Fr. Owen Chourappa (center) with his team at LCHR (courtesy of Web site)

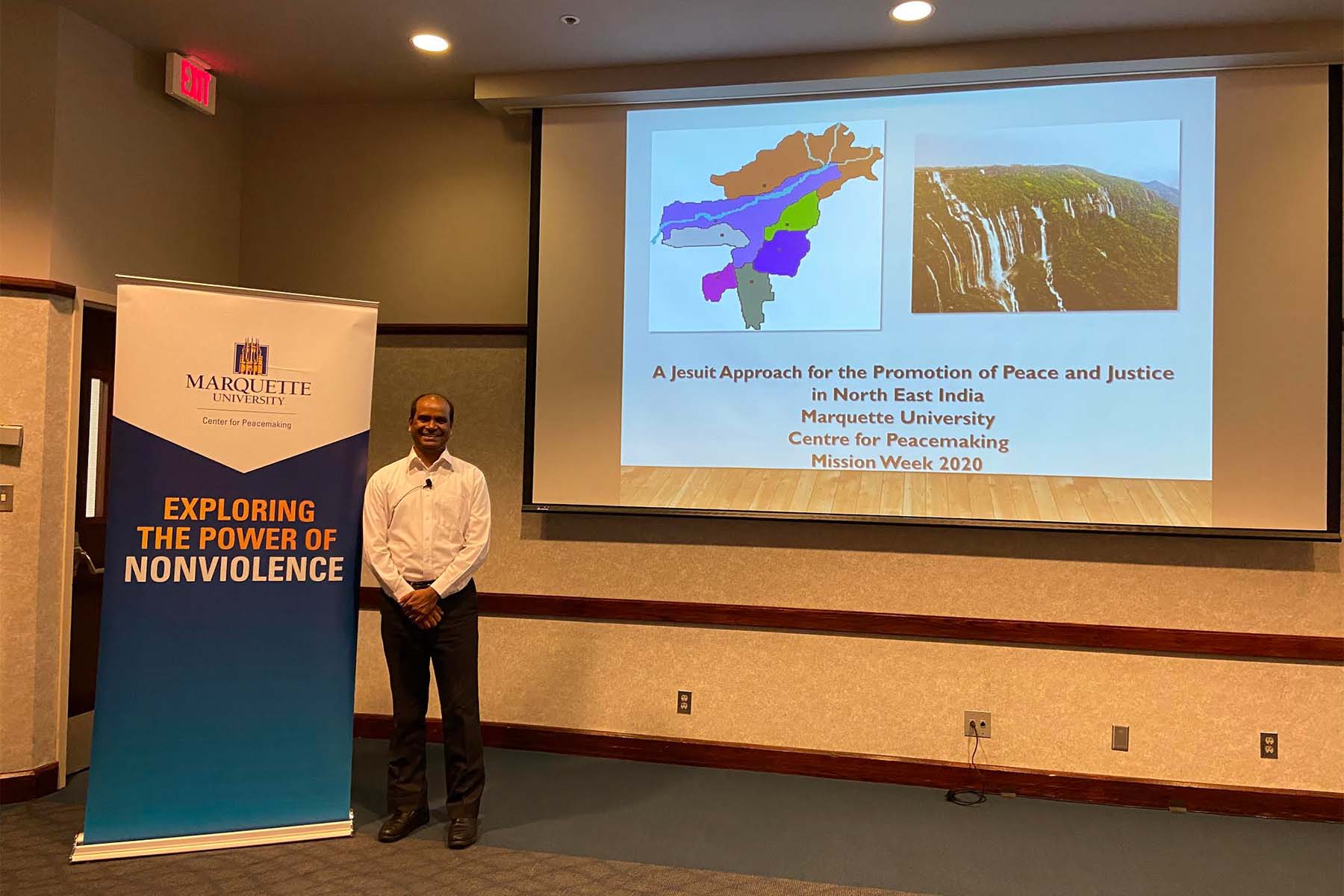

Fr. Owen Chourappa, SJ began his keynote talk at Marquette University’s Mission Week by placing his palms together and bowing slightly to his audience, a traditional greeting in his native India.

Fr. Chourappa’s visit was sponsored by Marquette University’s Center for Peacemaking. He traveled to Marquette from Assam, a remote state in Northeastern India where he directs the Legal Cell for Human Rights. Assam is home to many of the India’s famed tea plantations as well as some of its poorest people, the tea plantation workers.

Assam is also one of the centers of India’s current citizenship crisis, and a new set of policies aimed at Muslims, both residents of long-standing and newer arrivals.

Once a sparsely populated region, Assam saw its population grow in the 19th century, when British tea plantation owners imported indigenous labor to Assam from other parts of India. Even today, the province grows more than half of India’s tea, which is exported all over the world. Since the mid-1950s, newer migrants to Assam were created by war, famine, and poverty. Many of the new migrants live along the banks of the Brahmaputra River, the ninth longest river in the world, which flows through China, India, and Bangladesh. Most are defined as illegal because they entered India without papers, or, said Fr. Chourappa, lose their papers in the river’s annual floods.

An amendment to the Citizenship Act of 1995 passed by the Indian parliament in 2019 created a path to citizenship for refugees who are Hindu or members of Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi, and Christian religious minorities fleeing persecution in Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan. Since the 1970s, India has also been a refuge for Tibetans fleeing Chinese persecution.

But Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan are Muslim-majority countries. And Muslims were conspicuously left off the list.

As Fr. Chourappa told his audience at Marquette’s Alumni Memorial Union, many of the 1.96 million migrants “are on the verge of being taken to detention camps.” Unfortunately, said Fr. Chourappa, “our prime minister tells people there are no detention camps. These blatant lies are dividing people on religious lines.” Indian prime minister Narendra Modi and his BJP party have a well-documented goal of making India a Hindu nationalist country.

However, Fr. Chourappa believes that Hindu nationalism is “not the reality of India. The reality of India is not ‘us’ and ‘they,’ but ‘we the people.’” India, he said, has a constitution that provides for a “sovereign, secular government. It is not a religious state. This is not a fight of Muslims alone. It is the fight of a nation, of the identity of a nation” and of a “commitment to reconciliation and justice.”

The LCHR was founded in 1998 by the newly formed Kohima Jesuit Region in Northeastern India. The LCHR is “an initiative by the Jesuits of the Kohima Region” aiming to achieve a “strategic action-plan for social transformation of people of the Northeast India,” a transformation the Society of Jesus committed to in response to widespread poverty and illiteracy in the region.

The LCHR, said Fr. Chourappa, has thus far been able to help 600 people obtain representation in Indian courts that could put them on the path to citizenship.

Fr. Chourappa at MU (courtesy of Center for Peacemaking)

Fr. Chourappa’s visit was sponsored by Marquette University’s Center for Peacemaking, and his more relaxed style was reflective of his work in Assam, a remote state in Northeastern India where he directs the Legal Cell for Human Rights. Assam is home to many of the India’s famed tea plantations as well as some of its poorest people, the tea planation workers.

Chourappa’s legal team at LCHR is seasoned and could not be more grassroots, having been trained in the fight to bring tea plantation workers relief from grinding poverty through the application of rights they already had by law. It is comprised of the children of those same tea plantation workers.

The government of India has “wonderful social welfare programs,” said Chourappa, but they are often “not being implemented” due to corruption and ignorance. “India has been making elaborate plans in the form of development programs,” Chourappa said. But “they remain on paper and in files.” The people who should have been benefiting were often unaware that the programs existed.

Because of their grinding poverty, tea plantation laborers are subject to economic and sexual exploitation. Child trafficking and child slavery are common in an area where tea garden laborers live on wages of ₹167 (rupees) or $2.35 per day. They receive barely enough rice and tea to live on along with rickety, substandard housing. And even those ₹167 were “a raise given only after a big struggle, from ₹100” Fr. Chourappa said. “The fight is still on.”

The Jesuits saw a legal solution “to address the hunger of the people” and began teaching them about RIA, the Right to Information, Fr. Chourappa said. “We began to gather the people and teach them to ask these simple questions” of local officials.

India’s parliament had created a program for the poor that provides access to food ration cards. And yet, despite the ration cards, villagers continued to go hungry. One village youth trained in RIA asked, “How many people in my village have ration cards?” He was told that most of them did have ration cards. But then he asked, “What is the quantity of food distributed in my village?” And the answer to that question was, almost none.

As a result of being asked those two simple questions, the Indian government investigated and discovered that the agent in charge of distributing food to the villagers was selling it for his own profit. The agent was subsequently arrested. And the village began receiving more food.

Since 2005, over 150,000 tea garden laborers have benefited from the work of LCHR, Fr. Chourappa said. The organization paid 1,780 visits to 330 remote tea plantations and held 3000 sessions with tea garden workers.

One immediate result of this work was that the Society of Jesus was banned from entering the tea gardens. LCHR and the Jesuits were “not liked by” managers and owners of the tea gardens, as Fr. Chourappa calmly explained.

But this setback was the cause for more innovation of the part of the Jesuits of Kohima Region. They observed unemployed young people loitering around the tea gardens and trained them to be “paralegal persons,” also known as PPLs. Fr. Chourappa called them “barefoot lawyers,” who became agents of change in their communities. They were trained in the basics of law and sent back to their villages to continue the work the Society had begun. The only qualifications were the ability to read and write and the desire to be “socially motivated.”

The young PPLs received public speaking training and held a public awareness program each month at a tea plantation. “The work has been going really well,” Fr. Chourappa said. “Over the course of two years, 27,628 rural people became aware of laws and entitlements” that pertained to them and were “relevant for them to lead peaceful” and productive lives. “Legal empowerment” was a “crucial activity” to give them the “knowledge, confidence, and skills to realize their rights.”

As Fr. Chourappa said, “A right is not handed on a platter. It must be demanded.” And yet, as he emphasized throughout his talk, peacemaking is crucial to ending poverty. Fr. Chourappa connected his work in India to both Fr. Marquette’s mission to the indigenous tribes of North America, and to Mahatma Gandhi, who famously said, “Poverty is the worst form of violence.”