Photo Credit:

Courtesy of the Cornell Chapter of Amnesty International.

Milwaukee Muslims joined the Multifaith Initiative to End Mass Incarceration, a national interfaith movement launched in 2019 to expand work to end mass incarceration and look at the role of faith in this work.

Conversations among faith leaders are taking place in six places around country through this initiative: New York, Georgia, Arkansas, Texas, Southern California and Wisconsin. Leaders and members of congregations from various faith traditions who are engaged in jail and/or prison ministry and want to do more, and those who are ready to partner with faith communities to reduce incarceration rates in Wisconsin were invited to participate. The goal of these meetings is to coalesce around issues of mass incarceration to impact policy and offer support for people affected.

Wisconsin faith leaders met earlier this month with national faith leaders and public officials. Janan Najeeb, founder of the Milwaukee Muslim Women’s Coalition and member of the Islamic Society of Milwaukee, represented the Milwaukee Muslim Community.

Other local faith leaders included: Pardeep Singh Kaleka, executive director of the Interfaith Conference of Greater Milwaukee; Pastor Walter Lanier of Progressive Baptist; Lisa Jones, the executive director of MICAH; Sylvester Jackson from EXPO (Ex-Incarcerated People Organizing); Rev. Willie Briscoe, president of WISDOM; Rev. David Simmons, chair of the Interfaith Conference of Greater Milwaukee; Rev. Jack Murtaugh, a lifelong advocate and retired director of the Interfaith Conference; Rev. Joseph Ellwanger, author and lifelong civil rights activist; and David Liners, state director of WISDOM.

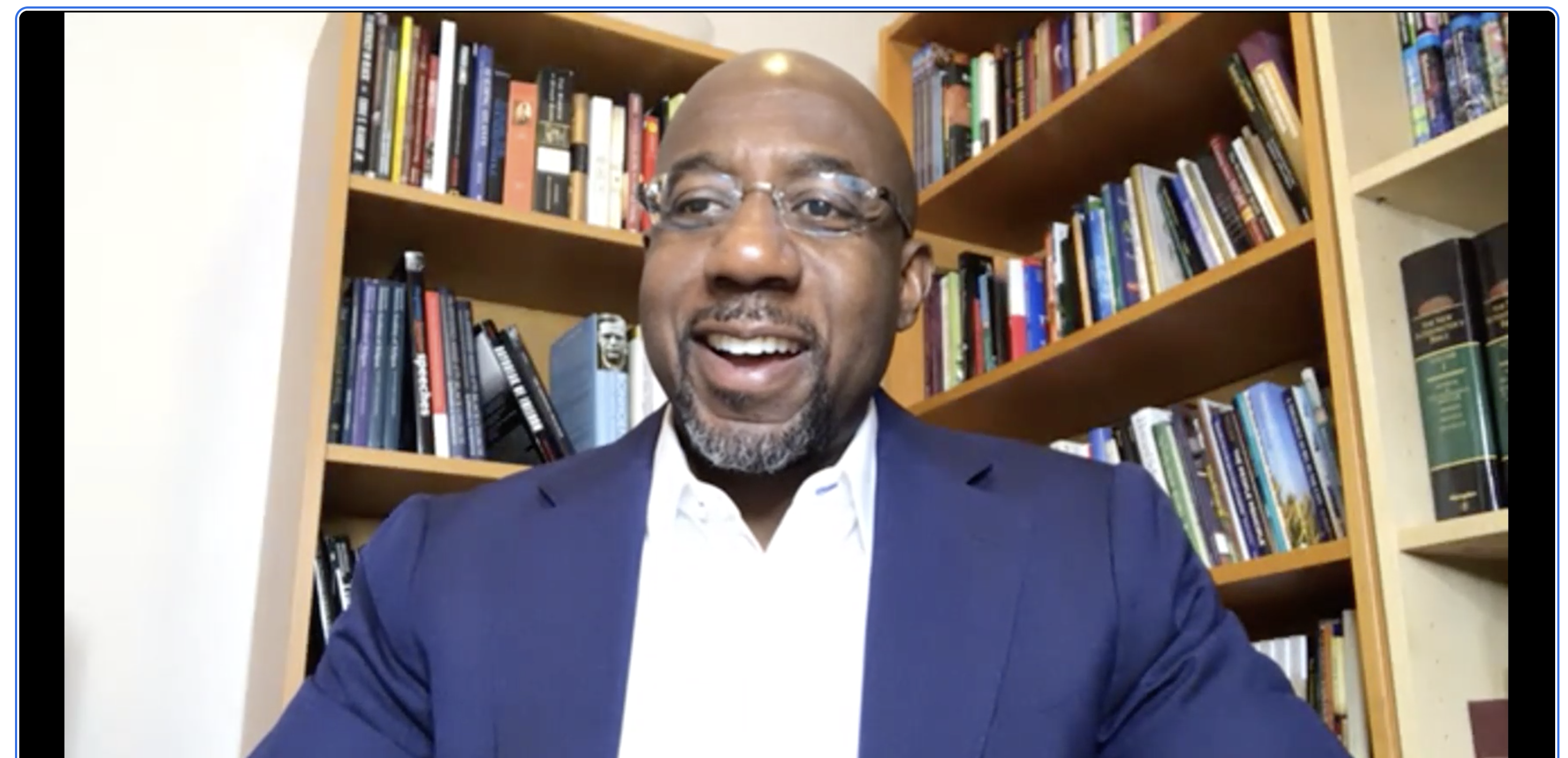

The national faith leaders and public officials at the July 10 meeting included featured speaker, newly elected Sen. Raphael Warnock (D-Georgia), who was introduced by Lt. Gov. Mandela Barnes.

Sen. Raphael Warnock on why fighting mass incarceration is important

“Jimmy Carter, a humanitarian and human rights activist, arguably achieved as much after he left the White House, proving that it is not about the position, but about the moral courage, and each of us in our own way can indeed make a difference,” Sen. Warnock said. “I am grateful for the way people in Wisconsin are stepping up.”

The Georgia senator would be going to the Carters’ home to celebrate the former president and first lady’s 75th wedding anniversary when he left the meeting, he said, by way of explaining why the Carters were on his mind.

“When Jimmy Carter left office in 1980 there were about 300,000 Americans in prison,” Warnock continued. “But over the 40 years since then, we have built in the land of the free an incarcerated state in which there are now 2.3 million Americans in prison.

“We are 4% of the world’s population, yet we warehouse 25% of the world’s prisoners. We have built this gigantic system. It is increasingly privatized. Its population climbed through Democratic and Republican administrations alike.

“A greater percentage of our Black population is in prison than was in South Africa at the height of apartheid.”

Warnock called mass incarceration “a central moral issue of our times. No matter what issue you are concerned about, this issue of mass incarceration is a good entry point – literacy, mental health, education, families, economic viability, women’s issues, voting rights – they all are impacted by mass incarceration.”

As the pastor at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, where Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., once served, Warnock explained that he feels compelled to fight against mass incarceration as part of continuing Dr. King’s fight for civil rights.

“Our criminal system is the one part of our society that is quantifiably more entrenched in the doctrine of white supremacy than it was before Dr. King marched down a single street,” he said.

He spoke about mass incarceration’s unfair impact on Black Americans. “Our children are scooped up on the street. Even as we decriminalize marijuana, we have grown ups who have been locked up for decades.

“Black and brown children are being treated differently. They are convinced to take a plea, thinking it is a light sentence. It is really a life sentence.

“They get marked with the stigma. All those discriminations Dr. King fought against for years are re-inscribed in that system. Once you are marked, job discrimination becomes legal. Voting rights can be taken even though you served your time. It is a life sentence for a petty crime.”

Warnock said he knows the pain mass incarceration causes personally because his brother, who was a police officer at the time, went to prison 22 years ago, at the age of 33, charged with “aiding and abetting in the war on drugs.” Prior to that he had not been convicted of anything, he said.

While he said he did not defend his brother’s actions, he noted that his brother was sent to a federal prison without even the possibility of parole. “There are no means of giving a murderer any more time than that.”

When COVID-19 spread through the overcrowded prison, his brother was sent home, but still under state control, Warnock said.

“Mass incarceration and police brutality are linked.”

“Police brutality is a result of our commitment to mass incarceration,” Warnock said. “When you build a beast this large, it’s got to eat.

“I am going to keep on doing this work because I have a son,” he continued. “He is only 2. I pray that when he is 16, I won’t have to teach him the lessons every Black mother, father, auntie and uncle knows they must teach – when you get pulled over by a police officer, keep your hands on the steering wheel. Be polite. Say, ‘Yes, mam’ and ‘Yes, sir. Don’t do anything to escalate the situation. After you get home we will deal with it later.”

Warnock called for doing this work to fight mass incarceration with a sense of urgency. “When I get discouraged, I look at that tape of John Lewis crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge. A 23-year-old man and others building a multi-racial, multi-generational, multi-faith coalition of conscience at an inflection point in our country to push us closer to our democratic ideals.

Sen. Raphael Warnock

Wisconsin leaders react

Lt. Gov. Mandela Barnes: The fight to reduce the prison population here in Wisconsin is not new and it is not news. There is so much work for all of us to do.

Interfaith Conference Executive Director Pardeep Kaleka: If we are to be honest with ourselves and our past, especially in this country and in our state, in many ways, we have failed to truly live out our commitment to loving one another from the core of divinely existence. There is no better example of this then our failing criminal justice system and our over reliance on punitive sentencing.

We have not worked hard enough on the front end to address the root causes of what we may deem as maladaptive or criminal behavior. And instead of looking at ourselves and reflecting on our failing institutions and policies, we point the finger and double down on the indignation and present that indignation as righteousness.

Today, we specifically call on the lifting of voices dedicated to building a theology of restoration and fairness in our Wisconsin legal system so that we can once and for all end the plague that imprisonment is having on individuals and families at large here in the state and across the US.

Lisa Jones, lead organizer for MICAH MKE: I had a brother who had addiction and mental health problems. He is no longer with us. I wonder if his life would have been different if we had treatment courts. We have to dream of a society that isn’t here yet. Wisconsin doesn’t have to remain the worst place to raise a Black child.

Sylvester Jackson, lead organizer of Expo (ex-incarcerated people organizing in Milwaukee): I have witnessed the inhumane treatment of other human beings, including myself. From 2007 to 2017, I was incarcerated. I’ve seen individuals die because they were refused medical treatment, I’ve seen people lose limbs. I couldn’t ignore what I witnessed.

David Simmon, chair of the Interfaith Conference of Greater Milwaukee: The thing we all have in common is respect for the inherent dignity of every human being.

The connection from slavery to Jim Crow to peonage (the use of laborers bound in servitude because of debt), to redlining (to refuse a loan or insurance to someone because they live in an area deemed to be a poor financial risk), to mass incarceration—it is obvious there is a clear line drawn through American history.

It is going to take all of us insisting that our civil discourse has to address the dignity of every human being. That we cannot stand for this race-based mass incarceration.

Rev. Willie Brisco, president of WISDOM: I was born in Mississippi, 68 years ago. I saw when larceny, littering and public drunkenness used to sentence people to fulfill a workforce that was not paid, the unpaid labor in the Jim Crow South.

I worked for 25 years in a correctional institution. It opened my eyes to how people are put away a in a place where they could not use their talents and gifts.

Next steps

A Congregational Expungement Training will be provided for Wisconsin participants Aug. 4 at 4 p.m. CT via Zoom. It will prepare faith communities to learn what they can do to help expunge the records of formerly incarcerated people to remove obstacles to work, housing and other matters they face. It aims to move communities “closer to restorative justice rather than retributive justice.”

Local faith leaders are also urged to develop fair processes to support the re-entry of formerly incarcerated people into the community. The Milwaukee Islamic Dawah Center’s Ibrahim House is an example of a local faith-based re-entry program that supports people in finding jobs and housing, helping them get a foothold back into society.