Photos by Kamal Moon

University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Arabic Language Program coordinators Fahed Masalkhi, Ph.D., and Khuloud Labanieh, Ph.D., are well-known in Greater Milwaukee’s Muslim community for widely sharing Arabic language and culture.

Ayah Naji, 19, of Oak Creek grew up surrounded by people speaking Arabic. Her father immigrated to the United States from Palestine and her mother grew up in a Palestinian American family in California.

“I could understand and say a few words here or there but I couldn’t carry a conversation,” the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee sophomore in psychology told the Wisconsin Muslim Journal. “For example, my grandmother knows some English but I feel like there’s always a language barrier between us,” she said. “I’m always asking Mom, ‘What did she say?’

“I feel like I struggle more with identifying as Arab or Palestinian because I don’t speak the language fluently,” she said. “The language is a huge tie. The music, the traditions, the culture—it’s all in the language.”

Naji decided to enroll in UWM’s Arabic Language Program.

UWM junior David VandeWettering, 21, of Milwaukee had no connection to Arabic language or culture. The religious studies major wants to read the Quran and a variety of writings from the Middle East in their original language. “Christians and Jews in the Middle East also used Arabic for some of their writings,” he noted.

“I had a decision to make between Arabic and Hebrew. Arabic has a slight edge. It is probably more marketable than Hebrew because more people speak it,” he said.

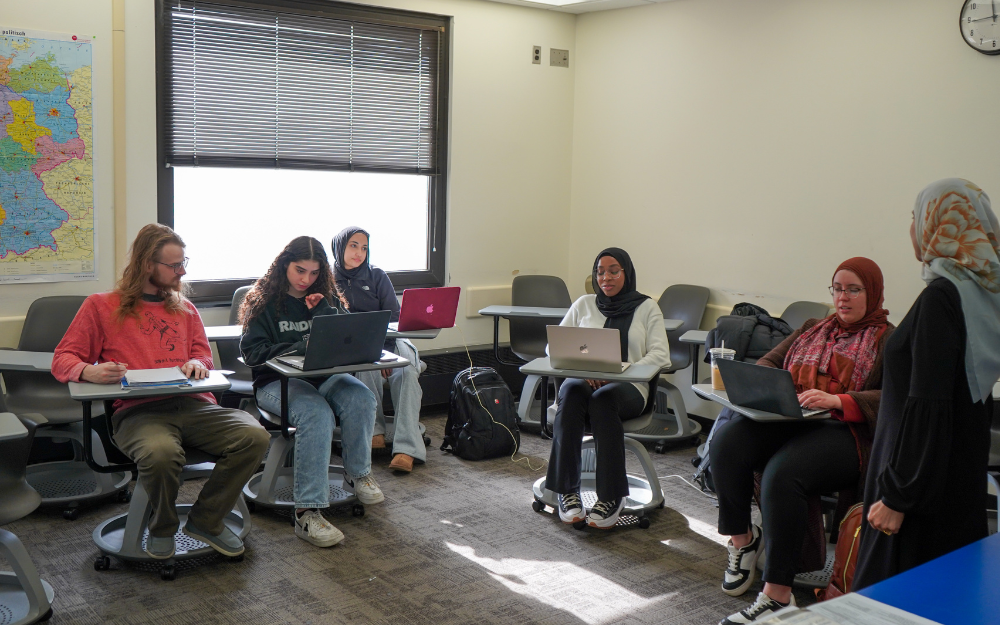

Heritage language learner Ayah Naji (second from left) studies Arabic to better communicate with Arabic-speaking relatives and strengthen her sense of Arabic identity.

More than 400 million people, primarily in the Middle East and North Africa, speak Arabic. It is also the fastest-growing language in the U.S., according to Census data. And as the language of the Quran, Muslims around the world of all nationalities and ethnicities learn to pray and recite the Quran in Arabic.

VandeWettering’s interest in Arabic goes beyond its market value. “You learn so much about Arabic speakers’ faith and culture because they are inextricably linked with the language. The expressions ‘inshallah’ (God willing) and ‘mashallah’ (God has willed something beautiful and good) are interspersed throughout. I think it is really cool how they see God everywhere.

“Learning another’s language can show a deep appreciation of their culture,” he added. “It’s one way human beings can show love to other human beings.

“And just the beauty of the language is something I deeply appreciate and enjoy learning.”

Fahed Masalkhi, Ph.D., plans to develop courses in Quranic Arabic for religion scholars and Muslims. “For Muslims, Arabic is not optional,” he said.

The United Nations celebrates World Arabic Language Day on Dec. 18. Wisconsin Muslim Journal pays tribute to the occasion with a look into UWM’s Arabic Language Program and the Syrian American couple at its helm.

UWM Arabic Language Program coordinators Fahed Masalkhi, Ph.D., and Khuloud Labanieh, Ph.D., have helped UWM create opportunities for a wide range of students—from beginners to native speakers and every level in between—to develop Arabic language skills and cultural competence. The couple are well-known in Greater Milwaukee’s Muslim community for widely sharing Arabic language and culture.

University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee’s Arabic Language Program allows students to earn retro credits for previous knowledge of Arabic.

UWM’s Arabic Language Program offers Arabic for everyone

In her “Vision Statement” for the program, senior lecturer and co-coordinator Dr. Labanieh wrote: “The Arabic program … should aspire to equip and prepare students to communicate effectively in the Arabic language and culture … to meet the demands of contemporary life and an interconnected globe.” She also calls for a student-centered approach.

With this vision, she and Dr. Masalkhi developed classes that blend Modern Standard Arabic with amiyya (spoken dialect). Arabic’s main written form is MSA, which is essential for literacy but not used in daily conversation. For students to communicate in spoken Arabic, they need frequent exposure to amiyya, Labanieh said in an interview with WMJ.

The UWM program includes six semesters of Arabic language classes, independent study, study abroad and internship opportunities. It offers a minor in Arabic.

It also meets students where they are, whether beginners or native speakers, Labanieh said. Classes and individual instruction are tailored to the needs of the students of the moment, rather than rigidly following a traditional MSA program.

Khuloud Labanieh, Ph.D., (left) assists a student during class. “The teachers really come alongside all of us,” said another student, David VandeWettering. “They genuinely want us to succeed.”

Labanieh recalled Aya, a Syrian refugee who came to Milwaukee because of the war. The native speaker with strong language skills took advanced Arabic courses but never had to attend class. Labanieh assigned her individual work, including editing projects, that challenged her and developed her language skills.

“We are seeing more heritage language learners because we are flexible in dealing with them, meeting their needs,” Labanieh explained. “They can watch or listen to recorded lectures and do their work at home.

“The university gives them retro credits for what they already know. Sometimes heritage language learners and native speakers join Arabic 5 (Arabic 301) right away. To get the Arabic minor, they need to finish three courses at the 300 level and above. Some take culture classes or go overseas for an abroad study to earn those credits.”

Masalkhi plans to develop courses in Quranic Arabic. “For Muslims, Arabic is not optional,” he said. “I presented a paper at a conference last summer and the main issue I raised was that 80% of Muslims have their connection to the Quran through mediated forms, in translations to other languages. That’s a really high percentage.”

He envisions classes that help Muslims enhance their reading and understanding of the Quran without taking them through the intense grammar and dialects taught in Arabic language classes. “It would focus on developing utility with the language so you can understand the religious aspects,” Masalkhi said.

“We pride ourselves on the breadth we can offer our students,” said Dean of the College of Science & Letters Scott Gronert, Ph.D. “Not only students, but members of the community.”

High school students take classes and earn college credit through UWM’s Early College Credit Program. Some high school students finish an Arabic minor before graduating from high school, fliers marketing the program report.

Community members can audit classes through a non-degree program. Adults 60 years old or older and people with disabilities can audit Arabic courses (and other UWM classes) for free.

Fahed Masalkhi, Ph.D., left the corporate world to pursue a career in education. “Teaching is a very human connection,” he said. “When that connection is made, it’s really more satisfying than probably anything.”

Distinguished by its quality

After the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, U.S. universities scrambled to expand Arabic course offerings to meet student demand. According to the U.S. State Department, the number of American university students enrolled in Arabic surged from 5,505 in 1998 to 35,083 in 2009 as career opportunities that required Arabic language ability grew.

UWM was way ahead of the game. “Our Arabic language instruction predates 9/11 by a decade or more,” Dean Gronert said. That’s one of the reasons UWM offers the quality it does, he added. “Quality takes time.”

Another reason is the caliber of instruction, he said. “Language instruction has, at some level, become more of a commodity. You can get it through continuing education. You can get it on your phone as an app. But the quality of people we have teaching in our Arabic program and the continued investment we’ve made for well over 30 years of being engaged in teaching Arabic distinguishes our program.”

David VandeWettering, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee junior

In his third semester in the program, VandeWettering said, “It’s definitely been challenging.” He admits he has a way to go before he can read religious texts in Arabic, but he is making progress, he said.

“The teachers really come alongside all of us,” said VandeWettering. “They genuinely want us to succeed. They’re passionate about the language and want to pass it on to other people.

“They are aware when we need to slow down or if we need individual help with certain things. They are always willing to help us figure things out,” he said.

“Honestly, the classes are tough but they are very fun,” said Naji, also in her third semester. Students work in teams on assignments and play games in Arabic. “The teachers are very understanding. They want the best for their students and are always willing to have students come in during their office hours to ask questions.

“You have to put in your time, but at the end of the day, it’s very rewarding,” she said. “I’ve definitely improved my Arabic. Now I’m actually able to read.”

In more than 30 years as an educator, Khuloud Labanieh, Ph.D., taught Arabic to more children and young adults than she can count.

Meet the professors

For more than 30 years, Sister Khuloud (Labanieh) taught Arabic to more children in Milwaukee’s Muslim community than she can count. She came to Milwaukee as a newlywed from Syria, where she earned a degree in Arabic language and literature from the University of Damascus’ esteemed Arabic Department.

In the nineties, she taught in the Islamic Society of Milwaukee’s Sunday School and Summer School. She taught at Salam School full time from 1992 to 1997, was head of its Arabic Department from 2000 to 2008 and earned its 2004 Teacher of the Year Award. She also taught Arabic courses at the Islamic Resource Center in Greenfield until those classes were discontinued.

In an interview with WMJ, Labanieh said, “I’m going to tell you a funny story about one of my students. She was in second grade at Salam School and was showing me her homework.

“She said, ‘My dad helped me with my homework.’

“I said, ‘Could you please tell him my salam?’

“She said, ‘Do you know my dad?’

“I said, ‘Yes, I know him. I taught him.’

“She went away for a few minutes and came back and asked, ‘Do you know my grandfather?’

“I told her, ‘No, no, that’s too much!’”

During busy years of teaching at Salam School and raising her three children, Labanieh earned a Master of Education degree from Cardinal Stritch University in Milwaukee. She began teaching part-time at UWM that year (2007) in addition to her full-time work at Salam School. After one overwhelming semester, she quit teaching at Salam School and continued teaching part-time at UWM.

In 2010, she decided to pursue a Ph.D. in curriculum and instruction at UWM. “It wasn’t easy because the war in Syria started in 2011. It was very difficult to work and study while coping with the news,” she explained. She suffered difficult personal losses of family and friends in Syria. Yet, she continued teaching and studying, completing her doctorate degree in 2019.

“The quality of people teaching in our Arabic program and the continued investment we’ve made for well over 30 years … distinguishes our program,” said Scott Gronert, Ph.D., dean of the College of Science & Letters.

Meanwhile, her husband Fahed Masalkhi, who had earned a master’s degree in engineering from Marquette University, worked in the corporate world, but didn’t find it fulfilling. “Corporate is a busy life that ends up serving the bottom line of the corporation. I wanted to do something that had to do with improving people’s lives. Education does.”

Since moving to Milwaukee in 1985, Masalkhi participated in a speakers’ bureau. At an event in San Francisco for The World Institute, he found himself introducing people to Islamic and Arabic culture. “This was something very useful,” he said. He also found speaking came easily to him. “There’s a flow to it. So, I thought academic training would help me develop that.”

He decided to earn a master’s degree in comparative literature. Then he began teaching classes about Arabic and Islamic culture at UWM. He continued his studies, earning a Ph.D. at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

He returned to UWM in 2015, while writing his dissertation. “When I came back, I took up the position again of teaching the cultural classes,” Masalkhi said. He also taught high-level language courses. “With the help of Khuloud, I expanded my bandwidth and learned to teach beginners, which I find more challenging,” he said.

He also created a new course called “Islam, Religion and Culture” that students can take for credit. “The culture courses are always very popular,” he said. “They have been a window of growth for our program.”

Both Labanieh and Masalkhi find teaching fulfilling. “I really, really like my students, not just as students, but as people,” Labanieh said. “What motivated me to get my Ph.D. was a desire to know how to help them more.”

“I really, really like my students, not just as students but as people,” said Khuloud Labanieh, Ph.D., “What motivated me to get my Ph.D. was a desire to know how to help [students] more.”

“It is rewarding to help heritage students learn Arabic well and develop a strong connection to their culture,” she said. “It also makes me very happy to see American students who have no background in Arabic language want to learn it because they like the language and culture.”

“I feel the same way. Students are really the jackpot here,” Masalkhi said. “Teaching is a very human connection. When that connection is made, it’s really more satisfying than probably anything.”

During busy years of teaching at Salam School in Milwaukee and raising three children, Khuloud Labanieh, Ph.D., earned a Master of Education degree and then pursued a Ph.D. in curriculum and instruction.