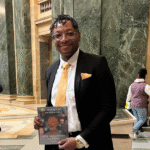

The lower-level banquet hall at ISM West was filled to capacity on Saturday night for a talk on “toxic masculinity” given by New York psychiatric resident Dr. Omar Shareef. The audience in Brookfield, about equally divided between men and women, seemed eager to take on the question of “What makes a man a real man?”

Shareef, who recently married into a Milwaukee-area family, admitted he had come here to give the talk because it is“becoming very difficult to do this kind of topic back in New York,” where it is seen as “anti-men, anti-manhood.” But he made it clear that he was “not attacking manhood, what it means to be a man. What I really want to focus on tonight is what hurts us as men and harms us as men.”

As a Muslim mental health professional, Shareef said he wanted to speak from “the core of where everything emanates from, the Qu’ran and sunnah” where he believes “the truth of what a real man is” can be found.

For Muslims, Shareef said, the best role models of healthy masculinity are the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) and “the one who is considered the most masculine of all his sahaba,” Omar Ibn Al-Khattab, “the kind of man . . . who instills fear in people when he speaks. His voice is like thunder, and men come to attention when he talks.”

Before explaining how these role models function, Shareef first asked the audience two questions: What is a Good Man? And what is a Real Man? He made lists on a white board of the answers. Both men and women put their own spin on the questions.

A good man, the audience said, was pious and family-oriented, a provider as well as a good listener. A real man was tough, “take charge,” and responsible. Shareef kept probing until one man finally said a real man is “emotionless.”

Shareef agreed. “If someone tells me to ‘man up,’ what they’re telling me is I am weak, and you need to be strong, you need to be stoic. The word stoic means ‘emotionless.’ If I’m telling you to man up, I’m telling you to stop being weak, to show me strength, because a real man is a strong man. A real man is a tough man. A real man takes charge.”

An older woman from the audience said, “A real man can cry too. They have emotions too.”

“Bless your heart, sister. Masha’Allah,” Shareef replied.

He went on to explain that both internal Muslim family culture and external factors in American society determine what we believe a real man to be. He spoke about watching Will Smith in Bad Boys when he was in high school and admiring that version of masculinity, but also about being told by his mother not to talk to girls and being stigmatized as a result.

“All I need to do is show you guys the Top 10 on Billboard, look at hip hop and R&B and mumble rap,” Shareef said. “Watch the music video and tell me what you see. Where does power and control lie in the music video? With the man.”

However, Shareef said he “put a very heavy fault” on the culture within the Muslim family, where, he said, “there has been poison fed into” the definition of a man,and “it is packaged as Islam when it’s not.”

Muslim-American culture, Shareef said, puts a heavy emphasis on success. “What makes a successful man – making lots of money. And if you don’t have this, I’m sorry to say, you’re not a real man, you’re deficient. Something’s wrong with you. Your family is not blessed because you’re not providing the way a man should provide.”

As a result, Shareef said, “Paycheck dictates worth and paycheck dictates masculinity.” He gave a couple of examples of how men are viewed as a result, of the man who has a newsstand on the corner in New York City versus the successful businessman, the man who doesn’t make it into medical school and decides to become a physician’s assistant instead. “We’ve built a certain standard that is harmful to boys and men because it makes them feel less than others,” Shareef said.

Shareef, whose mother is Pakistani and father Indian, also gave some examples of how rigid gender roles affect women. The women in the desi family are always the ones who “make the chai,” who do the dishes and take care of the house, while the man is the one who is served. “For the sisters,” he said, “your value as a woman now gets dictated by the value of the man you’ve married.”

As for the children in this family, if they misbehave, Shareef said, they are told to “wait until Dad comes home. Dad represents anger, fear, control. When the dad comes home, he yells. What arsenal does the dad have? Emotional intelligence, nurturing? It’s not in the library of what constitutes a typical, traditional father.”

To counter these examples of toxic family values, Shareef said, “There is nothing more progressive than the Qu’ran and the sunnah in describing what a real man is.”

The Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) expressed his fears to his wife, asking her to “cover me,” during a difficult moment in his journey to Allah. He often sought emotional support and guidance by turning to his wives, which Shareef said “is a message for each and every one of us that this is what a real man is – a man who understands vulnerability and transforms it into strength,” one who is not afraid of his own tears.

As for Omar Ibn Al-Khattab, who grabbed a sword intending to kill the Prophet before his own conversion, the hadith describe him as lamenting “what he did in the past. The demons inside of him are not small demons – and he just lets it go. He transforms it into emotion and then expresses the emotion. The sahaba then cry with him. He is a release of emotions for other men around him.”

For Shareef, learning to acknowledge and express emotion by using the examples of both Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) and Omar Ibn Khattab, is the key to healthy masculinity, a solution to the typical male practice of coming home, sitting in front of the TV, and shutting down.

He asked men to acknowledge that “you are someone who carries weakness, pain, trauma. All of us do. Open it, let the channel flow. Seek help, open up, even if it is from a professional. Or seek help from the woman in your life and go into her embrace rather than run away and withdraw. If you don’t know how, learn, so that you can begin to express the emotion that you’ve kept inside.”

The audience at ISM West seemed divided into two camps by Dr. Shareef’s lively talk. The older woman who acted as spokesperson for her small group seemed to feel that she was already there, that she had taught her children to follow their passion and not the money, and that her men knew how to cry.

But a father had a slightly different take after the lecture and discussion. Luqman D., age 38, who carried his young daughter on his shoulders, said he didn’t want his eight-year-old son to grow up to “be a snowflake. I want to make sure he has strength.” As a father, Luqman sees himself as role model in finding a “careful balance. This is what our deen” requires, he said.