Julia Jacobs as “A Sound-and-Art Show Fills a Void for Muslims in Brooklyn” for The New York Times

Nsenga Knight, a 38-year-old artist, recalls visiting the Brooklyn Historical Society archives after receiving a research grant, curious to explore what sort of material she could find about Muslims in Brooklyn. She didn’t find much of anything.

“They’re missing a lot of stuff,” Ms. Knight, who was raised Muslim in the East Flatbush neighborhood, thought. “There were hardly any images of Muslims in their archives. They didn’t have that many images of black people.”

“The archive of Brooklyn isn’t necessarily representing Brooklyn,” she concluded.

Recently, that has changed drastically.

Oral historians associated with the Brooklyn Historical Society spent last year traversing the borough, recording interviews with dozens of Muslims. The intention was to preserve the conversations to fill what the institution admits was a gaping cultural hole in its famous archives.

They collected 54 oral histories, which amount to over 100 hours of audio, publishing the conversations online for public listening. Many interview subjects were born and raised in Brooklyn. Others immigrated here from about a dozen countries, including Pakistan, Morocco and Trinidad and Tobago.

They come from a variety of religious sects, including Sunni, Shiite and the Nation of Islam. They discuss everything from the social dynamics in their families, marriages and mosques to the repercussions after the Sept. 11 attacks and the most recent presidential election.

On Saturday, the Brooklyn Historical Society opened a sound-and-art exhibition drawn from the oral history project that includes a series of black-and-white geometric prints by the Brooklyn artist Kameelah Janan Rasheed. The installation is titled “An Opening,” a reference to the first chapter of the Quran, called Surah Al-Fatiha.

But engineering a space for viewers to explore the exhibition independently while listening to intimate interviews posed a technological challenge, Ms. Rasheed said.

Their solution was to provide visitors with headphones and iPod Touches that attach to lanyards around their necks. The iPod Touches have a newly created program that recognizes 11 of Ms. Rasheed’s larger prints. When visitors walk in front of a print, the program sets off an oral history chosen by the artist. As they walk between the prints, they hear a patchwork of overlapping voices — a murmur, a snippet of speech, a laugh.

“It’s like you’re tuning channels on a radio,” Ms. Rasheed said, “The goal is to invite people to linger in some places, but to give people the option of doing a survey of the space.”

Ms. Rasheed, 34, chose stories that drew her in. At one print, a Brooklyn-born man in his 40s discusses the uniquely African-American Muslim tradition of the bean pie. At another, a woman recalls a childhood in which everyone in her social circle was Muslim, making her feel as though she grew up in a “Muslim country.”

Because the storytelling in the oral histories is anything but linear — the narratives tend to stop and start and jump around throughout the person’s life — Ms. Rasheed reflects that concept in her exhibition, which often travels off the frame and into the space in between the prints.

Ms. Rasheed, who grew up in East Palo Alto, Calif., was raised by parents who converted to Islam. She is particularly drawn to narratives about Muslim history and identity that don’t often get mainstream attention, like the story told by Ms. Knight, who was ultimately interviewed for the project, and spoke of celebrating the Eid festivals, two important Muslim holidays, in Prospect Park as a child.

“There’s an assumption of a homogeneous Muslim identity,” Ms. Rasheed said, “As a person who grew up in an African-American family and who is also Muslim, people forget that we exist at all.”

The exhibition is one piece of a broad effort by the Brooklyn Historical Society to create an archival presence of Muslims, who comprise about 4 percent of the borough’s population, according to a 2016 analysis by the Public Religion Research Institute.

Deborah Schwartz, president of the Brooklyn Historical Society, said that the institution was established in 1863, and for over a century the archives mostly reflected the backgrounds of the white men who founded it.

“Before this project if you had come to the Brooklyn Historical Society to do research about Muslims or any topic related to Muslims, you basically would have found next to nothing,” Ms. Schwartz said.

Throughout the past two decades or so, she added, the organization has made a concerted effort to fill those gaps.

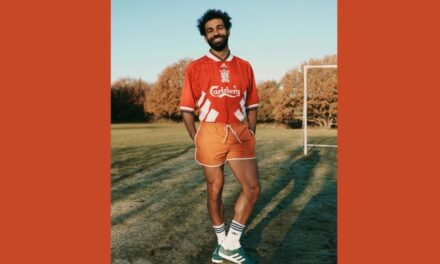

Credit: Christopher Gregory for The New York Times

The idea for this project came from Zaheer Ali, a scholar of Muslims in the United States, who was hired as the society’s resident oral historian in 2015 and drew on his ties to Muslims in Brooklyn to compile an extensive list of potential interview subjects.

There was a point where Ms. Schwartz said she and other staff members questioned whether the project was still viable. It was when President Trump won the 2016 election after proposing to ban Muslim immigration to the country. Ms. Schwartz said some Muslims in New York City had serious concerns about surveillance in their communities; others were worried about losing their immigration status.

But after consulting the board of trustees, she said, “We all agreed it was perhaps more important than it even started out as.”

“We wanted to make sure that people felt some sense of trust,” Ms. Schwartz said, “that if they were going to lend us their stories, that they understood this was a responsible, safe place to talk about their lives.”

The “Muslims in Brooklyn” project became much more than a collection of interviews that would be tucked away in the institution’s archives. The historical society organized community listening sessions for the interviews and developed a free educational curriculum for schools. A second art exhibition at BRIC House, opening Sept. 12, presents the work of eight artists (including Ms. Knight) and focuses on “multiple dimensions of the contemporary Muslim experience.”

Baseera Khan, another artist in the BRIC exhibition, also recorded a two-hour interview recounting her upbringing in Denton, Texas, by Muslim parents who immigrated from India. Ms. Khan said she grew up “afraid of being Muslim,” until she moved to Brooklyn in 2007, where there were Muslim residents all around her.

“Religion and spirituality and the acknowledgment of ancestry and all of this — it’s a thing now,” Ms. Khan said in her oral history. “But when I was in school, if you even had an inkling of interest in religion, people would shut you out.”

In different interviews, a man talked about the New York City Police Department’s targeted surveillance of Muslims after the Sept. 11 attacks. A woman spoke about the work that she had done to build interfaith relationships between Muslims and Jews in Brooklyn, and another about designing clothes that embrace religious modesty.

Ms. Rasheed drew inspiration from the oral histories while digging into her own family background. Hers is an interdisciplinary art that often juxtaposes scraps of academic text photocopied from books and reordered to give it new meaning. (Reviewing her work in a group show in April in The New York Times, Jillian Steinhauer wrote that the work formed “different permutations, suggesting a refreshing inquisitiveness.”)

To compile those disparate parts into something whole, Ms. Rasheed arranges shapes and text on the bed of a Xerox machine, manipulates and enlarges it digitally and prints it out on large sheets of archival inkjet paper. (She has two Xerox machines at her apartment in Crown Heights.) When she visits her parents’ home in California, she often goes through her father’s decades-old notes on the Quran and other Islamic books, taking home material that could one day fit into her art. Her father, who converted to Islam in the early 1980s, photocopied pages from the books and pasted them on white paper so he could annotate them without sullying the actual pages. Text from those notes, as well as Ms. Rasheed’s own Arabic study book from when she was a teenager, found places in “An Opening.”

Mr. Ali, the oral historian, said in an interview with a Brooklyn Historical Society curator that he and Ms. Rasheed had imagined an aural experience that was reminiscent of overhearing snippets of conversation from the surrounding tables in a cafe.

People who grew up in similar communities in one borough but who had never met had their voices overlaid, as if they were under one roof.

“We had created a community of people by forming this collection who didn’t know each other, who never said they identified with each other,” Mr. Ali said, “We did it to expand what people understood as being Muslim in Brooklyn.”