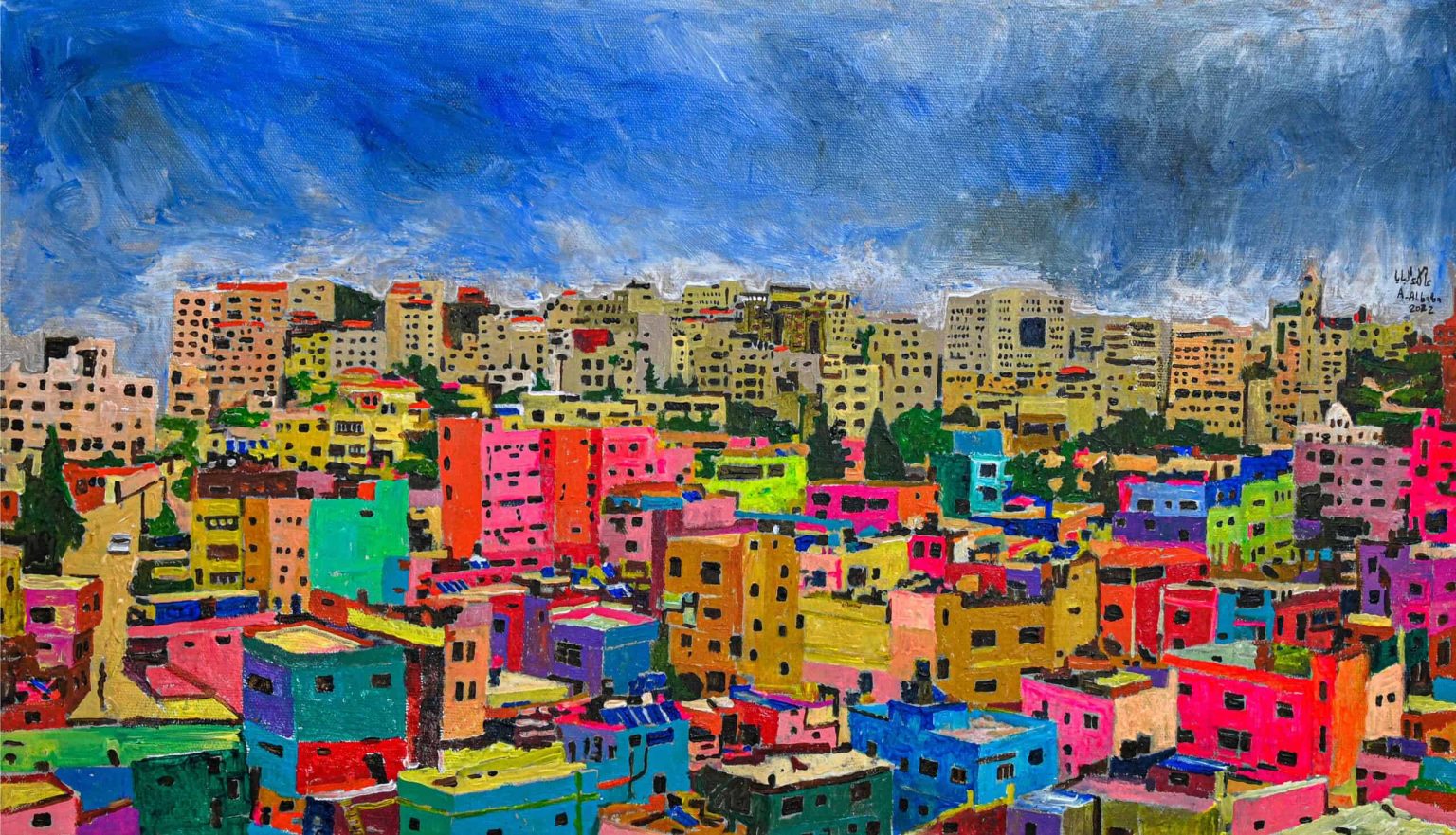

THE REFUGEE CAMP #8 BY ALAA ALBABA

Some people might suppose that 2024 was a bad year for Ahmed Hmeedat to launch the Palestinian Artists Consortium. The new venture is a “virtual venue” to see art and meet artists in Palestine and, if one chooses, to buy their works. But who can think about art, much less buy it, as the Israeli state’s apocalyptic genocide accelerates the physical erasure of Palestine and Palestinians? How would the conscience of friends of Palestine permit them to buy art rather than donate all they can to aid the millions of victims and oppose U.S. complicity?

But let us not forget that art stirs deep feelings that connect our imaginations to the lives of others distant in time, space, and culture. In this case, art is a strong counterthrust against the ongoing effort to dehumanize Palestinians by Israel and its steadfast ally, the United States.

Yusuf Abudi, a Palestinian American, thinks so, and he is now a partner in the Consortium project, which Hmeedat originated with the creative web developer Elias Amro.

Consider the impact of the art of Consortium artist Alaa Albaba, a resident of the Al Amari Refugee Camp in Ramallah-Al Bireh, which even before the current war frequently suffered deadly raids by Israeli Occupation Forces. In photos, the camp presents as a cramped and impoverished warren of dingy lanes and residences, webbed with drooping electric wires. In Albaba’s paintings, however, we see something else, as in the one inset here.

The camp is crowded, yes. Impoverished, no doubt – but teeming with life and human hope and joy, which we feel in the warmth of expressive colors and the way they billow up to the sky like a cloud bank of square balloons. They seem like dreams and aspirations rising from the rectangular residences on the ground and their inhabitants. Intellectually, we already knew that, even in miserable camps, life, love, and moments of happiness existed. But Albaba’s soaring images make themselves at home in our field of vision. The notion of camps as hosting nothing but rage and resentment is swept away by a vivid sense of people’s inner lives – and our common humanity.

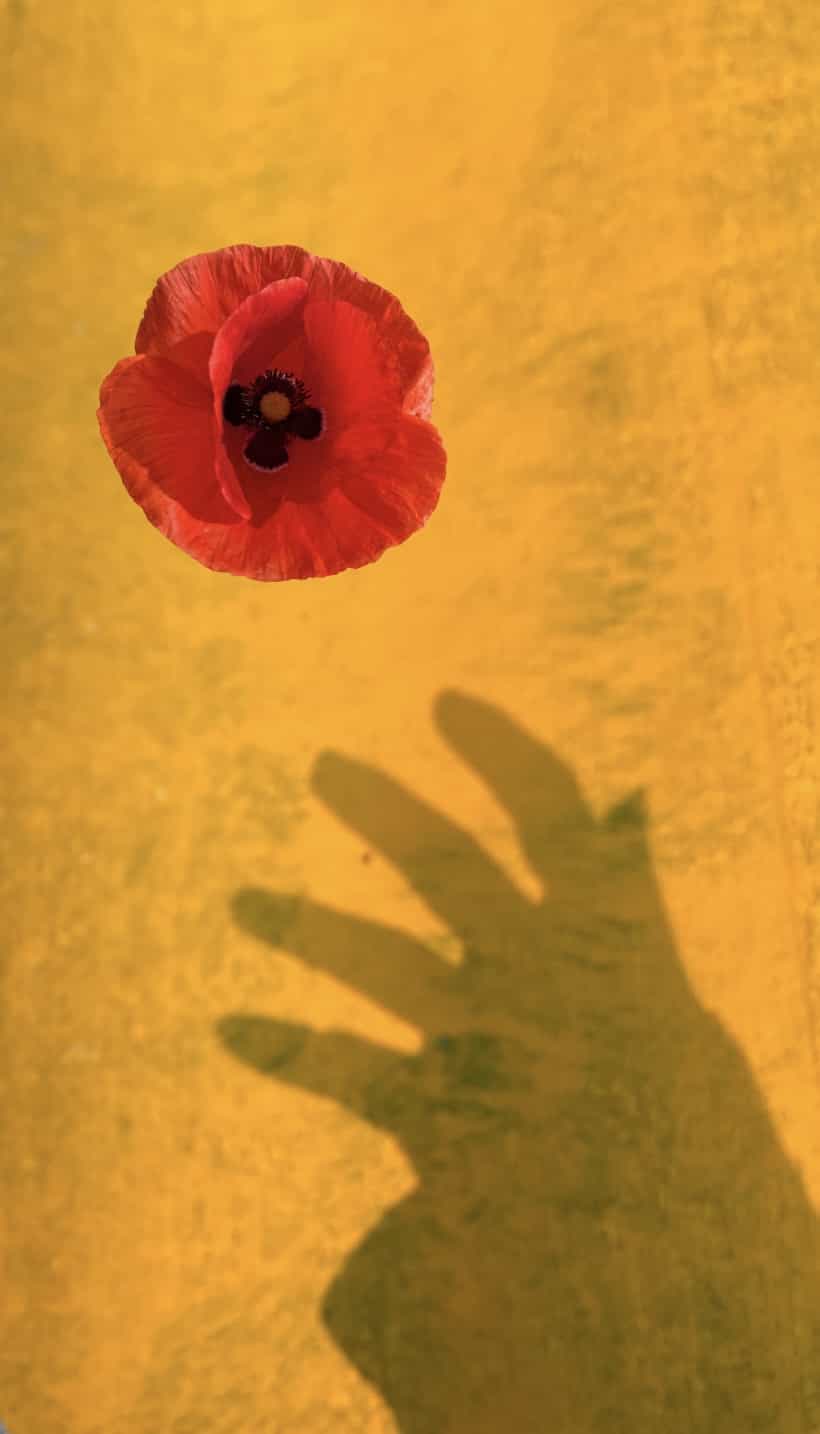

Photographic artists also find ways to shoot bittersweet arrows of human truth into the intimate recesses of our minds. Rehaf Al-Batniji of Gaza City focuses on “the street,” which in Gaza includes miles of glorious beaches. She composes images of color, light, the human form, and arresting visual details that convey the irrepressible beauty of life in Gaza before October, and the people’s deep attachment to the place. “I use my art to research reality,” she said on a recent Consortium webinar, as these two works show:

IN A LAND WHERE THE BLOOD OF THE ROSE IS A MARTYR, AND THE BLOOD OF THE MARTYR IS A ROSE BY REHAF AL BATNIJI

THE THREAD THAT CONNECTS THE CITY BY REHAF AL BATNIJI

As an artist, Hmeedat portrays a wide array of subjects in many media. His paintings often are witty and imaginative as in “The Trial II” :

The image captures the imagination. Here is the quiet, deliberate administration of justice, with the sun of beautiful Palestine pouring into the solemn courtroom, warming the pillars of international human rights law and giving immediacy to its imperative but often seemingly impossible application in Israel-Palestine. (The painting is exhibited at Ravensworth Baptist Church in Annandale, Virginia.)

In another painting, Hmeedat depicts the spirit of resistance in an original way: a wooden board, a big hammer – and a lively little bunch of nails that successfully dance away from the blows. Wildly imaginative, this visual sets one to thinking, hoping, and even believing that the arc of justice will bend toward the Palestinian cause.

Indeed, in creating the Consortium, Hmeedat is offering member artists a positive way to emerge from under the hammer of the Occupation onto what he calls “a free, global platform for Palestinian artists to professionally showcase their artwork and network, brainstorm, and sell their artwork to people who are eager to obtain authentic pieces.” Through webinars members directly connect with fellow artists, with the international art world – and the Palestinian public.

Only a few months since its launch, the platform already is receiving attention and exploring collaborations with art professionals in the U.S. and the U.K. More Palestinian artists are making contact with the idea of joining the project.

The Consortium doesn’t have specific criteria for choosing art and artists. “We don’t want to limit their creativity or narrow the range of art available to visitors and buyers,” Hmeedat says. “We look for artists who are eager to showcase their artwork, who are constantly producing, whether full-time or part-time.” The element of resistance can be more or less evident in the work, but it’s always there, baked into the lives of all Palestinian artists. “Just making art is resistance because it’s inherently about human dignity and flourishing,” Yusuf Abudi says.

The logo of the Consortium is a representation of the Palestinian Golden Eagle, which is an endangered species, with only one pair remaining. (Note the color of the eagle’s far-seeing eye, which gives a nod to the life-giving fruit of Palestine’s olive groves.)

“Our national identity is essential to the project,” Hmeedat explains. “It inspires in us a sense of collective effort and possibility.” He wants the platform to belong to the artists and for them to belong to the Consortium. So, members are invited to pitch in to help grow the project. One member is creating a poster collection; another has agreed to manage the Consortium’s social media operations. “We have momentum and the vibes are good,” he says.

On top of all that, the Consortium aims to use its artistic window into Palestinian realities, visible and invisible, to make Palestinians proud of their artists – and as a powerful tool of solidarity. Tolstoy wrote that art is “a means of union among men, joining them together in the same feelings, and is indispensable for the life and progress toward well-being of individuals and of humanity.” Never has this been truer – or more important — than with the art of Palestinians.