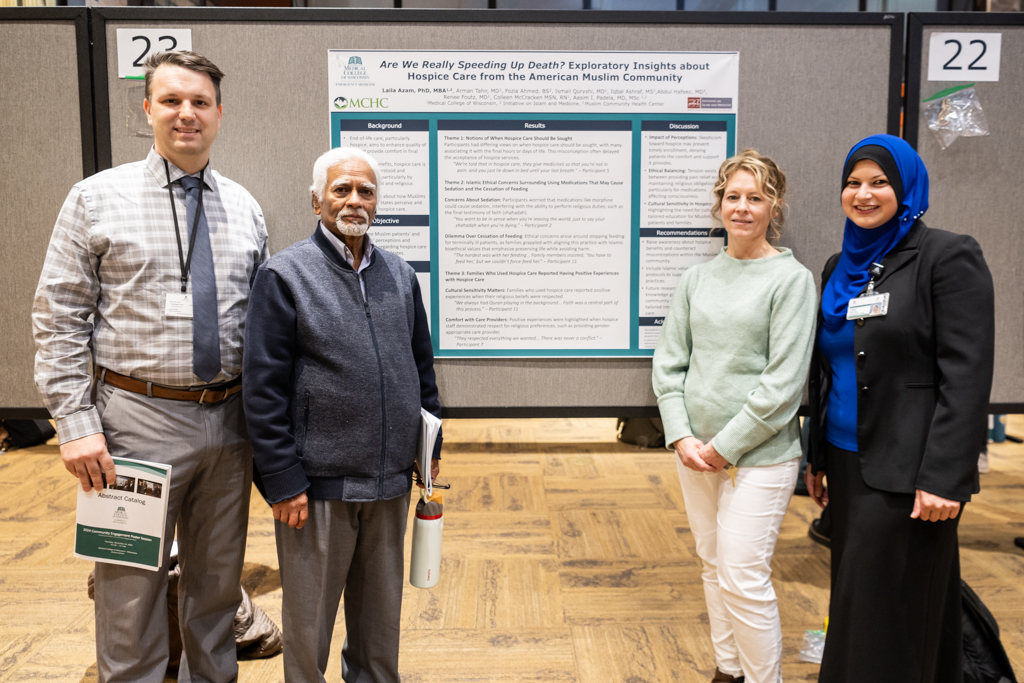

Photos by Mouna Rashid

David Zimmerman of CSTI, Iqbal Ashraf of MCHC and Renee Foutz, M.D., and Laila Azam, Ph.D., of MCW stand by a poster presentation of research on Muslim Americans’ perceptions of hospice care at MCW’s 10th Annual Community Engagement Poster Session.

Few Muslim Americans use hospice care, despite its posited benefits. A multi-sectoral team of academicians and community leaders in southeastern Wisconsin decided to find out why.

The diverse team, including Laila Azam, Ph.D., Renee Foutz, M.D., and Aasim I. Padela, M.D., of the Medical College of Wisconsin; Fozia Ahmed, B.S., Abdul Hafeez, M.D., and Arman Tahir, M.D., of Muslim Community Health Center; and Ismail Quryshi, M.D., of Froedtert Hospital, launched the project, Investigating American Muslim Palliative and Hospice Care Needs, in 2022.

The team’s latest research findings, “Are We Really Speeding Up Death?” Insights About Hospice Care from the American Muslim Community,* presented Nov. 14 at the Medical College of Wisconsin’s 10th Annual Community Engagement Poster Session, used qualitative interviews to explore Milwaukee-area Muslim patients’ and caregivers’ perceptions about and experiences of hospice care in the United States.

Photo courtesy of MCW

Aasim I. Padela, M.D., Medical College of Wisconsin professor/ Vice Chair of Research for Emergency Medicine

Of the 65 research presentations at the MCW’s Community Engagement poster session, this “is the only one that explores an issue that directly impacts this (Muslim) community,” said David Zimmerman, senior project manager of MCW’s Clinical & Translational Science Institute. The CTSI provided funding to support this multi-sectoral “ensemble” team’s ongoing research into unmet medical needs.

The MCW Community Engagement Poster Session highlighted 65 projects presented by students, staff, and faculty from MCW-Milwaukee’s School of Medicine, School of Pharmacy, Graduate School and regional campuses MCW-Central Wisconsin and MCW-Green Bay, with author representation from several different community-based organizations and academic and medical centers.

“Dr. Padela identified this project because he saw in his own research little use of hospice care within the Muslim community,” Zimmerman said. An MCW professor and vice chair of research for Emergency Medicine, Padela, M.D., is a ScholarGPS highly ranked scholar. His prolific publication record and high impact work places him in the top .05% of scholars studying Muslim health worldwide.

“The goal of the ensemble projects is to include all stakeholders and get ideas from the community,” Zimmerman explained. This team was very successful in getting direct input from the community thanks to the Muslim Community Health Center, which facilitated a direct connection with its clients, he said.

More than a knowledge gap

Muslims are one of the fastest-growing religious communities in the United States, numbering between 3 to 5 million, with projections it will double by 2050. “With an aging Muslim population, there is a growing need for specialized healthcare services like hospice and palliative care,” the team’s research explains.

Hospice care “focuses on alleviating pain, managing symptoms and enhancing the quality of life for individuals with life-limiting illnesses nearing the end of life. However, utilization remains low within the U.S. Muslim community,” said MCW researcher and educator Laila Azam, Ph.D. “Like some other groups, Muslim Americans hold some misconceptions about what hospice care is.”

Laila Azam, Ph.D., Medical College of Wisconsin researcher and educator

“Misconceptions are a problem to some extent but it might also be that the current modality of hospice and palliative care does not meet the needs of Muslim communities,” Dr. Padela said. “The package of services that is out there is not actually relevant to Muslim culture, values or beliefs. There is both a knowledge gap and a cultural accommodation gap.

“For example, the ethical issues around withdrawing certain life-sustaining measures, such as the stopping of feeding, are prominently problematic from a religious perspective. Should families not provide feeding tubes and not provide hydration when their loved one is dying? That’s a moral quandary.

“Other issues revolve around the sort of pain medication used. Many hospices automatically put people on morphine drips to prevent suffering. But a morphine drip might also have a sedative that conflicts with the value of being present when you’re dying. If you are not adapting a protocol for Muslim patients, that’s a problem.

“That’s aside from a whole host of issues around being Muslim in a medical setting. Do you have the right type of halal food? Do you have gender concordant care? Do you have the ability for someone to help the patient wash themselves when they want to pray? Hospital systems aren’t necessarily set up to accommodate all these extra needs.”

Through a qualitative descriptive study with a Muslim patient and 10 family caregivers, the research team identified their perceptions of hospice care, ethical concerns and experiences. Among their varied perceptions, many saw it as useful only in the last hours of life. Participants also had ethical concerns about the use of sedative medication and with cessation of feeding terminally ill patients. Some had concerns about how hospice care might lead to unnecessary interventions or even hasten death.

Photo by Mouna Rashid

Ishma Rizvi (center) and Duaa Majeed (right) of Muslim Community Health Center speak with Laila Azam, Ph.D., and Renee Foutz, M.D. Rizvi is assisting with the creation of the resource guide.

However, some reported positive experiences when hospice services respected religious beliefs, including supporting opportunities for reading or listening to the Qur’an and respecting prayer times.

Putting research into practice

The research team concluded that both misconceptions and ethical concerns about hospice may deter American Muslims from seeking and benefitting from hospice care. They propose addressing both Muslim’s understanding of hospice and the integration of Islamic culture and religious values into hospice care.

It is not just a matter of explaining hospice to Muslims and they will come, Dr. Padela said.

Fostering informed decision-making can enhance patient satisfaction and improve overall care outcomes, the research notes. The team is developing an informational resource, Islamic Bioethical Considerations for the End of Life: A Guide for Muslim Americans, to help Muslims who struggle when thinking about death and dying.

Photo by Mouna Rashid

This is a good step, Padela said. “The mega-project would be to develop a Muslim art of dying, a workbook for Muslims to help them engage deeply with the questions of dying in a medicalized way in the United States or elsewhere.

“It would include the sort of questions you have to think about, what you have to talk with your family about, what the Prophetic sayings, the tradition, say about dying, how the Prophet prepared himself—something we should all address before we have these moments of crisis.

“Still, that’s an interval step towards what would really be desired—to create a Muslim healthcare system that is rooted in our religious beliefs and values, but also addressing the needs we all face at the end of life.”

*This project was supported by the CTSI Team Science-Guided Integrated Clinical and Research Ensemble, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, Award Number 2UL1 TR001436. The content is solely the responsibility of the author(s) and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.