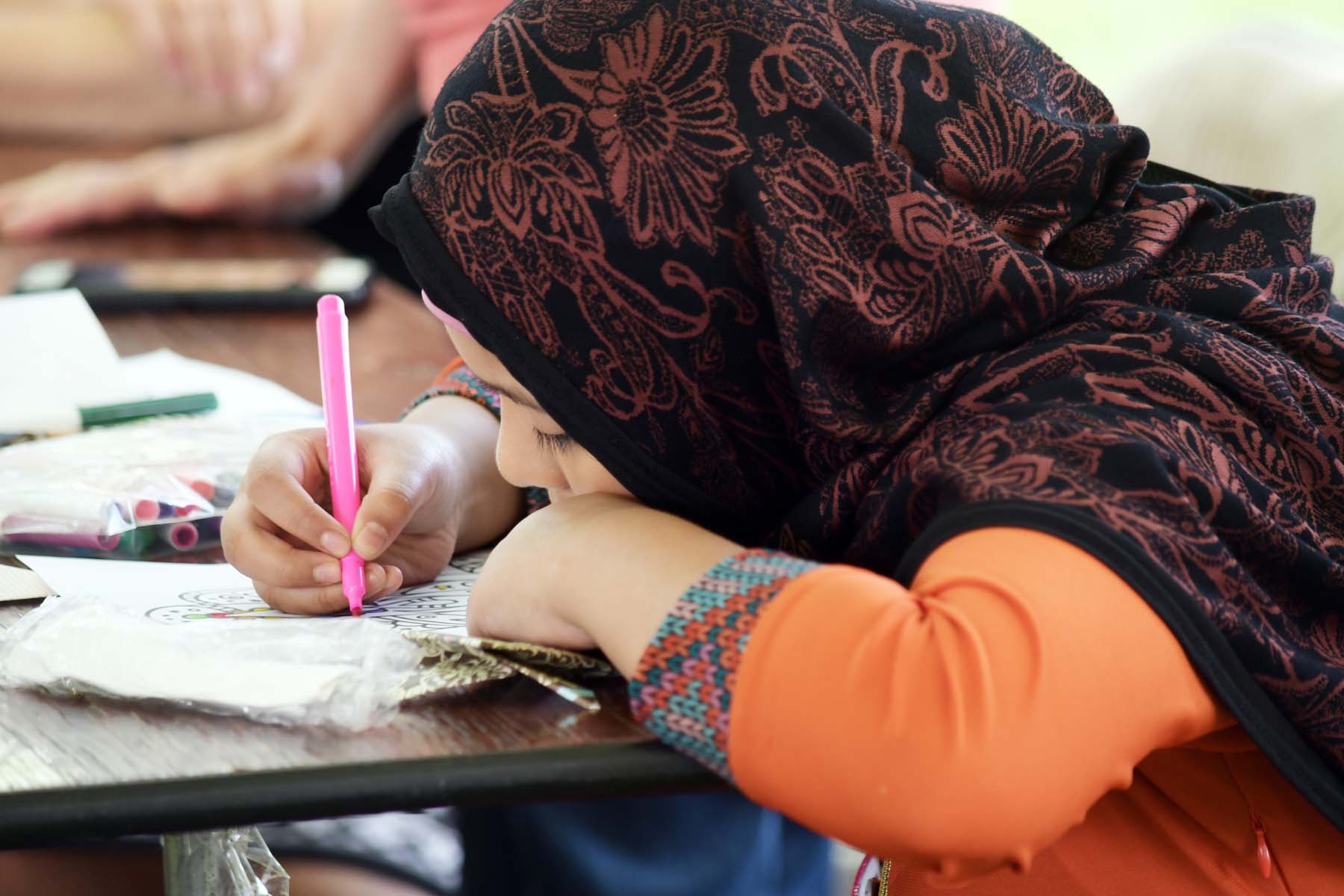

Behind Peg and Harry Bradley’s sprawling former home a party is in progress. A diverse array of ethnic communities and local museum visitors mingle as they dye batik shirts and have their hands decorated with henna art.

You could also eat home-cooked Ethiopian or Malaysian food, browse craft tables, sing, listen to speeches, learn more about different communities by talking to their members, and collect brochures from the service organizations who work with refugees. Event organizers Kim M. Khaira and Rohingya refugee leader Hasinah Begum gathered newly arrived members of Syrian, Ethiopian, Somalian, Rohingya, Burmese, Karen, and Congolese communities for the event.

“We’ve been working with refugee groups for the past three years,” Lynden’s Polly Morris said. “But this is the biggest event of its kind that we’ve held.”

Kim Khaira is a 2019 artist-in-residence at Lynden, and today’s HOME Festival is part of her year-long project, “Pulang Balek,” which, in the Malay language, means, “I am going home too” and includes her more traditional drawing and painting.

Khaira studies henna “as a ritual” practice, along with its origins, and makes her own paste, but part of what drives her to do projects like the festival is the opportunity to be spontaneous, “rather than an art piece that becomes a product you hang on a wall,” Khaira said, gesturing around her and quoting Picasso’s famous remark that, “an artist is a political being.”

At the batiking tables, refugee community members and visitors helped each other use carved stamps dipped in hot wax to make imprints on white cotton and linen items that are later dyed – with the dye color appearing everywhere but the waxed parts. The batik artist and indigo advocate Arianne King Comer supervised the dying, commanding buckets of thick, colorful dyes, including one clearly labeled “Indigo.” On the grass surrounding the tables freshly dyed tee shirts and scarves were laid out to dry.

Also available were representatives from organizations that included Public Allies, the Hanan Refugee Relief Group, the City of Milwaukee Health Department, the Medical College of Wisconsin, the National Council of Jewish Women, Lutheran Social Services, and Catholic Charities. Each group works with different facets of the refugee experience.

Sea Literacy was founded eight years ago by Milwaukee landlord Bob Heffernan, who said that renting affordable housing to refugees made him “a part-time social worker too.” He realized his refugee tenants were not receiving needed services when they asked him to translate their mail. His fledgling organization put an add on a volunteer Web site that contained just four words: “Read to refugee children.” The organization now provides tutoring, mentoring, and cross-cultural literacy training.

Musician Mohammed Hasan played guitar, alternating stage time with groups of women singers who created a pop sound using their voices and a traditional drum.

Janan Najeeb, president of Milwaukee Muslim Women’s Coalition, spoke of her group’s new initiative, “Our Peaceful Home” project to help families learn how to deal with issues caused by trauma experienced during war or in refugee camps. “What is acceptable is based on the practices of Prophet Mohammed – if the Prophet treated his family, women and children, with dignity and respect, then that should be our practice.”

Children ran underfoot, sometimes interacting in creative ways with the sculpture.

Two young people from the Hmong community demonstrated the confidence of the next generation in the American dream. Paul Vang, who along with Ashley Xiong, represented the Hmong-American Women’s Association, said their focus was on “acquiring generational wealth.” Vang explained that though their parents’ generation did the best they could, they “often didn’t have formal education. Starting now is when we cement our place in American society.”

Back in the parking lot, executive director Polly Morris cheerfully tried to keep order among the departing cars. A group of children were turning a sculpture on its concrete base so they could swing on its arms. Morris gave a nod to a young man with a bushy beard, who took off in the direction of the kids swinging from Aldo Calo’s “Orzzontale,” which had temporarily become a roundabout. That day, the Lynden Sculpture Garden was a place for Americans both new and old to be enriched by each other’s company.