Photos by Kamal Shkoukani

Sesame Workshop introduced new Rohingya characters and episodes in the Rohingya language with help from the Burmese Rohingya Community of Wisconsin.

As Mohamed Anwar and his three children, ages 6, 8 and 10, watched a special viewing of the new Sesame Street Rohingya episodes, he felt proud.

“It was a proud moment,” the co-founder of the nonprofit Burmese Rohingya Community of Wisconsin said about the gathering Saturday, Oct. 15, at the BRCW’s community center, 2330 W. Scott St. on Milwaukee’s south side, where hundreds of Milwaukee’s Rohingya watched Playtime with Noor & Aziz, a newly released series of videos on YouTube.

“We were with them from the beginning,” Anwar noted. Thursday in an interview with Wisconsin Muslim Journal. BRCW co-founder Andrew Trumbull also participated in the interview.

The BRCW worked with Sesame Workshop, the nonprofit educational organization that produces Sesame Street, providing feedback to help it create culturally appropriate Rohingya characters that would appeal to Rohingya children in a refugee camp in Bangladesh. In the process, the producers discovered the Noor and Aziz Muppets would be important to children of the Rohingya diaspora as well.

Watch Playtime with Noor & Aziz here

Sesame Workshop sought help from Milwaukee’s Rohingya people

Before Sesame Workshop contacted Anwar and Trumbull in 2019, Anwar had never heard of Sesame Street, perhaps the longest-running TV show for children. It first aired on PBS in 1969.

“All Rohingya parents are at a loss,” Anwar explained. “We didn’t have education. We played with rocks, sticks and sand. I didn’t have TV or internet until I came to America. I had never seen Sesame Street. Most Rohingya children in refugee camps have never seen television.”

Rohingya are a Muslim ethnic minority in Myanmar, a Buddhist-majority country, who have been oppressed for decades. In what the United States declared a genocide, Myanmar’s military junta unleashed a wave of violence in 2017 against the Rohingya, who fled in large numbers to surrounding countries. Some eventually resettled in other countries, including the U.S. Anwar estimates there are about 3,000 Rohingya living in Milwaukee.

Sesame Street uses puppets and comedy sketches to bridge cultural and educational gaps. In 2018, its producers set their sights on Rohingya children in Cox’s Bazar in Bangladesh, the world’s largest refugee camp.

Members of the Sesame Workshop pose with Sesame’s new Rohingya Muppets Aziz and Noor.

“If we can help these children get off on the right start, where they can thrive, then they have so much more of a chance of succeeding later on,” Sherrie Westin, president of social impact for Sesame Workshop, said to reporters in a 2020 NBC news story.

Sesame began research in the refugee camp to produce videos about fictional 6-year-old twins who live in Cox’s Bazar. They sought feedback from families in the camps about their characters, Noor and Aziz.

In 2020, volunteers from the Burmese Rohingya Community of Wisconsin visited more than 20 Rohingya families in Milwaukee, showing sample Rohingya Sesame episodes and sent feedback to Sesame Workshop.

The pandemic halted that work in 2020 and the producers turned to Milwaukee’s Rohingya community, where the largest Rohingya refugee population in the United States lives.

When Sesame Workshop reached out to the BRCW, “I was super thrilled,” said Trumbull. “Growing up in America, I obviously knew Sesame Street. I told Anwar we definitely have to work with them.”

In 2020, Anwar and Trumbell visited more than 20 families (37 adults and 47 children), house by house, to share sample videos of episodes with new Rohingya Muppets. They collected feedback from the Rohingya families, which they sent to Sesame.

“The one thing I heard repeatedly is that we can see cartoons with many images but no Rohingya,” Anwar said. “They were so happy to see Sesame created something new–Rohingya Muppets.”

Meeting Noor and Aziz

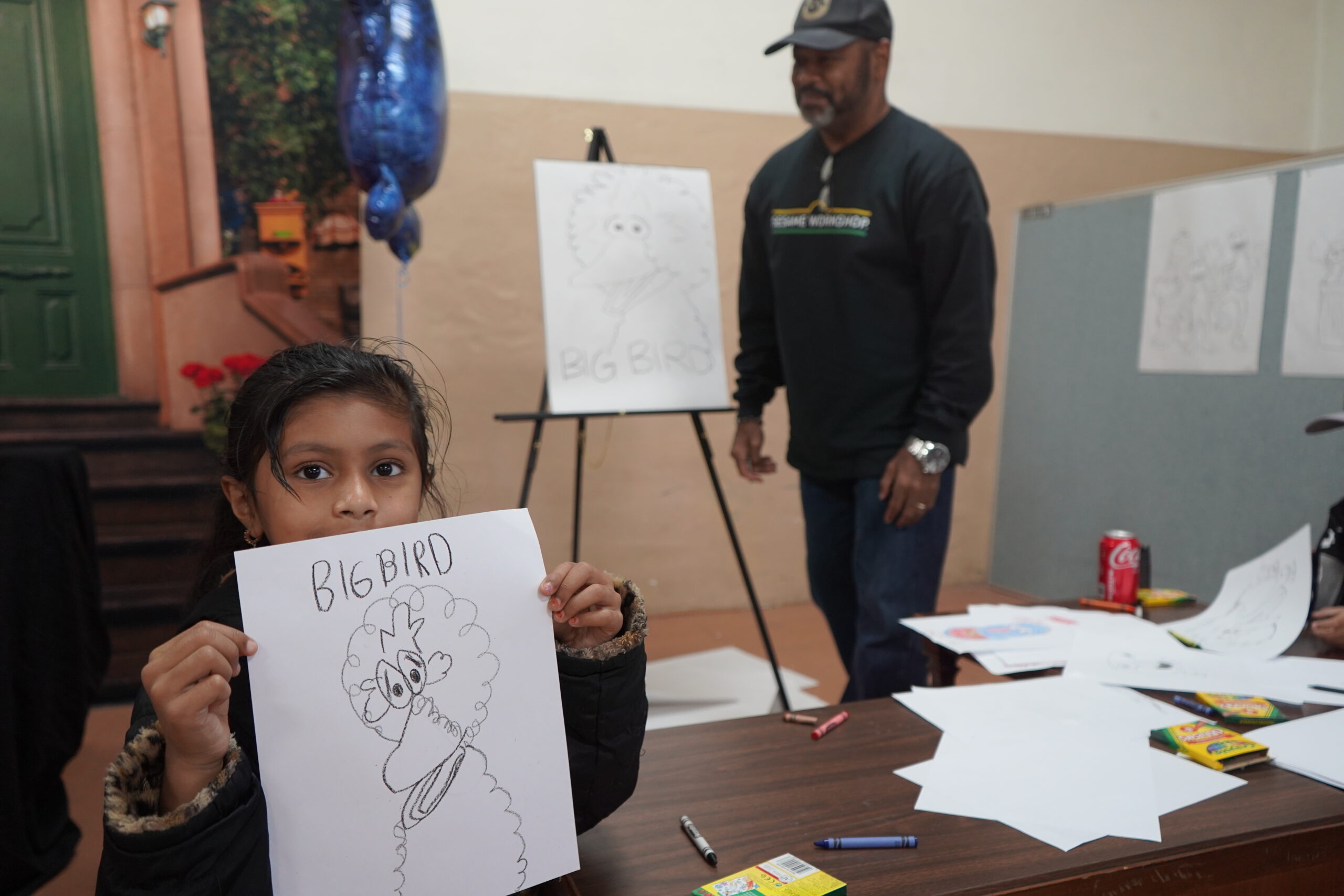

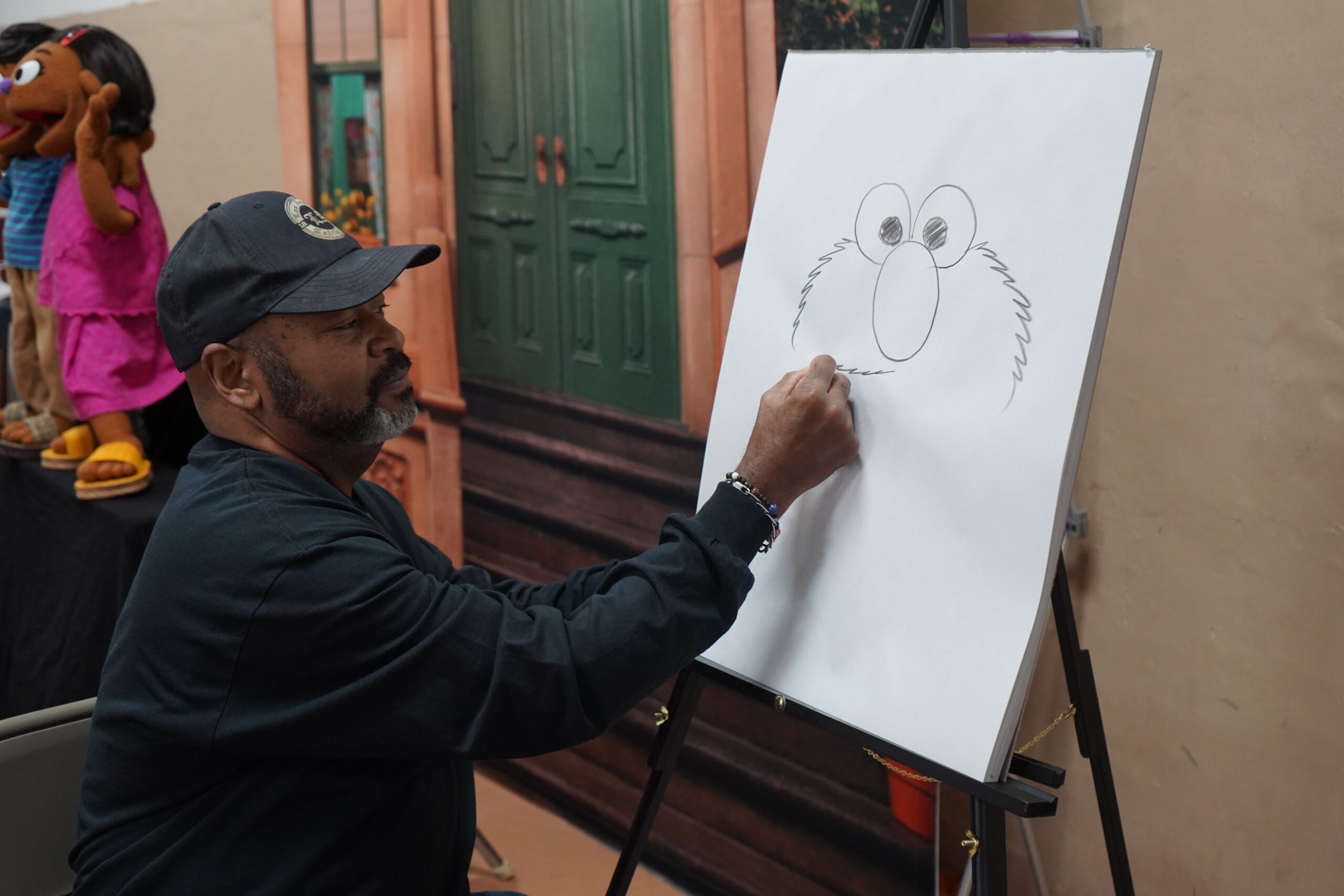

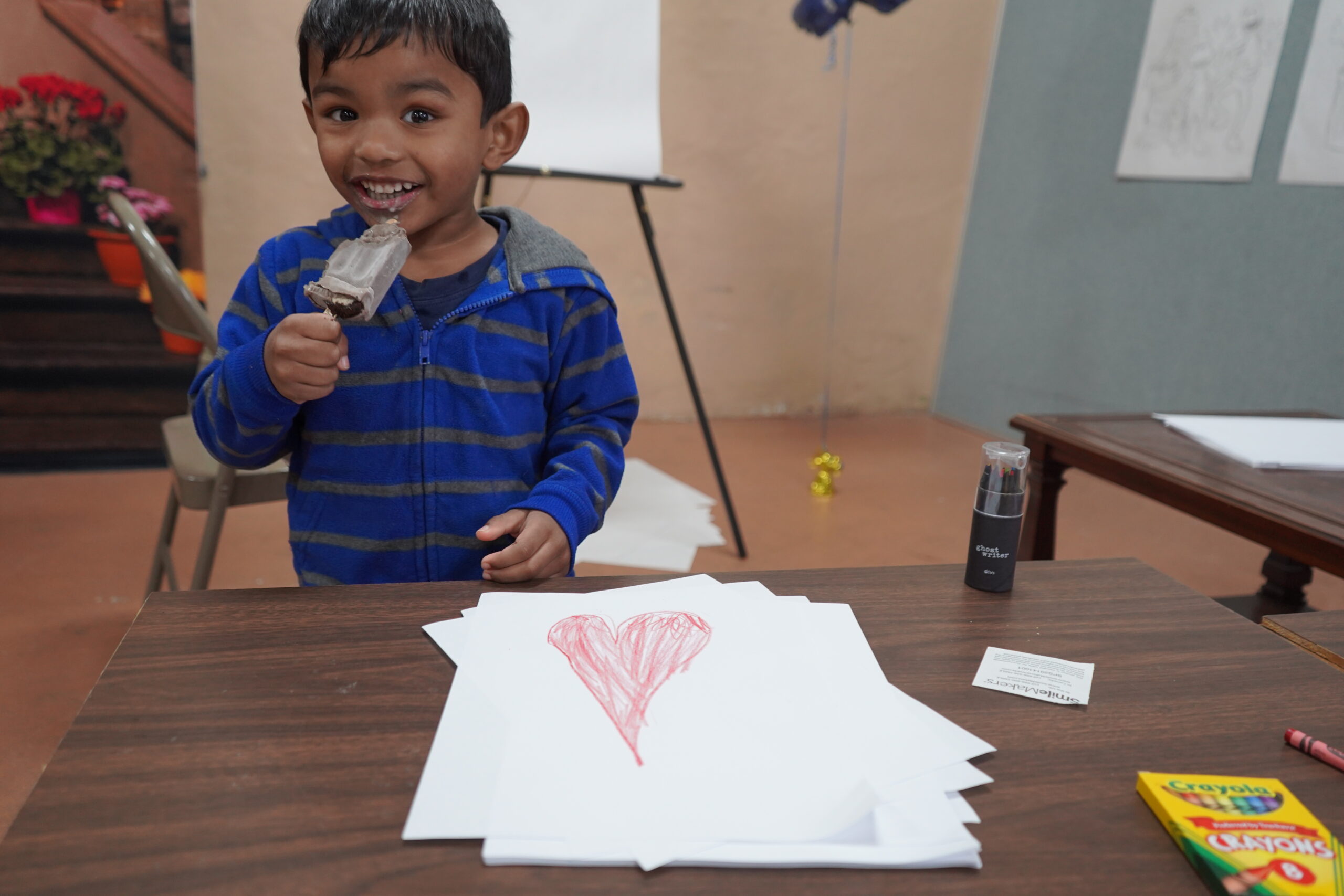

Hundreds attended the special viewing Oct. 15 of the Rohingya Sesame Street episodes at a family event held at the Burmese Rohingya Community of Wisconsin Center. In addition to the screening of new Rohingya Sesame Street episodes, the event included lunch, games and art activities for children, vaccination and voter registration drives, information tables and gifts.

Twenty-six sponsors helped make the event a success, Anwar said. They included: Islamic Society of Milwaukee, Hanan Refugee Relief Group, Milwaukee Muslim Women’s Coalition, ICNA Relief Chicago, Books Unbound, International Literacy and Development (ILAD) Rohingya Program, Our Peaceful Home, AAPI Coalition of Wisconsin, Hayat Pharmacy, Milwaukee Public Schools, Lynden Sculpture Garden, League of Women Voters-Milwaukee County, Asian Americans Advancing Justice, Catholic Charities of the Archdiocese of Milwaukee and SEA Literacy.

“Parents had been asking when the videos were coming,” Anwar said. The event drew a big crowd of Rohingya families.

Five hundred food boxes were distributed (and another 100 people arrived too late to get one); 175 vaccinations for COVID and flu were given; 200 popsicles eaten; and many children received jackets and gloves for the winter, Anwar reported.

The highlight of the event was the screening of videos that featured Rohingya characters speaking the Rohingya language, Trumbull and Anwar agreed.

“What Sesame Workshop dis was really pioneering work,” Trumbull said. “There is not much available for the Rohingya in their language. And because it is only a spoken language–it has no script–the work is difficult.

“Sesame Workshop made 26 episodes and they are planning to do over 100,” he added.

Rohingya Sesame–A bridge between two worlds

“That the new episodes use the Rohingya language with English is most exciting,” Trumbull said. “The issue Rohingya in the diaspora face is that the parents don’t speak English well and they are worried their kids are not learning the Rohingya language.”

The language, as well as the episodes set in the refugee camp in Bangladesh, provide a path for Rohingya children in the diaspora to connect with their heritage, Anwar said.

“Rohingya kids are smart and here they have all these tools and opportunities, and the internet,” he said. “But even when we explain to them (Rohingya children born in America), it is hard for them to understand how our lives were and the difficulties we went through.”

These videos, as well as documentaries such as “Wandering: A Rohingya Story,” which was featured at the Milwaukee Muslim International Film Festival, “help them connect the dots,” he said. In that documentary, “they see children in the refugee camp playing in the rain with no shoes. For our kids growing up here, this is something very important for them to understand.”

The Sesame series may also play an important role in preserving the Rohingya language, Anwar said. “We Rohingya parents have a conflict with time. We have only one or two hours a day with our children. They go to school and then after-school programs. One or two hours is not enough for them to learn the Rohingya language.

“I talk to my kids in Rohingya and they respond in English. It is very important for the Rohingya diaspora to give kids their language.”

The Sesame Rohingya episodes provide additional exposure to the language and that’s important, Trumbull agreed.