Shortly after converting to Islam, then-Sgt. Khallid Shabazz struggled to find his way while his devout Lutheran family and fellow Soldiers questioned his move.

And with a few Article 15s for insubordination on his record, Shabazz, a field artilleryman at the time, wanted out of the military. Then, one day while training out in the field, an Army chaplain approached him and struck up a conversation.

“Honestly, it was like a revelation from God,” Shabazz said. “When it hit my ears, I knew that was what I was going to do in life. It was incredible.”

The Christian chaplain had told Shabazz, who was a teacher before he joined the Army, that he should consider being a Muslim chaplain. That way, the chaplain said, he could help other Muslim Soldiers in need of guidance. Shabazz later became a chaplain, and proudly wore his uniform with the Islamic crescent moon stitched onto it. The career change was a catalyst for him, as he went on to achieve several other goals.

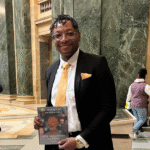

Currently a lieutenant colonel, Shabazz holds two doctorate degrees on top of four master’s degrees. He has written three books and teaches online courses at four colleges. He recently was chosen to study at the National War College, a rare feat for chaplains — only three of them are accepted each year. And last year, Shabazz became the U.S. military’s first Muslim division-level chaplain, a position he held with the 7th Infantry Division.

Shabazz was the lead chaplain of the 94th Army Air and Missile Defense Command here, but he has now surpassed yet another milestone with his promotion to colonel, which is the highest rank ever attained by a Muslim chaplain.

“It’s phenomenal first, but it’s unbelievable second,” Shabazz said.

BECOMING MUSLIM

Born as Michael Barnes, Shabazz grew up in a large Lutheran family in Alexandria, Louisiana. Once a faithful Lutheran himself, Shabazz often attended church and even graduated from a Christian college. His religious views changed in the Army when he decided to debate a Muslim Soldier on the merits of both religions. He admits he was ill-prepared for the debate and had misinformation about what Muslim people actually believed in. Afterward, he became curious about Islam and began to study the Quran.

“I didn’t want to convert; I was happy where I was,” he said. “I’m a very inquisitive person. If I don’t know something, I’m going to get to know it.”

While Shabazz found more peace and solace by switching faiths, which included the Islamic custom of changing his name, many people in his life stopped talking to him. His commander at the time, Shabazz said, even asked why he sided with the enemy.

“I was so hurt by those statements,” he said.

He eventually came to realize it was a lack of understanding some people had with Islam, which he was also guilty of until he studied it. Islam is sometimes distorted by extremist groups, he said, similar to how other religions can be twisted to incite violent acts.

“Whether it’s the Bible, Quran, or the Torah, I want people to understand that religion really has nothing to do with violence,” he said. “99.9 percent of the people in religion are good people.”

PROBLEM SOLVER

As a whole, he said, the Army has improved its inclusiveness of Islamic culture. Religious accommodations allow Muslim Soldiers to worship on Fridays and now give female Soldiers the option to wear a hijab and males to have a beard.

He also educates leaders and Soldiers about Muslim holidays and other traditions. For those struggling as he once did, he encourages them to pursue knowledge, too. Often, he receives calls from Muslims across the Army asking for help on issues or how to deal with blowback from others in their unit.

“What I ask you to do is, keep doing your job and keep working hard,” he said he tells them. “Go to school at night and stay focused on everything else besides the treatment.

“That’s coming from a person like me who went through that type of turmoil. I was an E-5 and I received some pretty tough treatment back then. I can tell them those stories and I think it helps.”

As a chaplain, he strives to inspire Soldiers to be successful, no matter their religious preference. To date, he has helped at least 70 Soldiers become officers and many other NCOs gain promotion points by taking college courses.

“I’m like a chaplain life coach,” he said, laughing. “I’m telling them don’t quit.”

While proud of his faith, he does not want to be known only as the Muslim chaplain — he is one of five currently in the Army. Unless a Soldier wants to talk about religion, he will leave those types of discussions at the door.

“I meet Soldiers where they’re at. I attack problems,” he said. “My job is not to be your spiritual advisor, your religious guru. I want to help Soldiers with school, with their family, their marital problems, and be almost like an arbitrator or a mediator.”

LIFE CHANGER

Years before, he had to overcome many of his own issues. In high school, he failed the 9th and 12th grades. He was not able to graduate with his class and had to go to summer school. His destructive behavior continued throughout his first stint of college, he said. When he was later able to get a job as a teacher, he made just under $19,000 per year.

So, he decided to join the Army as a 23-year-old private to take care of his wife and children. He also sought discipline and stability, which the Army could provide. As he initially thought it was a good idea to sign up, he admits it was a difficult change.

“I found myself getting into a lot of trouble. Having a 19-year-old sergeant cussing at you and telling you what to do didn’t go over very well with me,” he said, laughing.

Then that chaplain decided to stop and take the time to chat with Shabazz, who had just turned Muslim but still wrestled with his identity.

“I was at my lowest level and the chaplain came by and gave me what I needed at that point,” he said. “I wanted to dedicate my life, and I have, to helping people who are in that position. Not by converting them, but by being a person who can put their arm around them and try to help them get to the other side.”

Sean Kimmons

Claudio R. Tejada and Mike Selvage

Originally published as For Army’s highest-ranking Muslim chaplain, his calling came after years of turmoil