Originally Published By:

Picture

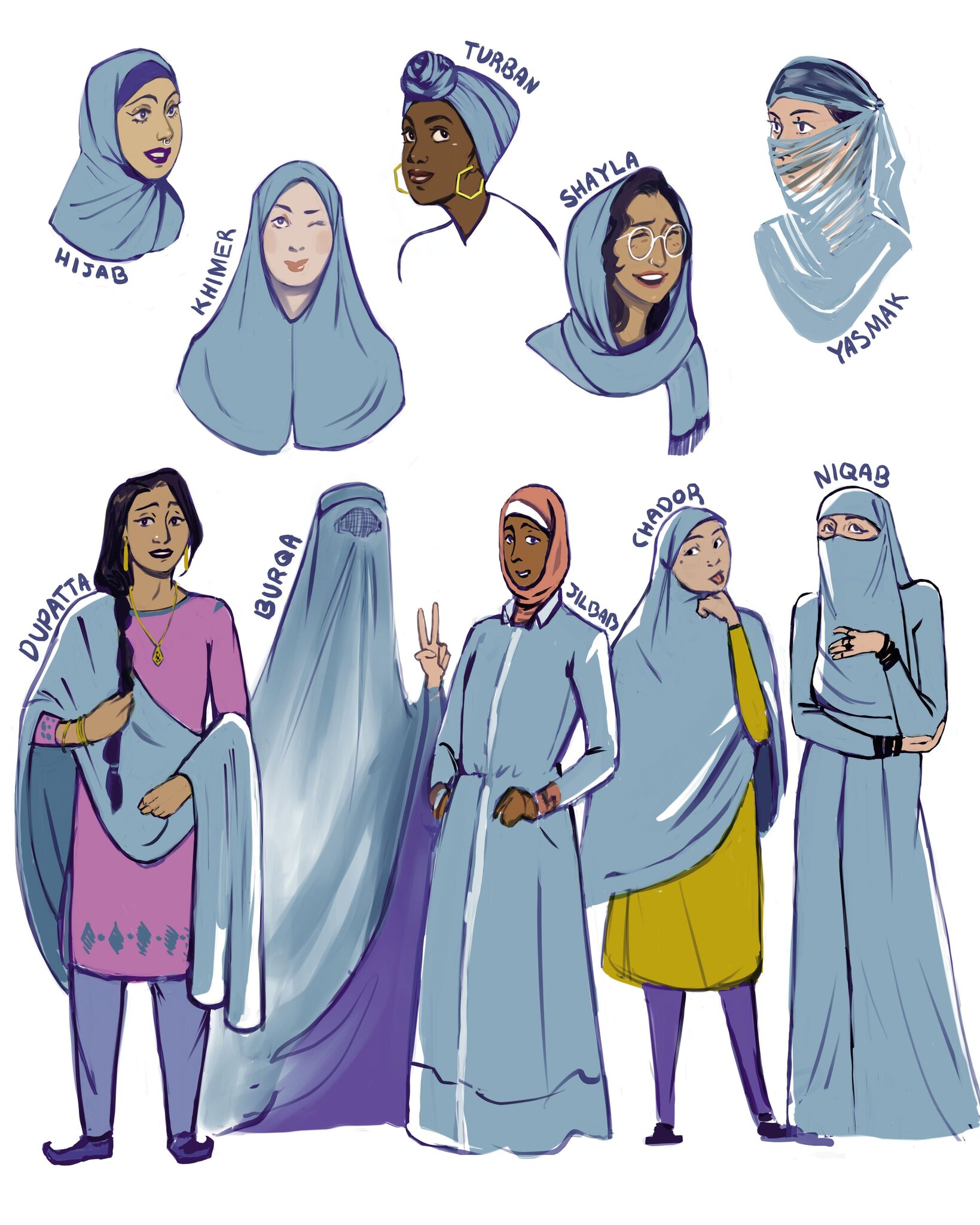

©Fahmida Azim

Tahani Amer, an astronaut who grew up in the suburbs of Cairo, endured a string of rejections before she finally secured a job with NASA’s Aeronautical Research program.

Marah Zahalka, Noor Daoud and Mona Ennab — members of the Speed Sisters, an all-female car racing team based in the Palestinian territories — defy expectations with every race they win.

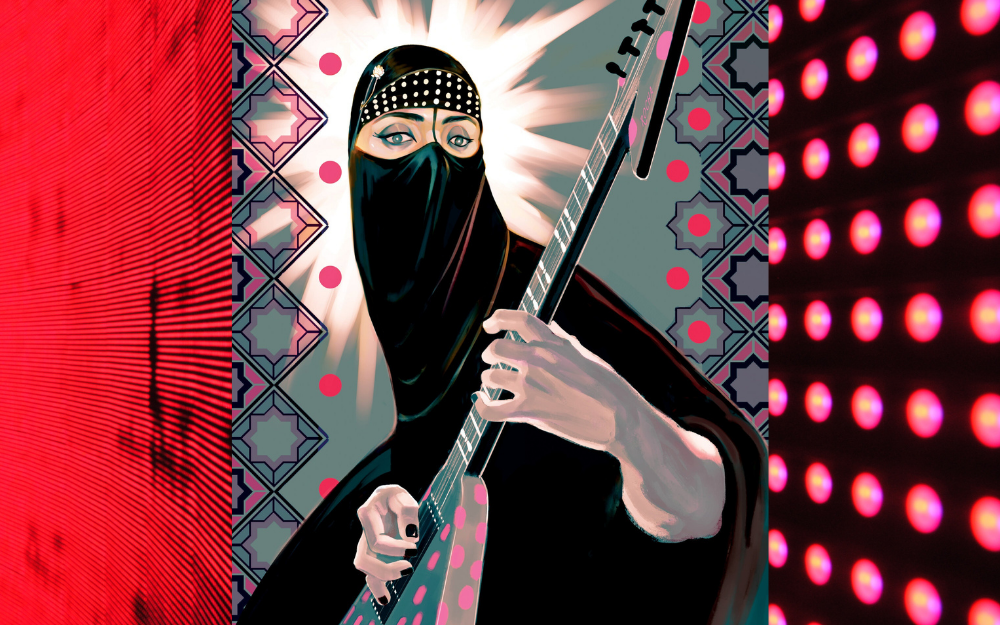

Gisele Marie Rocha is the unexpected face, in a niqab and burqa, behind Eden Seed, a thrash metal band in Brazil.

Credit… Fahmida Azim

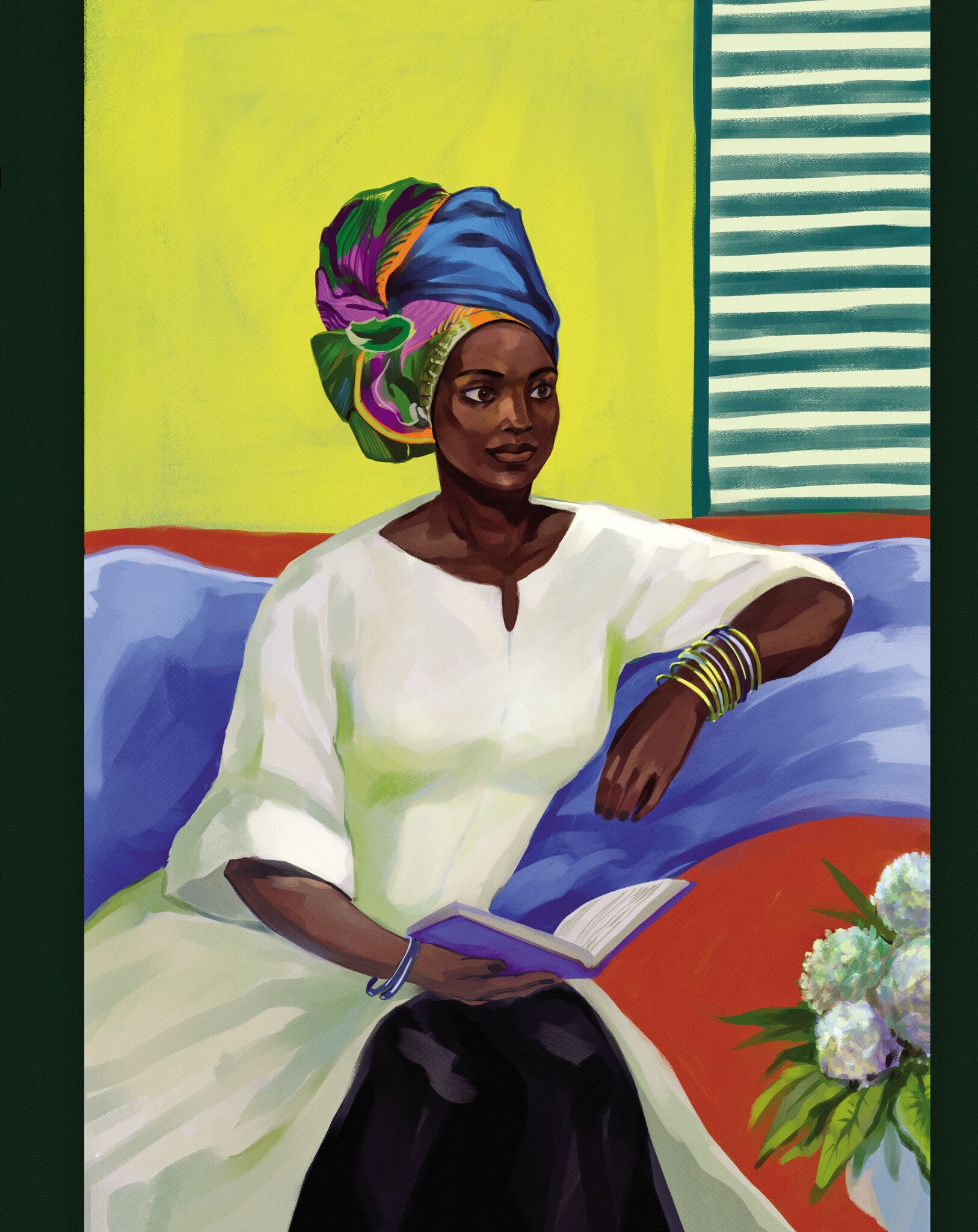

These women are validation of the premise behind Dr. Seema Yasmin’s new book — that Muslim women can be anything. The book, “Muslim Women Are Everything,” was released earlier this year.

More than 40 profiles of Muslim women — illustrated by Fahmida Azim — aim to tear down the tiresome tropes of what Muslim women are: what they look like, what they wear and what they do or don’t do. Page after page dares the reader to say these women cannot, or should not.

As for Dr. Yasmin: She is a Cambridge-trained medical doctor, a specialist in epidemiology, a journalist and the director of the Stanford Health Communication Initiative. She teaches at Stanford and is a visiting professor at U.C.L.A.

She didn’t get there easily.

She was born in Britain to a teenage mother, who was stuck in an arranged marriage. When Dr. Yasmin was just 5, her mother left the family to pursue her own education. As Dr. Yasmin tells it, “My mum was like: ‘I’m going to leave everything I know behind. I’m going to find a way to university so that you can have an education.’”

What followed for Dr. Yasmin was a childhood shuttling between worlds — the university where her mother was studying and her family’s conservative Indian Muslim community in the British Midlands.

This book was born out of a “frustration that the narratives about Muslim women were so one-sided, so narrow, so unimaginative,” she said.

Dr. Yasmin sat down with In Her Words to talk about her work and what she means when she says, “Muslim women are everything.”

Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Credit…Fahmida Azim

How did you get the idea for this book?

It all started as a very angry tweet. I was just absolutely fed up that even when Ibtihaj Muhammad, the American fencer, won a medal at the Olympics, the way that she and other Muslim women were celebrated was like, “Oh my God, look at that woman, she’s an athlete, and she’s a Muslim.”

And I was like: Wait, are you really trying to celebrate us by making it sound like we can’t do anything?

There was an editor who saw the tweet and said: This would make for a great essay — will you write an essay? And I said, no. Instead, I ended up writing this kind of prose poem. It was called “Yes, Muslim Women Do Things,” and it featured Muslim women doing amazing things like digging salad out from between their teeth and taking a nap. My point was that some of us do open-heart surgery; some of us go scuba diving; some of us are too lazy to do the dishes.

I think it really hit a nerve. A lot of people hated it. But some publishers were like, this would look great as a book.

The proposal started off about fictional women doing esoteric things and then it became about real-life Muslim women who are troubling all the definitions and messing up all the boundaries of what it means to be a woman and what it means to be Muslim.

Credit…Fahmida Azim

There’s this perverse surprise among some people that Muslim women can drive or be funny or write or, well, do anything. What explains it?

I think it’s misogyny combined with Islamophobia. When you have a dominant culture that is male and white, it allows very little space for the rest of us to be our full selves. That’s how I came up with the title. I didn’t want there to be one idea of a Muslim woman. There are some Muslim women in this book who would probably disagree with the views of some of the other Muslim women in this book. And that’s great. We need to have that disagreement.

Nevertheless, many people still have a narrow vision of what a Muslim woman is …

Right. The stereotype is a meek South Asian woman who had an arranged marriage and wears a hijab and has lots of children.

Plus, in the U.K. and the U.S., the perception of Muslim women often excludes Black women.

Credit…Fahmida Azim

How do you view your work against the backdrop of Black Lives Matter?

I don’t want to take away from the B.L.M. movement’s call for the rights of Black people, but Black Muslims do account for a fifth of all U.S. Muslims, so those struggles are certainly connected.

It was really important to me that the true breadth of the Muslim experience be included in the book. But I’ve not been shocked when people have asked me on Twitter if the book features any Black Muslim women, the expectation being that there won’t be any. The bar is so low when it comes to inclusion.

In your book, you write about the comedian Zahra Noorbakhsh and how, after one of her shows, some fans came up to her and said, “You must be one of the good Muslims.” It was so disheartening to read this.

I don’t know what Zahra said in the moment, and I’m sure that she’s had many of those moments, but I look at how she’s taken on the comedy industry, and how the industry excludes a lot of people. To me she’s been othered and marginalized, and now she’s saying she’s going to create a new model that’s way more inclusive and that brings in all voices and perspectives. I feel like that’s actually her response to that moment and to all those moments.

Credit…Fahmida Azim

You have made the point that the outside world — whether it’s male clerics or Western politicians — can’t help weighing in on Muslim women’s choice to cover. Why do you think that is?

Because they don’t believe our bodies are ours. They police our bodies. I used to wear a hijab when I was younger. I was very devout. And then at some point I decided that wasn’t going to be the way that I presented myself to the world. But that was my decision.

I think that men want to be the ones dictating how women present themselves. For some men in some countries, that might mean you must be covered. And then for others it’s like, “Oh no, we think that’s frightening,” or “That must mean you’re oppressed.” But you can be a feminist, you can have agency and you can choose to wear niqab and burqa, like Gisele Marie Rocha, a guitarist in Brazil. She has very clearly articulated why and how she chooses to cover, and how it’s a personal choice.

What hope do you have that things will change?

Things are so bad in the world right now that we have to imagine a better future. Without hope, I think I would just give up and believe that whatever narrow definition exists is all we’ve got. And I refuse to accept that.