In North American media, Muslims are primarily visible as deliverers of trauma through acts of terrorism. But many of the 70 million refugees worldwide who have flooded camps in Turkey, Jordan, and Bangladesh fleeing violence in Syria, Yemen, Iraq, and Burma are Muslims who are the victims of trauma and even attempted genocide.

Cities like Milwaukee are engulfed in their own trauma crisis, with gun violence impacting families for generations. Milwaukee is also beginning to confront the ways violence and displacement impact its immigrant and refugee communities.

Deborah A. Davis, a therapist who works withUWM’s Trauma Studies Association invited noted trauma specialist, Omar Reda, a Portland, Oregon psychiatrist,to hold a series of 10 workshops and talks in Milwaukee. Aurora Behavioral Health provided additional funding. The Milwaukee Muslim Women’s Coalition hosted two well-attended events at the Islamic Resource Center led by Dr. Reda.

Reda is the author of several books on healing refugee trauma from a culturally specific Islamic perspective, including On the Shoulders of the Prophet, the first volume in his Family Bonding series, and Untangled: A Go-To Guide for Caregivers of Traumatized Children, Families, and Communities.

The trauma and chaos caused by the overthrow of Libyan strongman Muammar Gaddafi as part of the Arab Spring revolution placed a permanent mark on Dr. Reda’s life. His grown nephew, a young father, was murdered by ISIS. And Reda himself had been forced to escape in 1999 when Gaddafi tried to have him arrested. He became an asylum seeker in England, where “the judge decided that I don’t meet the criteria because there is no evidence of torture on [my] body. So I said there is torture on my mind that you cannot see.”

Trauma, says Reda is “the invisible elephant in the room” in the Muslim community.

Dr. Reda works with the Muslim community in Portland at its mosques and community centers and has founded a series of programs and workshops to promote community psychosocial health and heal trauma. He also travels frequently to work with victims of trauma. Cox’s Bazar, where Dr. Reda conducts workshops for Rohingya refugees, is no longer a “refugee camp” but a settlement on the Bangladeshi coast, home to 900,000 refugees.

Dr. Reda calls his work Untangled because many families are tangled in a trauma story without even realizing it. “If there is a trauma story, they keep it a secret,” Dr. Reda said.“While parents are chasing the American dream, children go to bed with full stomachs and empty hearts.”

Reda’s approach aims to strengthen families and give young people hope by helping them to connect with each other. As we often hear, Islam is not about the individual, it is about connecting the individual to the community.“Our prophet was the best counselor,” Dr. Reda believes. “He sat down with people. He was especially attentive to children. If you are a harsh person, people will not come to you. The young companions felt safe around Muhammad (PBUH). They climbed on his shoulders.”

At the Wednesday afternoon session at the Islamic Resource Center, one woman concluded that, within the community, “the sisters are in good shape. But if you look around, you see only 3 men in the room” for a workshop on mental health and Islam.

Reda responded that “by the time men call me, the issue is usually very advanced. Things are quite complicated. It’s better if you ‘untangle’ early.” He recommends groups like the one he founded, the Sons of Adam youth group. His wife began a similar group for the Daughters of Eve. “Activities are helpful for engaging men,” Reda said, who views what the groups do as “coaching boys into men.”

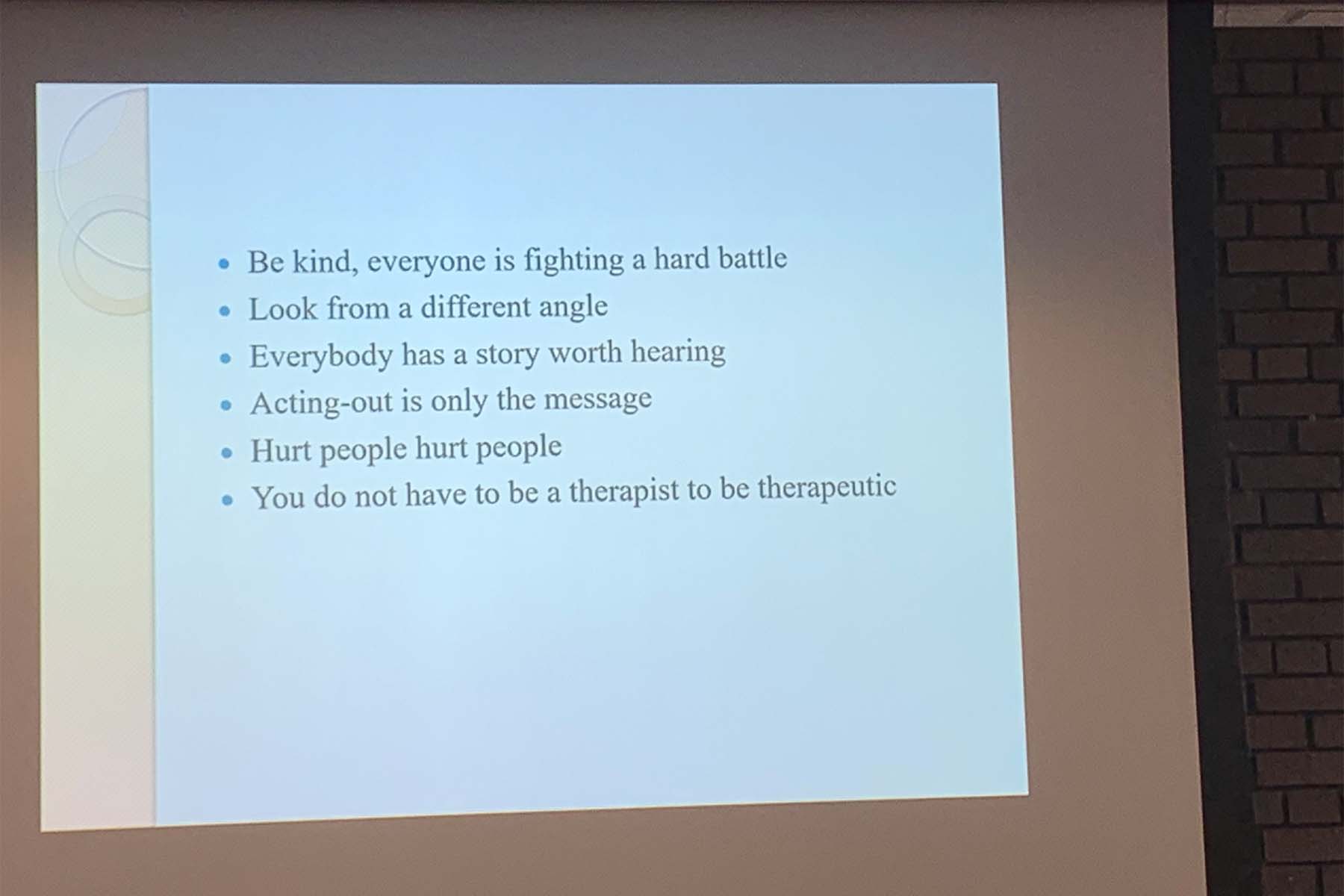

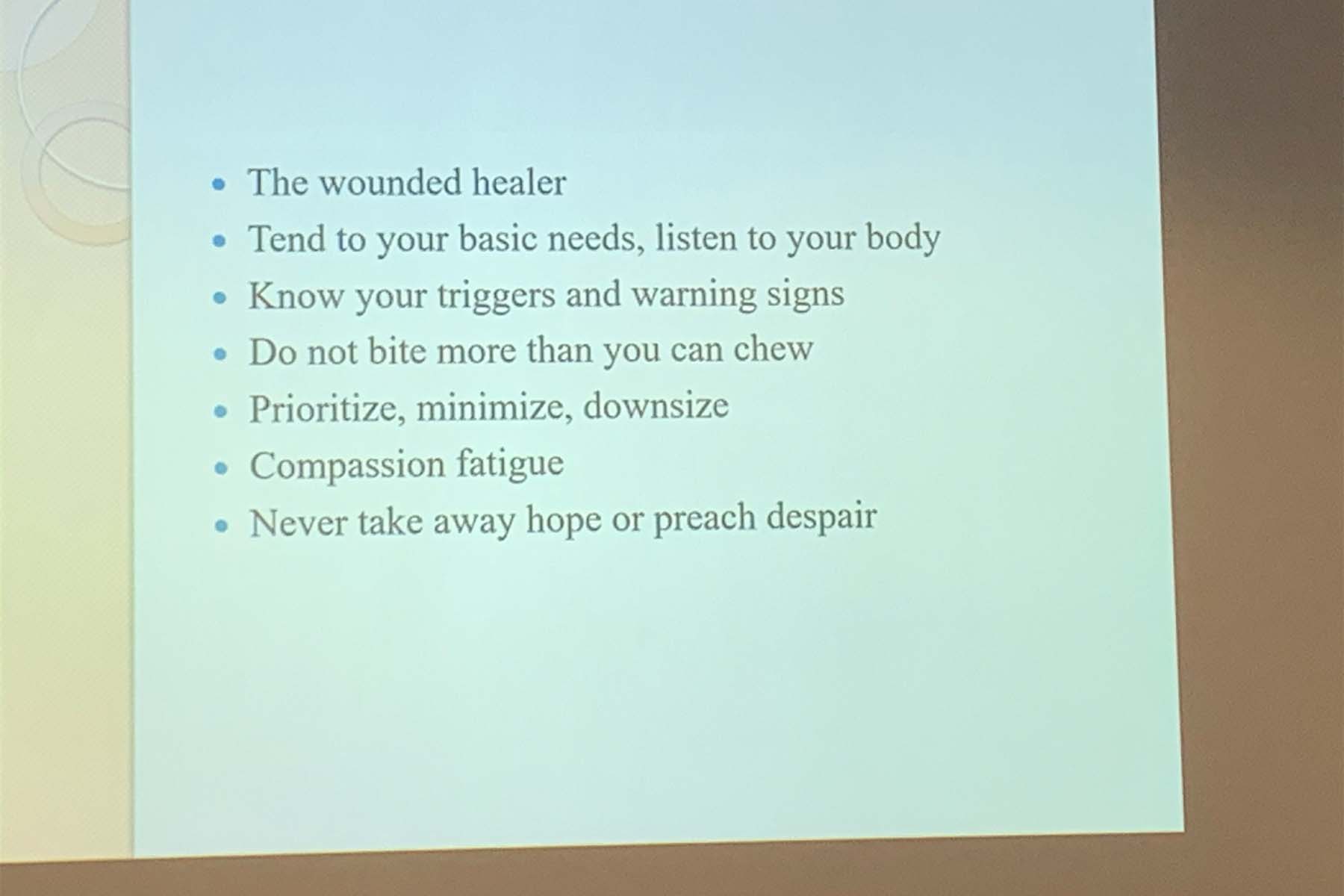

“Most people are resilient,” Dr. Reda said. “They can recover with just community support.” Of course it helps that “Muslims are very close-knit, they stick together and have respect for elders.” But if more help is needed, the next level, he said, may be the “non-mental health clinical professionals,” for example yoga classes and meditation groups. “If you have limited resources, build community capacity. For support, you just need to be supportive and genuine.”

The good news, he said, is “I see more involvement on the part of men, including Syrian refugees.” However, “If we just invite them to our space, they will not come. So we go to them. We have a mobile access team. We go to their homes, and we invite them to a retreat at our camp or to a talk at the masjid. In Portland, the imams are open-minded and receptive,” Reda said.

Dr. Reda said that in Portland, “when I reached out to the imams, they said, ‘Where have you been? Because we are exhausted.’”

This surprised many in the audience.When founding the Milwaukee’s first Muslim culturally-specific domestic violence program Our Peaceful Home, Janan Najeeb said she found “only the younger imams” were interested in participating.

Reda suggested that older imams “may feel that their mediation, although not trained, is more effective [so] we approached them in a very calculated way. We talked to the imams about self-care. They are trying to hold the community together like glue.”And they needed support for themselves.

This seemed to strike many attendees as a valid approach. “We need to support leadership development skills for our imams,” one woman said. Another idea inspired by Dr. Reda that afternoon was that, as one participant said, “Women and youth have to be on the boards of our mosques. Give voice to new blood. Our kids have the [Muslim] identity, but they need to be active and they need to be involved.”

Portland has many workshops and programs for Muslims, both at mental health centers and community centers and at local masjids. The city even has a Yelp Page that lists the 10 Best Mosques.And while Milwaukee doesn’t have Dr. Reda, he complimented the city, saying it is “as progressive as Portland” because “you have such a welcoming space” like the Islamic Resource Center.