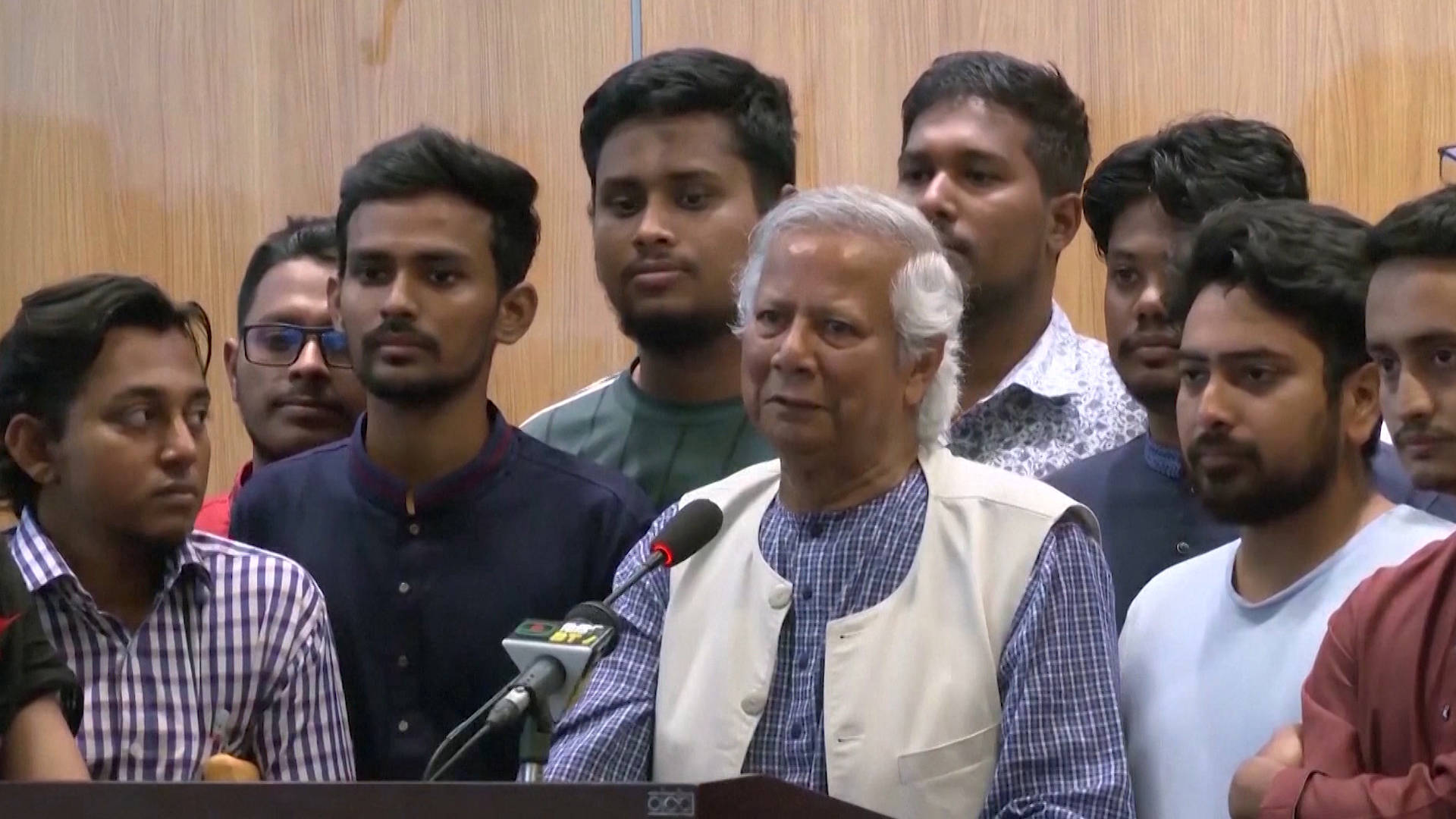

We go to Dhaka for an update as Nobel Peace Prize laureate Muhammad Yunus is sworn in to lead Bangladesh’s caretaker government just days after the ouster of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, who resigned and fled the country amid a wave of student-led protests over inequality and corruption. Yunus is known as the “banker to the poor” and was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006 for his work developing microloans that helped lift millions out of poverty. Yunus thanked Bangladeshi youth for giving the country a “rebirth” and vowed to work for the public good.

“This is uncharted territory,” says Shahidul Alam, an acclaimed Bangladeshi photojournalist, author and social activist, who has spent decades documenting human rights abuses and political and social movements in the country. Alam was jailed in 2018 for his criticism of the government and spent 107 behind bars, during which time he says he was tortured by the authorities. “This repression has taken such a toll on so many people for so long, the nation is just hugely relieved.”

We also speak with Nusrat Chowdhury, an associate professor of anthropology at Amherst College and author of Paradoxes of the Popular: Crowd Politics in Bangladesh. She says it’s very significant that student leaders are being brought into the new government and says Yunus is a rare public figure in Bangladesh who exists “beyond party politics” and has the chance to unify the country.

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: Nobel Peace laureate Muhammad Yunus has been sworn in as head of Bangladesh’s caretaker government just days after the ouster of Bangladeshi Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina following weeks of student-led protests. Yunus, a longtime critic of Hasina, took the oath during a ceremony at the presidential palace in the capital Dhaka Thursday. Over a dozen other members of Yunus’s Cabinet were also sworn in, including two students who led the mobilizations forcing Hasina’s resignation: Nahid Islam and Asif Mahmud. Adilur Rahman Khan, a prominent Bangladeshi human rights advocate who documented extrajudicial killings, forced disappearances and police brutality and was sentenced to two years in prison by Hasina’s government, will also be an adviser to Yunus’s interim government while Bangladesh prepares for new elections.

Muhammad Yunus is known as the “banker to the poor.” He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006 for his work developing microloans. On Thursday, Yunus spoke after landing in Dhaka and shared a message for Bangladesh’s youth and students.

MUHAMMAD YUNUS: [translated] Using the means of revolution, Bangladesh will create its new dawn of victory. Keeping this vision ahead of us, we have to keep going ahead. I want to express my gratitude and praise the youths who have made this possible. They have protected this country and given it a rebirth. And we wish for this new Bangladesh to progress with speed. We have to protect this freedom — not just protect it, we have to ensure that it reaches every single household; otherwise, the freedom will have no meaning.

AMY GOODMAN: For more, we’re joined by two guests. But we begin in Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, with Shahidul Alam, an acclaimed Bangladeshi photojournalist, author and social activist, who has documented human rights abuses, political and social movements.

We welcome you to Democracy Now! In 2018, Bangladeshi police arrested Alam from his home over comments he made during an interview with Al Jazeera critical of the government’s violent response to nationwide student-led protests at the time. Alam was imprisoned for 107 days and reported being tortured by authorities. He was released following a global campaign by humanitarian groups, media and journalists. In 2018, Alam was included in a group of journalists called “the guardians” that Time magazine recognized as the Person of the Year. On the eve of Thursday’s swearing-in, Alam shared a photo of Muhammad Yunus on X from when they met before the Nobel Peace Prize.

Shahidul Alam, welcome to Democracy Now! It’s great to have you with us. Can you talk about the significance of this moment and what brought Bangladesh to this point where Muhammad Yunus, the man you photographed many years ago, is now the head of the caretaker government?

SHAHIDUL ALAM: It’s a phenomenal event. I mean, I’ve been through 1971, our war of liberation. And being in the streets on the 5th with people jubilating was a greater thrill than that time, which is difficult to imagine.

But it is a difficult process. I mean, this is uncharted territory, the fact that the government is suddenly gone. And there was the few days in between when there wasn’t a government. And that potentially, and did, to an extent, lead to local violences. But that’s been curbed, and we look forward to a new dawn ahead. I mean, this repression has taken such a toll on so many people for so long, the nation is just hugely relieved.

AMY GOODMAN: Tell us what happened, what led to the student-led uprising, and why it was the students that took down the Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, who has now fled to India.

SHAHIDUL ALAM: It was a people’s movement, but triggered by the students. And their initial protest was about an unfair policy regarding government job allocations. And that, I feel, could have been handled, could have been handled well. But it was the arrogance of the tyrant that led to it. They wanted to meet the president. He didn’t respond. She, in an interview, sneered at them, calling them Razakars, which is a swear word here, because it talks about — it’s about collaborators of the Pakistani Army, so, essentially, something going against our war of liberation, our freedom movement.

And the students were enraged. Initially, one of the demands was that she apologize. But this prime minister, or the prime minister we had, is not the apologizing type. Instead, she turned her armed goons on them. They killed six people. When they wanted to bury these people, have a funeral, including there was one young man, Abu Sayed, who had been shot at point blank by the police in a video that went viral, they instead turned really aggressive, and the police started killing. And eventually, it just became a killing spree. So, that lit the fuse completely, and then I don’t think there was any going back.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about your own experience, Shahidul Alam, being arrested under Sheikh Hasina’s government? What happened back in 2018?

SHAHIDUL ALAM: I wasn’t arrested; I was picked up. Ironically, it was on the very day, the 5th of August, 2018, when they picked me up, that — and six years later, on the 5th of August, she fled. So there’s an irony there.

But yeah, again, it was a student protest. I had been documenting it. On the 4th of August, again, the armed goons, associated with the government, attacked me, attacked my equipment. I was back in the streets on the 5th. That day, I gave an interview to Al Jazeera. That night, sitting here in this flat, I was uploading material when the doorbell rang. I went to answer it, and suddenly these burly people came in. They dragged me away, handcuffed me, blindfolded me, put me in this microbus and took me away. Now, I live in Bangladesh. I know what happens. So what I did was resist and scream as much as I could, so I didn’t go away silently. That is one of the things that does happen in Bangladesh, disappearances, and then people just don’t appear again.

But that night, I was tortured. The following day, they offered me a deal, saying if I agreed to stay quiet, I would be let go and there would be nothing on record. When I turned that down, they got very angry. I was taken to jail — to court. In court, I mentioned that I had been tortured. And the court is required to investigate that. They did not and put me into remand, which is a sort of euphemism in Bangladesh for state-sponsored torture. I was there for six days, then I went to jail. My bail attempts, five bail attempts, were refused. On the sixth, there was just so much pressure from people in Bangladesh and across the globe that they eventually let me go.

But even now, today, six years after the event, the trial has not begun. The charge has not been placed. The law I was picked up under has been repealed. Yet I appear in court every month. I am next due to appear on the 14th of August.

AMY GOODMAN: And have you spoken with Sheikh Hasina since then, the prime minister? And talk about her role in history, her father and Sheikh Hasina herself.

SHAHIDUL ALAM: Well, her father led the movement. He was a principal architect of the movement towards liberation, and he was very revered, initially. And then things went wrong. He began to get autocratic himself. He set up a private militia, called Rakkhi Bahini. He disbanded all political parties and created a single-party state. Except for four newspapers which were pro-government, all other newspapers were banned. And there was huge repression at that time. That was the first of the extrajudicial killings that we’ve had. He was assassinated on the 15th of August, 1975.

And August is meant to be the month of mourning, officially called by the government, because his daughter, until recently, had been the prime minister. But the protesters have turned it around. I mean, July was when I was documenting — or, at least the student protests began six years ago. Again, July was when the quota movement began this time, and they’ve called it the red month. And instead of counting the days of August, they’ve extended July, and it’s now a month of red. So that month of mourning has been turned into a month of revolution.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to go to a clip of Muhammad Yunus, who first joined Democracy Now! in 2008, not long after he won the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize for pioneering a microloan program that helped hundreds of thousands of impoverished Bangladeshis, mainly women. We also spoke to him in 2017 about his book A World of Three Zeros: The New Economics of Zero Poverty, Zero Unemployment, and Zero Net Carbon Emissions. The book came out the same time as an Oxfam report which found the eight richest men in the world own more wealth than half the world’s population, more than three-and-a-half billion people. I asked Muhammad Yunus to talk about zero net carbon emissions and zero poverty.

MUHAMMAD YUNUS: But the system which we have been practicing, the capitalist system — I said capitalist system is not working towards it. It’s a system which, as you mentioned, eight people owning more wealth than the bottom 50% of the people. It’s a system which is like a machine which is sucking up wealth from the bottom and transporting it to the top. So the top is becoming a big mushroom of wealth. And then, 99% of the people is like the stem from the mushroom hanging there. And that stem is becoming thinner and thinner. The portion of the wealth devoted to bottom 99 — or, the 99% — we don’t say “bottom” anymore — becoming smaller and, regrettably, the top becoming bigger and bigger.

So this is a ticking time bomb. Anytime it can explode — politically, socially, economically and so on. We are not paying attention to it. Wealth concentration was going on ever since we introduced capitalist system, but this was not very visible. Today, it’s becoming worse and worse. The speed of wealth concentration has become speedier and speedier. Years back, there was — a couple of years back, it was 32 people who owned half, the wealth of the bottom 50%, and now we have eight. Soon we will have five. Soon we will have two, two people owning the whole entire world’s wealth together. So those are the kind of things threatening.

When concentration of wealth takes place, it’s also the concentration of power. Wealth and power go together. So you control the government, you control the politics, you control the media, you control businesses, everything. So that’s the kind of situation coming. And all the people at the bottom, bottom 10%, 20%, 50%, they will have tremendous anger against the way that’s being done and how to express themselves that will create the destability in the society.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Muhammad Yunus taking on capitalism on Democracy Now! in 2017, now just sworn in as the interim head of Bangladesh after a student-led uprising. In addition to Shahidul Alam, we’re joined by Nusrat Chowdhury, associate professor of anthropology at Amherst College, author of Paradoxes of the Popular: Crowd Politics in Bangladesh.

Professor, you grew up in Bangladesh. You’re speaking to us, though, from Northampton, Massachusetts. If you can comment on what Muhammad Yunus was saying then, presumably what he believes today, and what that could mean for the future not only of Bangladesh, but, as a world leader, for the world?

NUSRAT CHOWDHURY: Thank you.

I think one of the things that made Yunus come back and take on this position is the fact that the students really wanted him as the head of the interim government. And one of the reasons for that is that most people in Bangladesh are wary and weary of party politics. So, one of the reasons why these particular student protests — and the ones that have been successful in the past — succeeded, albeit at a very steep cost, is because it didn’t start with any particular political party affiliation. The students were very clear from the beginning. They said that if you are a student, you can join us, but don’t come here as a representative of any political party.

And in a place like Bangladesh, it’s difficult to find people who have kind of wide acceptance, who enjoy wide acceptance and recognition from all walks of life — from people of all walks of life. And Muhammad Yunus still enjoys that recognition. He also has — he’s globally recognized. He has international legitimacy. So, he is one of those people.

I am not sure how much his economic vision actually plays a role in this or will play a role in this. Muhammad Yunus, as you know, in his earlier work, had talked about social capitalism. His own position has changed. I’m not an economist. I’m not going to dwell on that. But I think at this point it’s what he represents. Having — enjoying a kind of recognition beyond party politics is what makes him an ideal candidate for the interim government.

AMY GOODMAN: And, Professor Chowdhury, the significance of not only the student-led uprising, but now in Muhammad Yunus’s government, they have included two students?

NUSRAT CHOWDHURY: Yes, that is unprecedented in the history of Bangladesh, although almost all of the successful political movements in independent Bangladesh have been led by students. And, of course, then ordinary citizens joined them. So it’s not surprising that the students led this protest, but their inclusion is unprecedented.

But it also symbolizes the fact that you cannot ignore students as the youth, as young, as, you know, not really having the skills to understand what’s going on politically, because I think it would be a grave mistake right now for anybody, including the military in Bangladesh, to disregard what the students were saying, because they were able to accomplish something that even the veteran political parties haven’t been able to in the last 15 years. They had widespread support from ordinary citizens of Bangladesh. So, I think it’s great that the students are included. It’s also strategic. I don’t think you can actually have any kind of policies right now without consulting with the students, who have shown so much maturity and efficiency in actually bringing this uprising about.

AMY GOODMAN: And being very clear, even as Sheikh Hasina fled to India and the military said they would, you know, caretake the government until there was an election, they said no to the military even temporarily, Professor.

NUSRAT CHOWDHURY: Yes, absolutely. There is very little faith. Again, the military is broadly seen as nonpartisan, despite its internal factions. But there is a history in this part of the world of military coups. So, the students have been very clear from the very beginning that they don’t want an interim government led by the military. And the military right now would make a big mistake if their own political ambitions come in the way. So, yes, they have been very clear about having a civilian-led government.

AMY GOODMAN: So, Shahidul Alam in Dhaka, what’s going to happen next? You’ve got this caretaker government headed by the man who pioneered microloans not only in Bangladesh but around the world, Muhammad Yunus. How long does this caretaker government go on? And will there be a role for someone like Khaleda Zia, who was freed just after the prime minister fled? She was the opposition candidate.

SHAHIDUL ALAM: Well, Khaleda has been freed, but one of the things that the students also talked about was that they did not want dynasty politics. Khaleda Zia is the widow of General Ziaur, who was a former president. Sheikh Hasina is the daughter of Sheikh Mujib, who was the founding president. But these families have gone on, and the parties themselves have not been democratic. I think there is a great cry for some other option right now.

What we have to see first is how this caretaker government manages this situation. This is uncharted waters. Neither professor Yunus nor any of the other people in his Cabinet have dealt with a situation like this. But then, this Cabinet has students. This Cabinet has more women than in any previous cabinet. It has human rights activists. It has Indigenous people, so minorities are also represented. But there are questions. There are questions in terms of the competence of some of the people. There are questions about whether some people are there because they’ve just been yes-men in the past and, you know, nonthreatening. So, those are questions that will exist.

But for me, the hope is that the students have not stopped there. I was walking down the streets today. There has been violence in the streets, because this anger has led to seeking revenge. And the students are managing the streets. The students have gone out in patrols at night to ensure that the robbery and the thuggery does not continue. And the students keep insisting that they want a government which really belongs to the people.

AMY GOODMAN: Finally, Shahidul Alam, on a slightly different issue, we’ve noticed in the streets, as the tens of thousands of students and others protest, that there have been flags of Bangladesh and flags of Palestine. You also have been an outspoken supporter of Palestinian rights. As we move into a segment in the United States on the role that Israel and Palestine will play in this election for the next president of the United States, if you can talk about what’s happening here, there?

SHAHIDUL ALAM: Well, I’ve just put on my keffiyeh, which is what I usually wear. I hadn’t remembered to do it then. But last night at the swearing-in ceremony, I was the only person from civil — well, only nonstudent wearing a keffiyeh. One of the students was also wearing a keffiyeh. And the Palestinian ambassador came and hugged us both.

But, yes, at the time of the protests themselves, I remember a young man atop a tree waving both a Bangladeshi flag and a Palestinian flag. And this is something which is important for a different reason, as well. While Bangladesh officially recognizes, you know, talks about Palestine and its liberation, it has actually been trading with Israel. It’s used Pegasus and other surveillance material. It’s had training with Israel, and it has much more connections in terms of its military and its training than it likes to reveal. And the Bangladeshi public — the Bangladeshi Constitution, in fact, says that it will be with all oppressed people across the globe. So, it’s a natural affinity, but the Bangladeshi people in particular do have a resonance with the Palestinian movement. And I think the students being there will ensure that once we’ve sorted out the internal things, we will be looking after Palestinian issues.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, Shahidul Alam, we want to thank you so much for being with us, Bangladeshi photojournalist and activist. He was detained by the Bangladeshi authorities back in 2018, and he was held for more than a hundred days, leading photojournalist in Bangladesh. And Nusrat Chowdhury, we want to thank you for being with us, professor of anthropology at Amherst College, author of Paradoxes of the Popular: Crowd Politics in Bangladesh