“The government says they want us to ‘sinify’ our mosques, so they look more like Beijing’s Tiananmen Square,” says Ali, a Muslim farmer selling pomegranates outside the mosque. He requested that NPR use only his first name because residents have been ordered not to speak about the dome removals. “I think the mosque looks good either way, but what say do we have anyways?”

China is removing the domes and minarets from thousands of mosques across the country. Authorities say the domes are evidence of foreign religious influence and are taking down overtly Islamic architecture as part of a push to sinicize historically Muslim ethnic groups — to make them more traditionally Chinese.

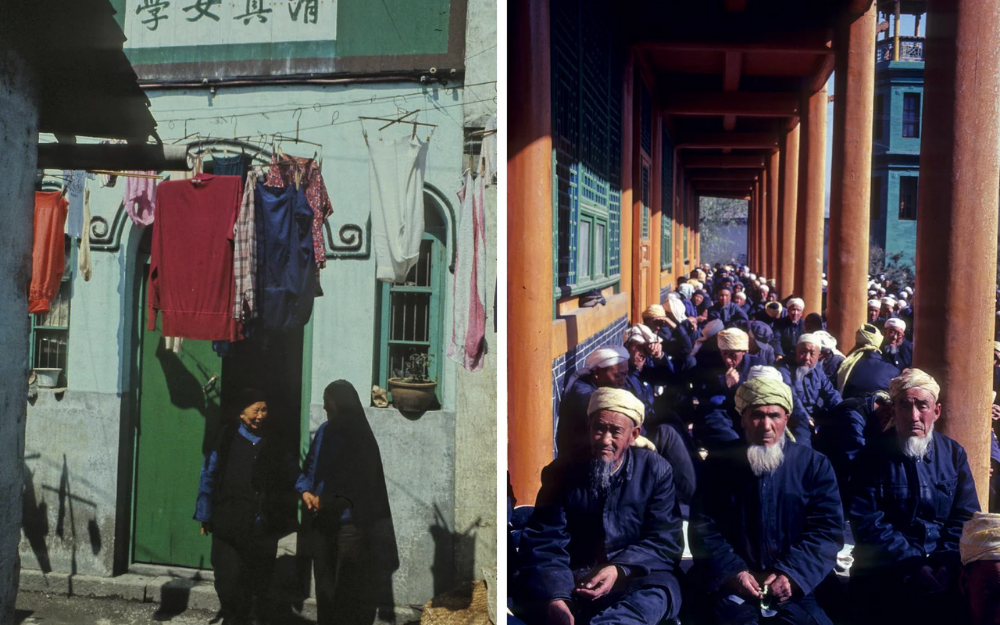

Xining’s Dongguan Mosque has been a source of community for Chinese Muslims for seven centuries. Here, Hui Muslim men pray in the mosque in 1983. Dru Gladney/Pomona College

The campaign comes amid rising Islamophobia in China and growing religious restrictions, touching off a discussion across the country among scholars, ethnic policy regulators and historically Muslim Chinese communities about what exactly should be considered “Chinese” to begin with.

China’s approach to ethnic minorities has shifted to “sinicization” under Xi Jinping’s rule

China’s ethnic policy is directly modeled on the Soviet approach, classifying citizens into 55 distinct ethnic minority groups, each of which, in theory, is granted limited cultural autonomy within its territory. But experts say the Communist Party under Xi Jinping’s rule has shifted to a new approach, one that favors integration and assimilation — a process dubbed “sinicization” in official speeches and documents.

“A very liberal or positive view of all this [sinicization] is just basically to compare it to, say, what’s it like to become an American citizen? You accommodate and people adjust,” says Dru Gladney, an expert on Islam in China at Pomona College.

The Dongguan mosque in September. China is removing the domes and minarets from thousands of mosques across the country. Authorities say the domes are evidence of foreign religious influence. They are taking down overtly Islamic architecture as part of a push to sinicize historically Muslim ethnic groups — to make them more traditionally Chinese. Emily Feng/NPR

After more than 1,300 years of living and intermarrying in China, Hui Muslims — who number about 10.5 million, less than 1% of China’s population — have adjusted by becoming culturally and linguistically Chinese. They even made their version of Islam accessible to Confucians and Daoists — trying to show it as inherently Chinese and not a foreign influence — by adopting spiritual concepts and terms found in ancient Chinese philosophy to explain Islamic precepts.

Various Hui sects have also incorporated Chinese religious practices into their worship, such as burning incense at religious ceremonies. Hui communities in central Henan province are even known for their female-only and female-led mosques, believed to be a uniquely long tradition in China.

The problem from Chinese authorities’ perspective, says Gladney, is that the Hui are not Chinese in the way sinicization proponents want: “When people make this one-way argument of sinicization, I think they’re confusing that with Han-isization” — in other words, making Chinese Muslims more like China’s Han ethnic majority.

Beijing has a much narrower understanding of what being “Chinese” means – adhering to Communist Party values, speaking only Mandarin Chinese and rejecting all foreign influence, say scholars.

Left: The entrance to a women’s-only mosque in the town of Jiaxing near Shanghai, in the 1980s. Female-only mosques were once common in Chinese Muslim communities. Right: Hui Muslim men in Xining’s Dongguan Mosque in 1983. Hui Muslims number about 10.5 million, less than 1% of China’s population. Dru Gladney/Pomona College

“The Communists nowadays try to culturally rule China,” says Ma Haiyun, an associate history professor at Frostburg University.

Authorities began taking down mosque domes a few years ago in an effort to remove “Saudi and Arabic influence”

The streets of Xining city in China’s Qinghai province are redolent with reminders of China’s historically multiethnic and co-religious composition. Many people wear the white cap or scarf favored by Hui Muslims, and visitors are equally likely to hear Mandarin Chinese as the Tibetan spoken by about a fifth of Qinhai’s population. Roughly one-sixth of the province’s population belongs to ethnic groups China classifies as Muslim.

At the heart of the city’s hustle and bustle is the Dongguan Mosque, Xining’s largest. In restaurants that crowd the alleyways around the mosque, vendors hand-pull halal beef soup noodles. Carts piled with dates and almonds cluster under brick archways.

But missing are the big green domes that once crowned its minarets and prayer hall. Under the slogan of “removing Saudi and Arabic influence,” authorities have torn down the domes from most mosques across China’s northwest as part of a national removal campaign that began in earnest in 2018.

Hui Muslim men in Xining’s Dongguan Mosque in 1983. In other parts of China, sinicization has allowed the state to justify the confiscation of mosque assets, the imprisonment of imams and the closure of religious institutions over the last two years. Dru Gladney/Pomona College

Xi first called for sinicization in 2016. In August, he gave a speech saying religious and ethnic groups should “hold high the banner of Chinese unity” — meaning they should put Chinese culture ahead of ethnic differences.

The dome removal campaign has met with limited public resistance. Xining residents say the Dongguan Mosque’s imam and director were briefly detained and forced to sign in favor of it. Less than a mile away, Xining’s marble Nanguan Mosque is also being prepped for dome removal. A shell of bamboo scaffolding encases its white dome.

“The local residents are spreading rumors,” said a man who declined to identify himself and tried to prevent NPR from taking pictures outside the mosque. Despite the removal of the Dongguan Mosque’s domes, he insists they are still in place. “Dongguan’s and Nanguan’s domes are preserved. Some might have been taken down for renovation.”

In other parts of China, sinicization has allowed the state to justify the confiscation of mosque assets, the imprisonment of imams and the closure of religious institutions over the last two years.

Dome removal preparations are under way at the Nanguan Mosque in Xining city. But China’s efforts at cultural control are most heavy-handed in the western region of Xinjiang, where authorities detained hundreds of thousands of ethnic Uyghurs in camps. Beijing says the camps are schools that teach the Chinese language and Chinese communist theory. Emily Feng/NPR

It has also buttressed simultaneous restrictions on the use of non-Chinese languages, such as Tibetan or Uyghur. In the province of Inner Mongolia, peaceful mass protests broke out last September but were quickly stifled after schools reduced the time devoted to teaching the Mongolian language in favor of Mandarin Chinese.

China’s efforts at cultural control are most heavy-handed in the western region of Xinjiang, where authorities detained hundreds of thousands of ethnic Uyghurs in camps Beijing says are schools that teach the Chinese language and Chinese communist theory. The state has also damaged or outright demolished thousands of Xinjiang mosques and religious sites.

Hui Muslims continue to adapt

The dome removal at Xining’s Dongguan Mosque has split China’s already fractious Muslim community, which is prone to sectarian divisions, according to Frostburg’s Ma, who was born in Xining and was raised around the mosque.

“If you remodel this mosque and create some chaos [among the Muslim community]. You already have different sects starting to rise in Xining … I think the government is trying to divide and rule,” says Ma.

The state itself is also divided over what Chinese mosques should look like.

In the 1990s, as China opened up politically, local leaders encouraged Persian Gulf states such as Kuwait and Saudi Arabia to invest money into massive infrastructure projects aimed at internationalizing the once-closed Communist country. More Chinese Muslim students were able to study abroad in Middle Eastern countries, especially in Egypt, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, and they brought back new ideas about Islamic architecture.

A scene from Xining in the early 1980s. The current sinicization campaign comes amid rising Islamophobia in China and growing religious restrictions, touching off a discussion across the country among scholars, ethnic policy regulators and historically Muslim Chinese communities about what exactly should be considered “Chinese” to begin with. Dru Gladney/Pomona College

As part of these modernization efforts, authorities also tore down centuries-old Chinese-style mosque roofs— including the ones which graced the Dongguan Mosque — and built Arabic-style domes.

In previous conversations Gladney had with local governments intent on adding domes to old Chinese mosques, “I was jumping up and down, saying, ‘don’t do it, don’t do it,'” he says. “You can build your dome and your new mosque next door, but preserve what you have here.”

The Hui Muslims, for the most part, have accommodated the ever-changing cultural pressures around them.

Yusuf, the Muslim owner of a store near the Dongguan Mosque selling Muslim head coverings and halal beauty products, says the Hui must continue to adapt, as they have for centuries, to survive. He requested that NPR only use one name because residents may face state retribution for speaking about religious affairs with foreign journalists.

“Everything changes from one era to another. During Chairman Mao’s time, they tore down all our mosques. Then they built them up. Now they are tearing them down again! Just follow whatever political slogan the country is yelling at the time.”

For the third time in under a century, the Dongguan Mosque is going through another makeover — and that’s fine with Yusuf.

“To the average person, Chinese style, Arabic style… we don’t care! Our faith does not exist in our buildings. It lies in our heart,” he says, thumping his chest emphatically.