The roughly 800 Rohingya families currently living in Wisconsin have lives that other Burmese refugees can only dream about.

More than 850,000 Rohingya are crowded together in the world’s largest refugee camp, located in the Cox’s Bazar region of Bangladesh. The Rohingya were forced out of their homes in Myanmar (formerly Burma) by ethnic cleansing on the part of the majority-Buddhist government and its military. Their only means of protecting themselves against the spread of corona virus are frequent handwashing and coughing hygiene. Social distancing is impossible in a refugee camp.

In April, 32 Rohingya are believed to have died on a boat carrying more than 400 starving people that had been sailing around the Bay of Bengal for nearly two months, unable to make port, before finally being rescued by the Bangladeshi Coast Guard.

And yet, for many Rohingya in Milwaukee, this year’s Ramadan, which takes place during the governor’s safer-at-home order, brings its own set of worries.

Sheila Badwan, Lead for the Milwaukee Chapter of Hanan Refugee Relief Group and one of their national board members said “they’re already experiencing PTSD just with what they’ve been through, and then to go through this pandemic. I had one family ask me, ‘Are we going to be okay?’” Badwan said she tries to reassure them that “someone cares. We’re still here. We’re not leaving you.”

Zaitun Kamal, 28, a single mother of three living on Milwaukee’s Southside, has been here for almost seven years and works part-time as an interpreter. She was born in Malaysia to Burmese-Rohingya parents. Paying for housing, energy, and wi fi (now a critical resource) and making car payments is currently a struggle for Kamal and many others.

Kamal came to the U.S., she said, because in Malaysia, where many Rohingya refugees live, the government deprived her community of full citizenship rights, including the right to an education. Her children, who are 12, 8, and 5, attend public school in Milwaukee. “Several weeks ago,” Kamal said, her children “receive a computer from school” and are now able to keep up with their studies at home.

Kamal said she and her children “have support from government,” as well as the Rohingya community and the broader Muslim community. But “not being able to get out and be with the community is really hard.”

During last year’s Ramadan, Kamal and her children were able to attend iftar (breaking the fast during Ramadan) at the Rohingya American Society Center located at 16th and Oklahoma. But the Center, which is a hub of Rohingya life in Milwaukee, is now closed for the duration.

Shawkat Ali, founder and executive director of the Rohingya American Society, which operates the Center, said, “the current situation it is very difficult for our community. Mostly they are at home. In case of necessity, they leave for shopping or an appointment.” While some factories, where many Rohingya are employed doing light-industrial work, are still operating, “some people who are working, their hours are reduced,” Ali said.

Kamal said her children too are a “little bit sad because they’re not able to meet with their friends, and they miss their teachers.”

As the head of her household, Kamal observes Ramadan with her two older children, who are fasting. She cooks suhoor (the morning meal during Ramadan) for her children every day. “I usually do some sweet and some spicy food, fried rice, noodles, chocolate milk. They need some sweet . . . Then we pray together and fall back asleep.” For iftar, she makes the chicken and rice dish naisiayam.

Mohamed Anuwar, founder of the organization Burmese Rohingya Community of Wisconsin, said that normally, “when the time comes to open the fast (iftar), we go and gather in the mosque during the evening time, and then we open the fast together. That is the happiest time of the day,” during Ramadan. Anuwar, who attends ISM at 13th and Layton, said “Taraweeh,” which means “rest and relaxation,” is a special prayer specific to the month of Ramadan.

Hanan’s Sheila Badwan said her group has been providing iftar meals to single mothers and single men who don’t have food. “It’s a rough time right now for a lot of families, especially those who were struggling before the corona virus.”

Chef Ramzi Musa contacted Hanan and has been “making family platters” to distribute on Tuesdays and Thursdays, Badwan said. Musa is the sous chef at the award-winning Altitude Restaurant and Lounge in the Crowne Plaza hotel near the Milwaukee airport.

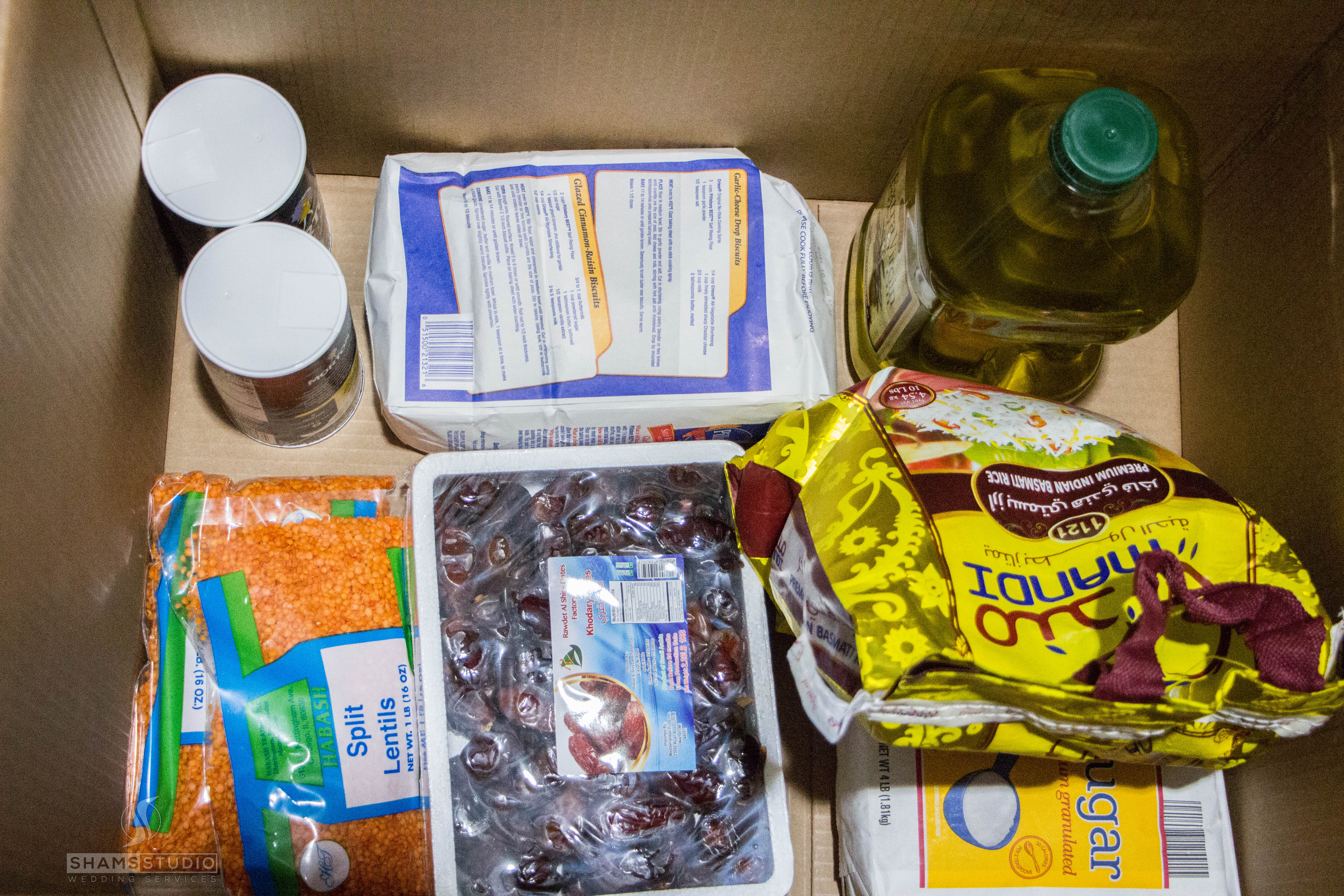

And Marwan Otallah, owner of Milwaukee’s Classic Pizza, has been donating chicken, rice, and potatoes every Friday, distributed in boxes to the Rohingya and others in need. Last weekend, Hanan partnered with ISM to distribute food boxes to refugee families.

“We’ve had so many calls, people saying ‘How can we help?’” Badwan said. When I spoke with Badwan on Thursday, she was on her way to distribute food on Milwaukee’s North Side to Congolese refugees and Burmese Karen, a Christian group. “Some of these families on the North side, when they open the door, you can see a smile on their faces,” she said, despite the dire poverty they are living in.

Ideally, the relief workers, who are careful to protect themselves and practice social distancing, are the only outsiders these families will see.

“I’m hoping the corona virus doesn’t hit the refugee community,” Badwan said, adding that lack of “proper precautions” is the “biggest worry” for herself and the network of people working to support the refugee community during the Covid-19 crisis. She and others are “trying to educate” those who may “already lack on the health-education side” and who are trying to ease their loneliness and anxiety with a little company, even if it’s only close family.

Badwan and the other relief workers are communicating the same message. “We are not supposed to be congregating,” she said. The relief workers remind the refugees, we are all in this together and we will get through it.