A large crowd gathered in Milwaukee March 18 in a rally against anti-Asian hate crimes.

Asian and Pacific Islander Heritage Month 2021 came on the heels of a mass shooting in Atlanta in March that left six people of Asian descent dead in a year when hate crimes against Asian Americans are up 150%.

It also saw the COVID-19 Hate Crimes Act signed into law. This law expedites the review of COVID-19-related hate crimes, makes online hate crimes and hate incident reporting language accessible, and expands the public awareness campaigns designed to increase awareness and outreach to victims. It “improves the overall infrastructure needed for hate crime reporting, data collection and justice,” said an article in the May 26 AAPI Vote Weekly Newsletter. AAPI Vote called the new law “a momentous step towards confronting the uptick in anti-Asian racism seen since the pandemic began.

“While we welcome this legislation, and believe it to be the most important civil rights bills for Asian Americans in American history, we also understand this is merely a step,” the article said. “We have to continue working towards eliminating the root causes of systemic racism, white supremacy and violence in the United States.”

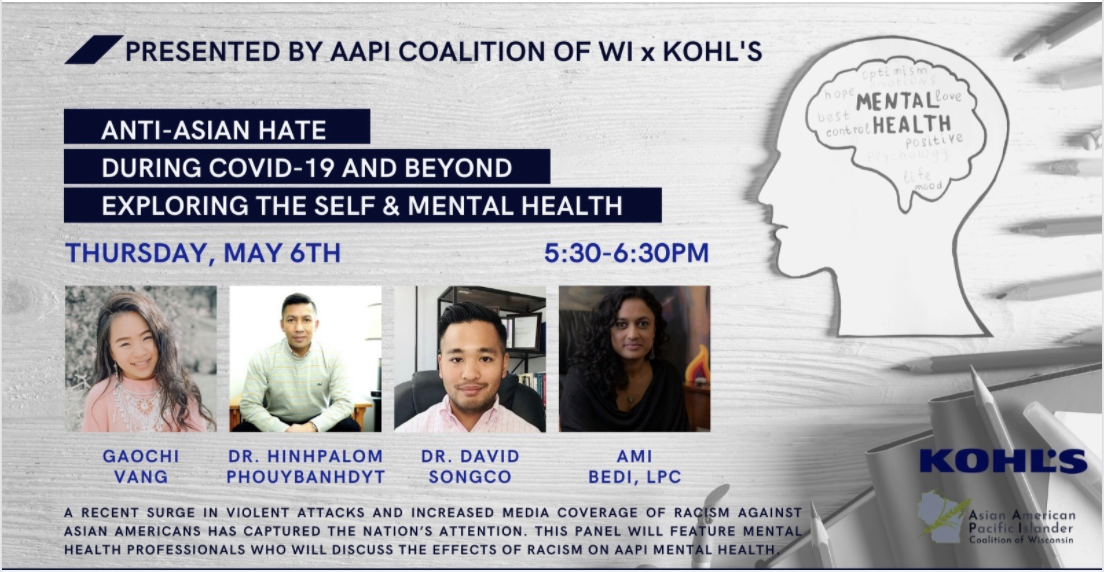

The AAPI Coalition of Wisconsin responded to the recent surge in violent attacks and negative rhetoric against Asian Americans by focusing on the mental health of the AAPI community throughout May, a month traditionally dedicated to celebrating AAPI culture and achievements. A panel of mental health professionals met May 6 to discuss the effects of anti-Asian racism, followed by four “healing space” sessions throughout the month for community members to share their experiences with others.

AAPI Coalition of Wisconsin and Kohl’s hosted a panel of mental health practitioners who discussed the psychological and social impacts of anti-Asian hate on the AAPI community.

AAPI Heritage Month’s history

A national commemoration of AAPI heritage began in 1979 when President Jimmy Carter issued a presidential proclamation calling for a week-long observance. It continued annually until 1992 when President George W. Bush designated the month of May as Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month.

May was chosen to commemorate two significant historical events: the arrival of the first Japanese immigrant on May 7, 1843, and the completion of the transcontinental railroad by the labor of tens of thousands of Chinese immigrants on May 10, 1869.

Since Carter’s presidency, every American president from Carter to President Joe Biden has issued a proclamation calling the nation to honor Asian and Pacific Americans. In 2009, President Barack Obama expanded the commemoration to include Pacific Islanders, renaming the month “Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month.”

Muslims have strong AAPI ties

Muslim Americans are closely linked to the AAPI community both through identity and common life experiences. Many Muslim Americans are in families with roots in Asian countries, including Indonesia, India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, among others.

In addition, both groups have experienced racial profiling, hate crimes and discrimination. Japanese Americans were dehumanized and interned during World War II, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The Sept. 11, 2001 attacks on the United States led to the scapegoating of Muslim Americans, who found themselves being expected to apologize for terrorism they had no part of.

The stereotyping that follow 9/11 has continued. FBI data shows that in 2015, there were 257 hate crimes against Muslims, the highest number since 2001.

Asian Americans have recently been the targets of a rash of violence that public health experts say resulted from the stigmatizing by President Donald Trump’s tweets that linked Asians to the COVID-19 pandemic.

These shared experiences have led the AAPI and Muslim communities to offer each other support. Muslims in Greater Milwaukee turned out for the vigil hosted by the Asian American Pacific Islander Coalition of Wisconsin in March, following the mass shooting in Atlanta.

“As the director of an organization that represents a large segment of the Muslim community, it was important to attend the rally to express solidarity with the members of the Asian American community,” Othman Atta, director of the Islamic Society of Milwaukee, explained to the Wisconsin Muslim Journal.

Imam Noman Hussein spoke at the AAPI Vigil held in March.

A month of healing

Throughout May, the AAPI Coalition of Wisconsin hosted opportunities for the AAPI community to reflect on how they are feeling about the rise in anti-Asian hate crimes and rhetoric. They began May 6 with the panel discussion Anti-Asian Hate during COVID-19 and Beyond: Exploring the Self & Mental Health, in which mental health professionals shared coping tools and personal experiences. It continued throughout the month with four “healing spaces,” opportunities for community members to share their personal experiences and stories.

Throughout the programs, participants shared stories of alienation and discrimination that dated back long before the current rise in hate crimes associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Panel members and community participants agreed that anti-Asian racism is much more overt, but that it is not new. They discussed the many challenges of being one of few persons of color in their schools or communities, balancing the demands of their collectivist family culture with the individualism of America and the sense of isolation felt among both their families’ cultures and their American peers.

Comfort in a “healing space”

Gaochi Vang, the assistant director of Iris Place, a peer-run mental health respite in Appleton, led the final community discussion of the month. It explored how storytelling can be a tool for AAPI identity development and addressed grieving, the healing process and personal growth. Vang described the process as “a journey we can do together.”

Vang, a Hmong American, noted that in communities like where she grew up in Wisconsin’s Fox Valley, “it was easy to feel invisible with its lack of representation and spaces for people to feel heard.” She said she found making spaces “for intentional listening” important for “grieving and healing with the community.”

Working with Fox Valley Hmong organizations, Vang said she is committed to aligning her passion for mental health care with opening spaces for the underserved to share their stories, to feel heard and to feel valued. She said, “The power of storytelling is where our mental wellbeing invites grief to come in and leads us to heal – with ourselves and with one another.”

During the “healing space session,” participants raised the following issues:

- A lack of media attention in the past and the feeling that no one cared about Asian issues;

- A conflict between “my Asian identity and my American identity,” feeling the need to choose;

- The need of Asian sons or daughters to meet parents’ expectations while crafting their own identities;

- Living a dual life – one at home and another out in the world;

- Stress from concerns about family members abroad;

- Being judged by appearance;

- Equating “white” with “American” and therefore not feeling American;

- Not being understood;

- Understanding more about how Black Americans feel, such as fear for one’s safety;

- Not feeling accepted by the Asian community because of “being too white,” not knowing the language or the nuances of the culture.

“We want to feel we belong, that we are loved, that we are cared about,” Vang said, summarizing the feelings expressed. “When we are not able to find that space, it is lonely.

“It is so much easier to tell people they are not alone than to show people,” she said. “Show them they are not alone by sharing your story and by being vulnerable with them.”

Some participants noted that the overt racism of current times feels “liberating.” News stories about the rise in anti-Asian hate made them feel “validated,” that the micro-aggressions they were feeling were “real.”

“Your experiences are valid, even when they have been swept under the rug,” said Vang. “And the micro-aggressions we felt, they are a big deal.”

Vang, who is also a poet and writer, shared a poem from her book Building Walls to Break Down that she said encapsulated her feelings about her Hmong American identity and healing with others (shown below).