Photo by Cherrie Hanson

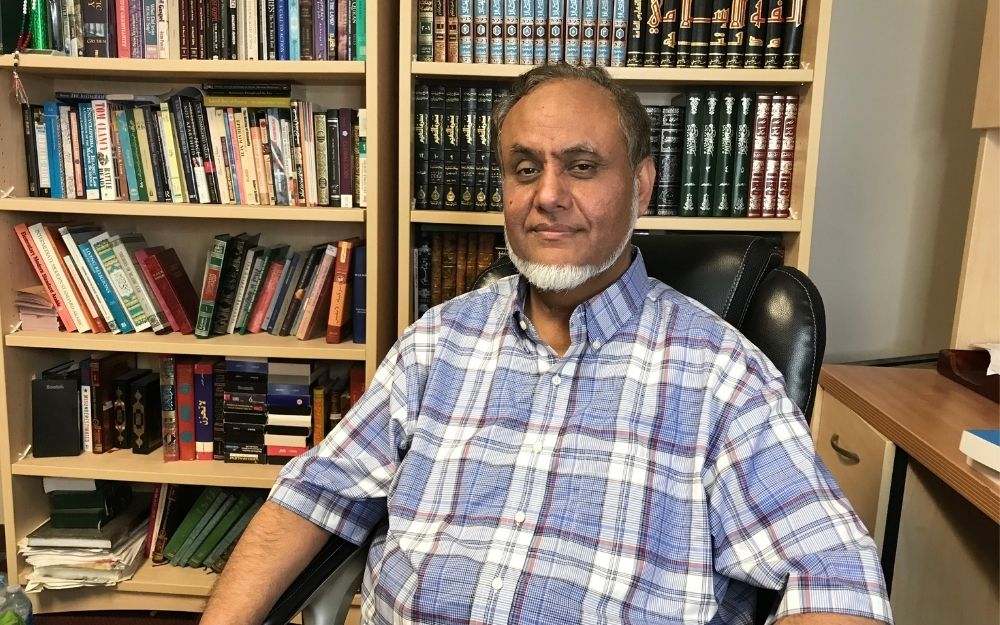

Zulfiqar Ali Shah, Islamic Society of Milwaukee religious director since 2006, is a renowned Islamic scholar who hopes to inspire critical thinking among Muslim youth.

Wisconsin’s prolific, erudite religious scholar Zulfiqar Ali Shah, Ph.D., 59, was once a teenager full of questions about his family’s Muslim faith. Why did all the scientists in his premedical textbooks have Western names? Why were Western countries advancing technologically and economically while Muslim countries seemed stuck in the past? What has Islam offered the world? Should I continue to be a Muslim?

A fan of Western movies as a young man, Shah developed a fascination with the Western world. As a university student, he even sought the counsel of a Christian cleric and studied the Bible.

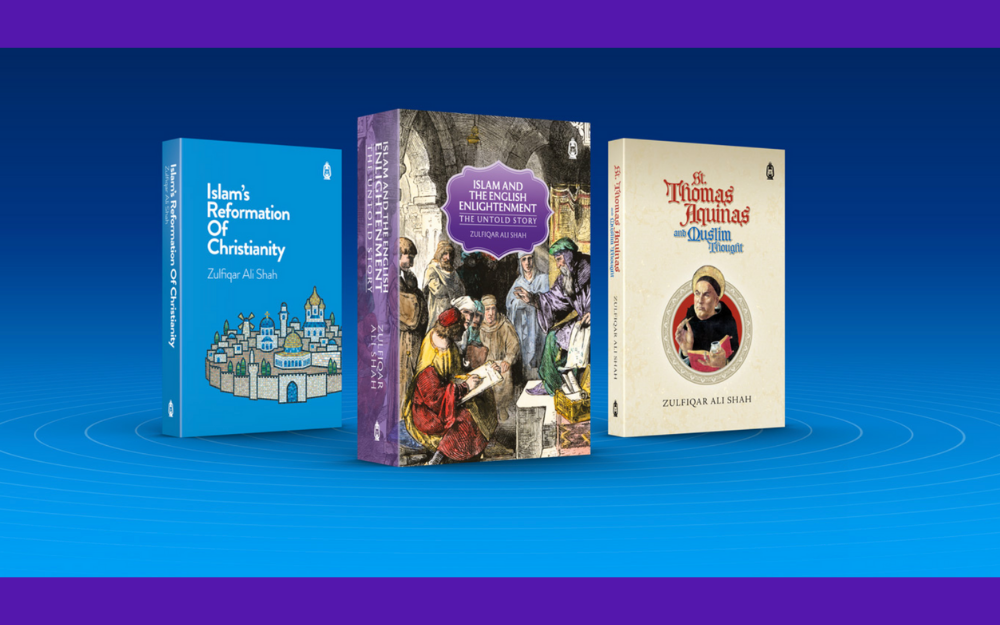

Today Dr. Shah is a leading influence on Islamic thought in the West. He just completed three hefty books—a total of 1,368 pages, weighing 4.4 lbs—each about specific aspects of Islam’s impact on Western thought. Islam’s Reformation of Christianity, St. Thomas Aquinas and Muslim Thought, and Islam and the English Enlightenment: The Untold Story were all published in May by Claritas Books in the United Kingdom. All three received accolades from major theologians and religious scholars across the globe, and all are featured in the May/June 2022 issue of Islamic Horizons, the Islamic Society of North America’s national magazine.

In his office, tucked behind the large prayer area on the main floor of the Islamic Society of Milwaukee, where he serves as religious director, Shah shared the story of how, once a rebellious teenager, he passed through a crisis of faith and a near-death experience to become a devoted Islamic scholar and cleric.

Dr. Shah’s scholarship to be featured Saturday in online seminar

Islamic Institute of Development & Research, a U.K.-based global Islamic educational organization, in collaboration with Claritas Books, will host a seminar tomorrow featuring Shah’s book Islam and The English Enlightenment: The Untold Story.

The three-hour conversation with Dr. Shah on his “pioneering work” begins at 7 a.m. CDT, tomorrow, Saturday, June 25. If you register, you will also have access to a recording.

See more information and register here.

Shah’s leadership in Milwaukee and beyond

At Greater Milwaukee’s Muslim events big and small—from jumaa prayers and Eid celebrations to funerals to conferences—Dr. Zulfiqar Ali Shah is often present, though not always front and center. Like a coach, he guides his community from the sidelines, consulting the shura and young imams. He also regularly participates in gatherings fostering interfaith understanding or protesting injustice, where he more often takes center stage.

He dresses like the late children’s TV host Mister Rogers, in cotton shirts and khaki pants, with a cardigan sweater if there’s a nip of coolness in the air. Like Rogers, Shah speaks quietly. Many find his calm, confident tone comforting.

Shah sometimes asks listeners what language they prefer. He is fluent in English, Arabic, Urdu, Hindi and Punjabi, and has “working knowledge” of Persian and Pashto.

As ISM’s religious director, Shah guides Greater Milwaukee’s Muslim community as it strives to follow Islam and understand the Qur’an, along with the hadith and sunna, the teachings of the prophet and the precedent established by the prophet’s way of life, respectively. But his influence extends well beyond Milwaukee and even Wisconsin.

Shah serves as executive director and secretary general of the Fiqh Council of North America, the highest Muslim juris body on the continent. Its 22 Islamic scholars from the United States and Canada answer questions and develop policy papers regarding Islamic law (shari’ah) in the North American context. Government bodies, including legislatures and courts, Muslim organizations, healthcare organizations and the general public consult the Fiqh Council when they have questions about the application of shari’ah to topics like medical ethics, Islamic finance and inheritance, interfaith marriage and more.

And then there’s his research. Shah frequently addresses a wide range of legal and theological issues in books, research papers and presentations around the world. He tackled the question of whether Muslims today must sight the moon to begin and end Ramadan in a 2009 book. He explains that certainty, not actual sighting, is the real objective of shari’ah and the Qur’an does not mandate physical sighting. Shah spoke in 2018 on ethical issues around organ donation at the University of Chicago’s Initiative on Islam and Medicine’s Conference on Islam and Biomedicine. Today he is exploring the question of the transplantation of pigs’ hearts into humans and whether Muslims can eat lab-grown meat.

Eight of his books are published, “so far,” he adds. One is translated into 31 languages.

His 2012 book, Anthropomorphic Depictions of God: The Concept of God in Judaic, Christian & Islamic Traditions, Representing the Unrepresentable, is a monumental study that grew out of Shah’s doctoral studies in comparative theology. “A powerful case is made that belief in the unity and transcendence of God is better safeguarded in the Quranic tradition than in earlier scriptures … presented in the Hebrew Bible and in traditional understandings of Christology,” writes Shah’s mentor and doctoral thesis supervisor Rev. Paul Badham, Ph.D., University of Wales professor of theology and religious studies. “The great virtue of this book is that it is fair to each of the traditions that it covers.” It is “a challenging book which Jewish, Christian and Islamic scholars will all benefit from reading.”

Shah’s three recently published books together offer an in-depth look at Islam’s impact on the West over the past millennium and more, and he’s not done. “I’m writing a series,” he explained. “The fourth and fifth books will come out by the end of next year.”

The first focuses on the 7th, 8th and 9th centuries, “the original Islamic centuries,” Shah said. The second discusses medieval interactions between Christian intellectuals and Muslim thought. The third covers the 17th and 18th centuries, exploring the influence of Islamic sciences and thought on the thinkers of the English Enlightenment.

Shah’s fourth book in the series will be about Islam and the French Enlightenment and French Revolution, he said. And the fifth will talk about Islam and founding fathers of America.

Back to our story – Part 1: A crisis of faith

President Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq welcomed international youth leaders to the palace in 1986. (Left) President Zia greets Zulfiqar Ali Shah. (Right) Shah and fellow student in palace hallway.

Born into a conservative Muslim family in Pakistan, Shah’s father, a well-known teacher and scholar, pushed Shah to memorize the Qur’an at a young age, “without incidentally understanding a word of it,” Shah noted. He admired his father, who was also a political leader—a councilman and then mayor of his village and an activist. “He is my model,” Shah said.

Yet, “it increasingly seemed to me that the words Allah, Qur’an and Muhammad were an impediment to my fun.” By the time Shah was a teenager, he saw Islam as “a hindrance to my freedom and autonomy,” he wrote in the introduction to one of his books.

Many Muslims seemed to focus on outward observance, such as performance of daily prayers, Qur’anic recitation, dress codes and dietary restrictions, he noticed. It seemed like a religion of rules and regulations.

When Shah became a premedical student in college, he finally experienced the freedom he “so deeply longed for.” He indulged his habit of watching Western movies and became enamored with the Western World. In contrast, he noticed and was disheartened by the lack of Muslim names among the scientists and scholars in his textbooks. He began to associate Christianity and the West with progress.

Shah thought of Islam, on the other hand, as connected to the backwardness he saw in Pakistan. “Pakistan was established as the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. Its founding documents call it a Muslim land. I thought of Islam as the foundation of Muslim civilization and Christianity and Judaism as the foundation of Western civilization. What was happening in the U.S. in the late 1970s looked more advanced than Pakistan. That made me interested in learning more about Christianity and Judaism.”

Shah began meeting with a Catholic priest who gave him a Bible and discussed the Christian faith. “The Christian road to paradise seemed a lot easier than the Islamic one,” he noticed. This began an internal struggle that engaged Shah for years.

“During one of his surprise visits to my lodgings, my father happened to see the Bible lying innocuously in my room and was appalled. He began to insist I learn the Qur’an before exploring the Bible further and enlisted the help of some family friends to try and make me a conscious rather than a traditional Muslim. These individuals were more open than my parents to questions, discourse and debate.”

Thus began a long and intense period of questioning and research. Shah explored his questions with his father’s friends, all teachers. They found his questions too profound and sophisticated to address well and referred him to religious scholars in their district, Shah recalled. Meanwhile, Shah also met Christian missionaries and church leaders who also felt the need to refer Shah to scholars and theologians for the answers he sought.

For one thing, Shah wondered, “If Islam is from God Almighty and has divine wisdom incorporated into its scripture, why are Muslims unable to utilize that wisdom to bring human dignity, human rights and developments into the Muslim world? Why is the Muslim world a place of all kinds of persecution?

Muslim professors encouraged Shah to pursue studies at the International Islamic University in Islamabad, a new public research university that brought together major religious scholars from the East and West. He began in 1981.

That was the beginning of his studies of the fundamentals of Islamic religion with a specialization in comparative religion and the beginning of learning the Arabic language. His professors were from Al Azhar University in Cairo (the world’s most prestigious university for Islamic studies), from Saudi Arabia, and leading Western universities – Oxford, Cambridge, Columbia and Temple.

“That’s where I came across Professor Anis Ahmad, a graduate of Temple University and a student of Ismail al-Faruqi,” a trailblazing Islamic scholar, “one of the known intellectuals in the Muslim world.” Professor Ahmad “was the person who resolved many of the questions I had about Islamic and Christian civilization, and about the Western and Muslim worlds.

“I dedicated my latest book to him,” Shah added, pointing out the dedication in his almost 700-page tome: “Dedicated to my teacher and mentor Professor Anis Ahmad—with utmost respect, appreciation and love.”

Shah calls his time at IIUI “the most productive and foundational years of my life.” It was a heady time. He was surrounded by world-class scholars who found him to be an exceptionally bright student.

“I had learned Arabic. I was good at English. I was doing translation work that brought me a lot of money and gave me the opportunity to meet some ambassadors and Royal families when they visited Pakistan. I started making a lot of connections. I started thinking I’m special, exceptional. I became very ambitious.

“I was delving deep into the Qur’an and it was like an ocean. I was just mesmerized. Then I started studying Christian and Jewish history, and modern philosophy. It was another ocean. I did not have time for anything else. I felt, ‘This is my life.’”

Shah received his Bachelor of Arts and Master of Arts (with honors) in Comparative Religions from IIUI. With encouragement and support from his professors, Shah accepted a position as a full-time lecturer in IIUI’s Comparative Religions Department and pursued academic life. IIUI would pay for him to complete his doctoral degree. He won admission to Harvard Divinity School to pursue a master’s and doctorate degree but that was not to be.

Part 2: Facing death

On the way to the airport to begin his studies at Harvard, Shah was in an accident that put him on the brink of death. A head-on collision left him paralyzed from the neck down for two years.

“Suddenly everything was lost,” Shah said. “Unable to move any part of my body except my head, I was left wondering about my destiny. Long months of complete helplessness, sheer dependence upon others and a sense of total despair brought me face to face with the ultimate questions I had hitherto shrugged off—What was this life all about? Where did I come from? What was the purpose of my existence? Who was directing my life affairs? Where was I headed? What was true happiness?”

Staring at the ceiling in a lonely hospital room for long, tiring months, “many thoughts—worthy and unworthy—crossed my mind,” Shah wrote. “Why would Allah, the Most Merciful and Compassionate, strike me with such a dismantling blow? How could I beseech Him to give me another chance, curing me of this disability?

“Was it a result of me not searching for the true God? Could Jesus be the true God and save me at this difficult juncture of my life? Whom should I call to?

“There were times when these mere thoughts bothered me a great deal. I felt I was committing shirk (the sin of idolatry) by associating partners with the One and Only Allah.

“What about my degrees, articles and everything else I had cared so much about? Were they of any use to me now? All these theories about the origins of religion and God, discussions on atheism, agnosticism, relativism, pragmatism and skepticism at once became utterly irrelevant.

“Suddenly the issue of life after death became of great interest. I sincerely promised to myself and God that I would truly search for the meanings if given the chance.”

After two years, Shah made “a slow but miraculous recovery,” he said. “I was able to stand, to walk.” He decided to make good on his promise.

Part 3: Finding answers

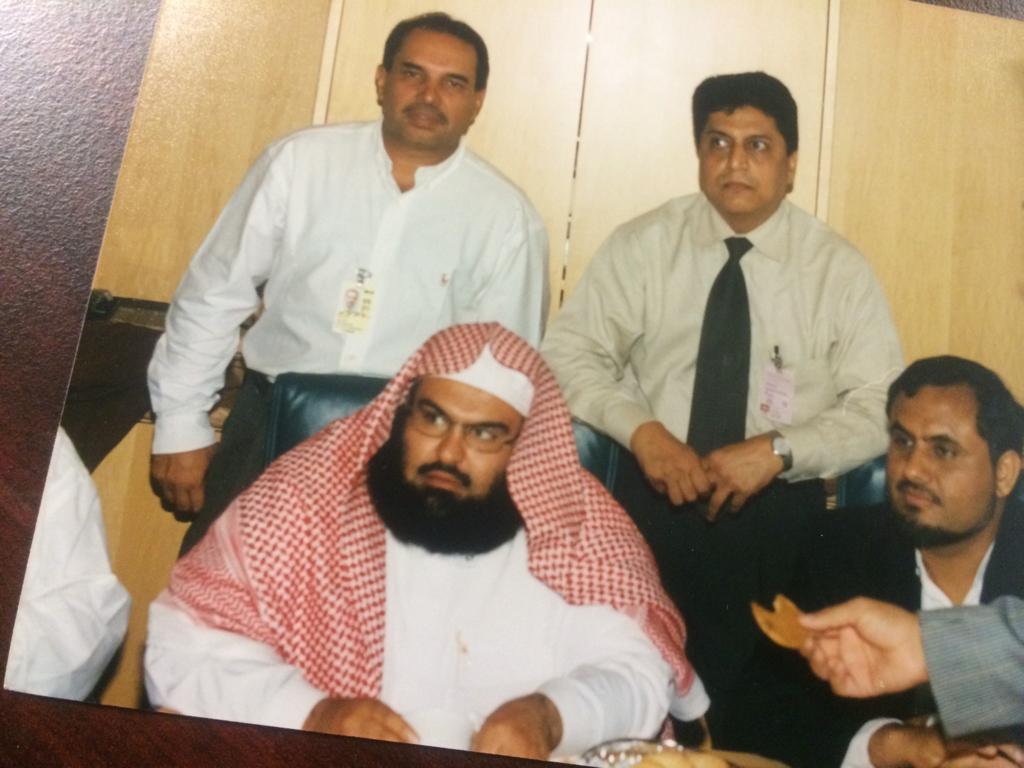

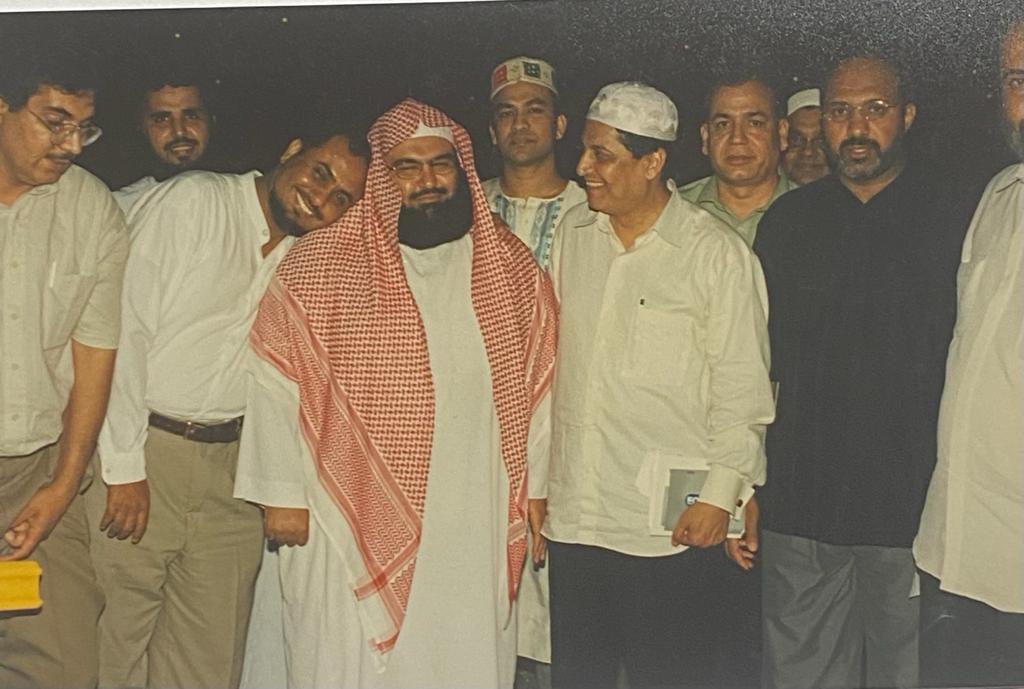

As the president of the Islamic Circle of North America (ICNA), Dr. Shah invited the imams of Al Aqsa, and Mecca and Medina to its conference and to travel together in the United States. Both imams visited South Florida where Shah lived.

Shah applied to the University of Wales, “mostly because of its strong theology program and teaching opportunities,” he said. There he worked with Professor Paul Badham, a renowned Christian theologian and son of Leslie Badham, the vicar of Windsor and chaplain to Queen Elizabeth of England.

“This scholarly soul made it clear to me from the outset that objectivity (not subjectivity) would be the ruling standard,” Shah recalled. “No claims were to be made without proper documentation and substantiation.” The sensitive nature of the subject demanded a methodology completely free of bias, prejudice and bigotry, he said.

Shah worked for seven years on this dissertation which later became one of his major books, his 2012, Anthropomorphic Depictions of God: The Concept of God in Judaic, Christian, and Islamic Traditions: Representing the Unrepresentable. He hopes it “will generate positive scholastic debate and dialogue between followers of the three Semitic traditions,” Judaism, Christianity and Islam.”

Indeed, leading scholars took note. “Scholars dealing with concepts of God in the three traditions will have to come to terms with this work in the future,” Harvard Divinity School Dean William A. Graham says. Georgetown University Professor of Islamic Studies John L. Esposito calls it “a masterful, thought-provoking and insightful study.”

Sheikh Hamza Yusuf Hanson, one of the most influential Islamic figures in the Western world and co-founder and president of Zaytuna College in Berkeley, California, the first accredited Muslim liberal arts college in the United States, credits it with bringing attention to “an extremely important topic” that “many of the greatest theologians have missed.” King’s College London Professor of Christian Doctrine Oliver Davies calls it “a major contribution … to the ongoing conversation between Islam and Christianity.”

Shah continued to work in universities, moving to the University of North Florida.

Part 4: Creating a faithful life

Photo by Cherrie Hanson

Dr. Zulfiqar Shah is often found in his office at the Islamic Center of Milwaukee.

The academic life had its limitations, Shah discovered. To pursue research, one needed funding that often limited the questions one could pursue, he said.

“I had an intention to do something for the sake of eternal life while working in this world. In the university environment, grants were reserved for popular issues like the rights of women in Islam, or LGBTQ rights, or freedom of religion in the Muslim world, or the rights of different minorities. This was not my piece of the cake. My interests were on civilization issues, intellectual issues and theological issues.”

Likewise, “people did not like to go deep into a theological discussion. They’d tell me, ‘You need to go to seminary, or go talk to a bishop or rabbi.’ And in the classroom, most of the undergraduate students will take a course on religion but it is not their major. They just want to pass.

“I began to feel my impact was only on the 20 or 30 students in my classes who were the least interested in the topic. So, I decided to make the full transition from academic work to Islamic work, joining the Islamic Center of Northeast Florida.”

ISM director Othman Atta recalls that ISM hired Dr. Shah as religious director in January of 2006 “largely because of his background. We felt he can do more than the work of an imam. He can work with young people, educational programs, activism and outreach.

Photo by Mouna Photography

Dr. Zulfiqar Shah spoke for Palestinian rights at a rally in Milwaukee in May.

“Knowing that he is part of the Fiqh Council of North America is also a benefit to our community, having access to that level of knowledge and information,” Atta said.

“One thing about Dr. Shah, with the level of knowledge he has, is that he is willing to think outside the traditional box. He doesn’t blindly repeat traditional teaching. He is willing to look at issues through a different lens to create new realizations, like they did during the Golden Age of Islam.”

The good news is that Shah’s lifetime of research brought him many of the answers he was seeking and he is eager to share it with others. Shah especially hopes it will also speak to young people, he said. The reading may get complicated, he warned. “My advice is don’t get stuck. Just keep moving because you will get the gist of what I’m saying. You don’t have to understand every argument.

“If you look at my life journey, it is the life journey of many Muslims. Muslim youth today are asking the questions that I did: Why shall I be a Muslim?”

His extensive writing argues that the success of the West has been largely supported by the influence of Islam on Western thought.

“I came to the conclusion that the present decline of Muslims had not been due to Islam but rather to (Muslims) betrayal of it. Islam cannot play second fiddle in our lives but requires sincere devotion.

“One of the symptoms of this decline has been the intellectual bankruptcy of Muslims, encapsulated by a centuries-long stagnation in Muslim critical thinking. For far too long now, the faith’s religious leadership has sought to punish thinking outside of the box, without regard for the serious socio-political consequences.

“I realized that if Muslims adhered sincerely to the teaching of the Qur’an and the Qur’anic principle of using reason, then Allah would support them just as He has done in the past.”

Photo by Cherrie Hanson