It’s a crisp, sunny Saturday in early March, and customers are lined up outside the Milwaukee Public Market, masked and waiting for their turns to patronize one of its many restaurants and retail shops.

It’s a welcome sight for Azmi Alaeddin, whose flagship Aladdin’s eatery has drawn customers to the market in Milwaukee’s trendy Third Ward for years.

Like many restaurateurs, Alaeddin has struggled to stay afloat in the global COVID-19 pandemic. But the near-spring thaw and optimism over the vaccine rollout have lured more and more patrons from their homes in recent weeks. And Alaeddin and other Muslim restaurateurs in the Milwaukee area are hopeful that the trend will continue.

“I can feel it. It’s coming back,” said Alaeddin, who also operates two satellite locations downtown, inside Milwaukee’s City Hall and the Intermodal Amtrak Station.

“People are eager to go out. They miss seeing each other,” he said. “If I wanted to forecast, I’d say business is going to be very strong when it comes back.”

The pandemic, which has killed more than 500,000 people in the United States alone, has decimated many businesses, including restaurants. And the Milwaukee-area’s Muslim-owned eateries were not immune.

Many saw their sales plummet, in some cases more than 50%. Some had to cut staff and hours. They pivoted to or amped up their carry-out options, partnered with delivery services, added menu items — anything they could to bolster sales. And those that qualified, took advantage of the business relief packages made available by local, state, and federal agencies.

While some restaurateurs say they are bouncing back, some businesses did not survive, and others are barely hanging on.

“Every restaurant had a different experience, depending on your location, what kind of service you had,” said Alaeddin, who — with three downtown sites — was especially hit hard by the exodus of office workers and the cancellation of festivals and other events that traditionally bring people into the city.

“If you were in a neighborhood and had online ordering, maybe you did great, you had an increase in sales. But if you had a sit-down restaurant, you saw a total decrease in your business — a big loss.”

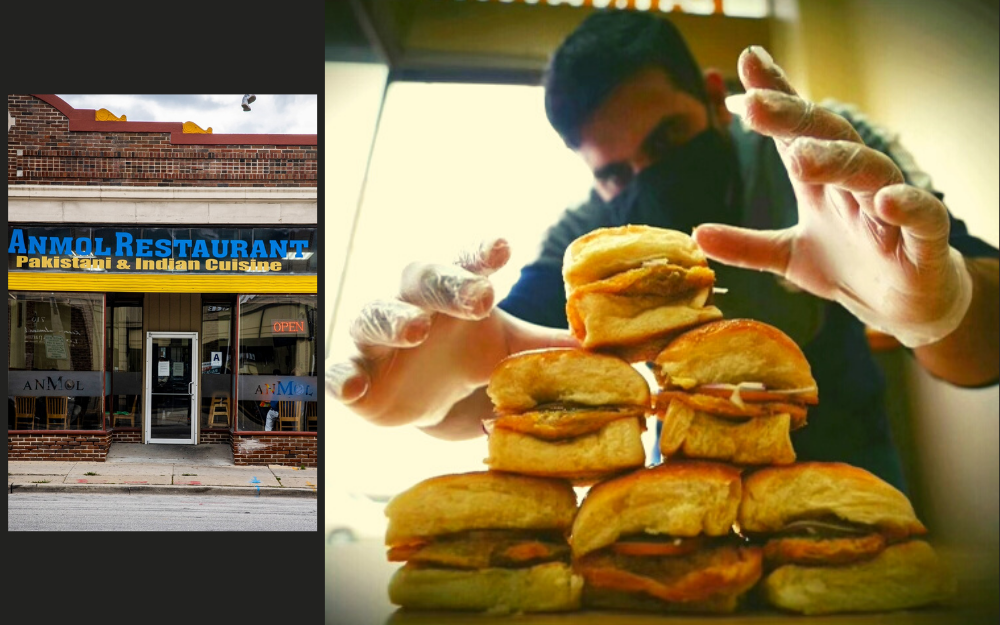

That was true for Taqwa’s Bakery and Restaurant in Greenfield and Anmol on Milwaukee’s south side, both of which saw sales drop over the winter months with skittish diners reluctant to eat indoors.

It was a tough blow for Taqwa Obaid and husband Abdullah Habahbeh, who opened the eatery in July in the midst of the pandemic after two years of planning and remodeling what had been a former Burger King restaurant. They’d considered delaying the launch, but it was too late to turn back.

The first two months were busy as curious customers checked out the new eatery where outdoor dining was an option. But things slowed as the winter wore on. They kept a core following of loyal customers, many returning for their signature taboun bread and healthy breakfast options. Still, it was not enough to offset the mostly empty dining room.

The couple had to trim some staff hours. Obaid, a much-sought-after caterer before opening the business, began knocking on doors of nearby doctors’ offices to promote her catering options. But they were not eligible for any business assistance because they had opened during the pandemic.

“In the last two months, it was really tough,” said Obaid, whose husband may now look for an outside job to help pay the bills.

“I’m hoping by June it will pick up because we’ll have the outside seating open then,” she said.

Taqwa bakery owners fighting with the covid.

At Anmol, owner Arif Patel said he is already seeing strong signs of a recovery with sales in the last week nearly doubling their pandemic levels and a spike in calls for catering, which had slowed to a trickle over the winter.

“This summer is looking very promising,” said Patel, who also operates two Illinois sites, in Chicago and Naperville. “I think we’re probably going to be busier than ever before.”

At the height of the pandemic, Patel said, sales dropped about 50% overall, driven by an even steeper dive in catering.

Customers flocked to the takeout option, some ordering two or three times a week just to patronize the business, he said. He invested in online marketing and began shipping frozen foods, initially to accommodate Illinois customers after those restaurants were forced to closed.

“Within two weeks, we got an e-commerce site built. And when the orders come in, we can ship them out so the customer never has to leave their house,” he said.

Patel was forced to close the Milwaukee site for about 10 days after some employees contracted COVID. He used the downtime to remodel the dining room. He said he had to cut staff from about 25 to 12, raise catering prices because of the fluctuating prices of wholesale foods. And he changed the dining room model to have customers order at the counter.

The staffing cut really hurt, he said.

“Now, we’re short-staffed with the events coming in. It’s always been like a see-saw. It’s really hard to get that balance right.”

Anmol owner Arif Patel tries to get a perfect shot of his Bun kababs (vegetable burgers) for the restaurant’s new online frozen food shop.

Mahmoud Saed, who owns two Shawarma House restaurants in Brookfield and on Milwaukee’s east side, did not have to lay off workers or cut hours. Nor did Marwan Otallah, who actually added drivers at his south-side Milwaukee Classic Pizza in response to the spike in delivery orders.

“We started putting money into online advertising. We wanted to show people that we were delivering from Day One,” said Saed, who opened his first location in Milwaukee in 2014.

Saed also tweaked his menu, adding a Greek gyro and other items including a shawarma meat burger that he said has been a big hit on social media.

“We had to pivot. We were trying to collect customers everywhere, not just Middle Eastern,” said Saed, whose eateries grew out of his MBA project at Cardinal Stritch University. “We were just trying to keep the ball rolling. And it worked. Now we’re doing really good.”

Milwaukee Classic Pizza saw a spike in sales when other nearby restaurants closed, and with a small staff, he was able to keep everyone employed.

“We were one of the lucky ones,” he said.

Others did not fare so well. Anas Toukam, who opened Rimass Kitchen in Kenosha as its majority partner in July 2019, closed its doors in late 2020. Sales had plummeted as nearby businesses were shuttered; wholesale prices of some of his food items soared, and overhead costs were mounting. And he was forced to cut his losses.

It was a devastating blow for Toukam, a father of four, who had moved his family from Morocco for the venture. He is regrouping, working for another restaurant for now. But he hopes to strike out on his own again, once the pandemic has passed.

“Before corona, it was good,” said Toukam, who was not eligible for the relief packages. “Before Corona, it was coming up, every month it was better.”

Shawarma House

Owners whose businesses have survived this long are beginning to see signs of a comeback. But there’s no consensus about when and whether things will truly return to normal.

Sales at Aladdin’s Public Market site are still at about 50% to 60% of where they were pre-pandemic, according to Alaeddin. And they’re much lower at his other two locations. Alaeddin survived, he said, in part because he had built savings, had no business loans and was able to tap into the relief packages.

“But some people had no choice,” said Alaeddin, who had to change his point-of-sale system to accept online orders and partnered with food delivery businesses though it cut further into his sales. “If you have a rent and employees and a mortgage, there may be no way to survive.”

Alaeddin is hoping to see a return to 70% to 80% of his pre-pandemic sales by June or July. Saed, of Shawarma House, thinks a full recovery could be a year out. But between the recent tweaks to the business and the eventual rebound in catering and events, he thinks sales could be better than ever.

Otallah is bullish enough on the recovery that he has launched a second restaurant just down the street from his pizza place. Otallah opened Gordo Burger in a newly vacant site in Milwaukee’s Bay View neighborhood in January, in part to counter the negative perception of having a vacant storefront on the street. But he’s also confident that restaurateurs still standing will rebound.

“We’re optimistic. The slope is on its way down, and hopefully, everyone will get vaccinated,” said Otallah, who is seeing more patrons out and about with the warmer weather. “Let’s start a new chapter in 2021. It can’t be worse than 2020.”

Gordo Burger

If there is a universal experience among the restaurateurs interviewed it was a sense of gratitude for their most loyal customers, some of whom purchased more items and ordered more often to help keep their businesses alive.

At Aladdin’s, where tipping tended to be minimal because it was counter-service rather than sit down, customers encouraged Alaeddin to add electronic tipping and generously filled the jar on his counter. One customer, he said, threw in a $50 bill, saying, “that’s for your guys.” Another gave $100 to an employee after they were closed for six weeks, saying, “I know you’ve been off for a while. This is for you.”

“Sometimes, you see that customer, and you know the only reason they’re here, or they’re buying a little extra, is just to help you. You can see it in their eyes. It’s such a beautiful thing,” said Alaeddin.

“It’s amazing the goodness that comes from people in tough times.”