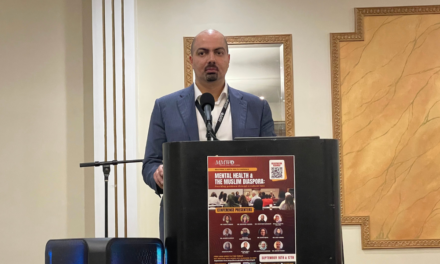

Photos by Sandra Whitehead

Medical College of Wisconsin Professor Aasim I. Padela, M.D., founder and president of the Initiative on Islam and Medicine, discussed Islamic bioethics during a January workshop on end-of-life decisions at the Islamic Society of Milwaukee.

The Islamic Bioethics & End-of-Life Healthcare Decisions workshop had just begun when one of the speakers received a WhatsApp message. Aasim I. Padela, M.D., Professor of Emergency Medicine and Medical Humanities at the Medical College of Wisconsin, and the founder and president of the Initiative on Islam and Medicine, stepped up to the podium.

“While I was sitting here, I got this on my phone. ‘My brother has been dealing with AML (acute myeloid leukemia), which is an aggressive cancer type, for the last two years,’” he read. “’He’s a medical student and most of us in the family are physicians. We were discussing end-of-life decisions. As a medical family, we are very well versed with the medical aspects. Basically, AML has a 33% five-year survival rate. We are having a hard time with trying to understand the Islamic side. He is intubating in the ICU. What should we do?’

“I often get texts like this,” Dr. Padela said. “Obviously, they want an Islamic response. Should they keep him on intubation or should they withdraw life support?”

Dr. Padela asked the audience, “Imagine your child is facing an aggressive cancer … a young person with aspirations to be a doctor. What do you do? What does Islam have to say?”

About 50 people attended the four-hour workshop, Islamic Bioethics & End-of-Life Healthcare Decisions, held Jan. 31 at the Islamic Society of Milwaukee. It featured experts with backgrounds in medicine, palliative care, hospice and Islam. Speakers made presentations and led discussions about practical steps, resources and strategies to help Muslims “transition from a state of uncertainty about end-of-life healthcare to thoughtful preparation for it,” said the workbook given to participants.

The workbook, Islamic Bioethical Considerations for End-of-Life Healthcare: A Guide for Muslim Americans Navigating End-of-Life Decisions with Islamic Values and U.S. Healthcare Tools, aims to support Muslim Americans as they navigate end-of-life healthcare in a way that honors both Islamic ethics and U.S. laws, it states. Its publication was sponsored by the Initiative on Islam and Medicine, Muslim Community & Health Center and the Medical College of Wisconsin. For more information about the workshop and workbook, email contact@medicineandislam.org.

At the workshop, Dr. Padela, an Islamic bioethics expert and clinical researcher, addressed Islamic bioethics in end-of-life decisions. Renee Foutz, M.D., a hospice educator and clinician, explained what hospice is and isn’t, clarifying misconceptions and answering questions from the audience.

A case study review concluded the workshop. A panel of three medical professionals, Padela and Foutz, and Ismail Quryshi, M.D., from Froedtert and MCW, who practices hospice and palliative care and internal medicine, used the case study “to bring all the workshop topics from theory to practice,” team member and community academic researcher Laila Azam, Ph.D., M.B.A., told the Wisconsin Muslim Journal.

This article focuses on Dr. Padela’s discussion of Islamic bioethics in end-of-life decisions.

Aasim I. Padela, M.D., is a professor of Emergency Medicine and Medical Humanities at the Medical College of Wisconsin.

Developing education about Islam and end-of-life decisions

Both the workshop and workbook drew on more than a decade of research, community engagement and Islamic ethical scholarship. Over the past four years, a multidisciplinary team of academics and community leaders in southeastern Wisconsin advanced the research and developed educational materials. The team included representatives from MCW, MCHC, and local and national hospice and palliative care programs.

Dr. Padela explained: “We brought together experts from different domains, from chaplains to hospice directors, to people like myself from Islamic Medicine and members of the Muslim community to create this workshop and other materials, like the booklet.”

The goal has been to give Muslim Americans the knowledge and context of end-of-life decisions they will face, as well as resources and guidance to prepare for those decisions, and engage in planning with their families.

Applying Islamic ethics to end-of-life decisions

Dr. Padela’s “entire career has been devoted to exploring both sides of Islamic biomedicine,” he said. “I spent time studying at Al Azhar University in Cairo (the chief center of Islamic learning in the world). I have a degree in Arabic. I just spent some time abroad, studying sharia in Arabic. I also spent some time as a fellow at the Oxford Center for Islamic Studies, researching issues related to Islamic moral theology, and I continue to spend time with scholars from our tradition, studying various topics privately or in classes to try to get a handle on how we mine our tradition to address issues at the intersection of Islam and biomedicine.”

Dr. Padela also has a B.A. in Classical Arabic & Literature and a B.S. in Biomedical Engineering, both from the University of Rochester, an M.D. from Weill Cornell Medical College, an M.S. degree in Health & Health Care Research from the University of Michigan and experience in multiple fellowships and research positions.

“A lot of us want to hear an expert explain what Islam has to say,” he said. “This is not that kind of talk. Our tradition has many different ways of thinking about what is right and good.”

And medicine is not just the healthcare system, he explained. There’s a philosophy and theology to medicine. There is sociology and economics, financial drivers and healthcare policies. “There’s an entire social science perspective about what’s occurring. You also have to look through social, scientific, biomedical and philosophical lenses. The Fiqh Council of North America, for example, brings experts together from different domains so they can understand the problem correctly and offer new U.S. guidance … about how to prepare for and think about death.”

“Islam encourages planning for all stages of life—including our return to Allah,” the workbook says. The workshop and the guide are starting points for individuals to explore Islam and their own wishes about death and dying. They “support approaching the end-of-life with peace, understanding and trust in Allah’s mercy.”

“That’s the rollercoaster ride you’ve signed up for,” Dr. Padela warned the audience. He urged the workshop participants to begin their own journeys of exploration at the crossroads of Islam, medicine, life and death.

About 50 people attended a community education workshop Jan. 31 on Islamic bioethics and end-of-life healthcare decisions.

Preparing for death in America

When we think about a “good death,” we picture ourselves at home, surrounded by comfort from a loving family. “But here in the United States today and in many industrialized countries, what we have is ‘medicalized death.’ The fact is that the majority of people here die in a hospital, surrounded by sterile environments and beeps and bongs of machines, sometimes sedated.”

While people desire to be at home, oftentimes they’re not prepared to think of how to get there, he said. The system is set up in a way that makes it easy to end up in a hospital. It requires work on our end to die at home.

“And 80% of deaths in the United States occur where there is some conversation about withdrawing or withholding life support. Do you want to have CPR? Do you want to be DNR (do not resuscitate)? Most Muslims ask religiously, ‘What can we or can we not do?’

“A lot of healthcare resources are spent in the last moments of life,” he observed. “There’s a larger myth in our society that more is better, that new is better. Neither is necessarily the case. More interventions don’t necessarily lead to better health outcomes. New technology doesn’t necessarily mean better. That myth drives people to the healthcare system.

“We can’t just ask ourselves these questions at the last moment,” Dr. Padela said. “That’s why we are having this workshop … I would argue that what we need is to consider what dying well looks like in our tradition and for ourselves, then fit our decisions in that.”

Renee Foutz , M.D., is an assistant professor of Medicine and Emergency Medicine at the Medical College of Wisconsin.

Let’s talk about death

The team surveyed 150 Muslim Americans in Chicago, asking if they had talked with their doctor or loved ones about their end-of-life care decisions. They found the majority of individuals had not even thought about talking with someone else. “They said they were not even ready to talk,” Dr. Padela noted. “Why are we passive participants in one of the most important aspects of our life, our death?”

One problem is knowledge gaps about medicine—what is palliative care? What is hospice? What exactly does a “Do Not Resuscitate” order mean? Are these things Islamically approved? How does medicine define death? What is death in Islam?

Another problem is that we don’t talk about the end of life with our families and in our communities. “We should today unburden our future selves and our loved ones by investing in these conversations, seeking knowledge and understanding,” Dr. Padela said.

Exploring end-of-life decisions will give us much more than preparedness for that time in our lives or in the lives of our loved ones, Dr. Padela explained. “That’s because to understand the end of life, we have to have a complete picture of what our journey is. One must put everything in context, not just the questions and decisions.”

As the workbook concludes: “For Muslims, caring for a loved one who is nearing death is not just a medical or logistical obligation; it is a deeply spiritual act with plentiful opportunities for service and patience that carries tremendous reward.

“Providing comfort, maintaining dignity and surrounding a loved one with care and remembrance of Allah can turn a difficult experience into a profound and transformative moment, for both the patient and those who care for them.”