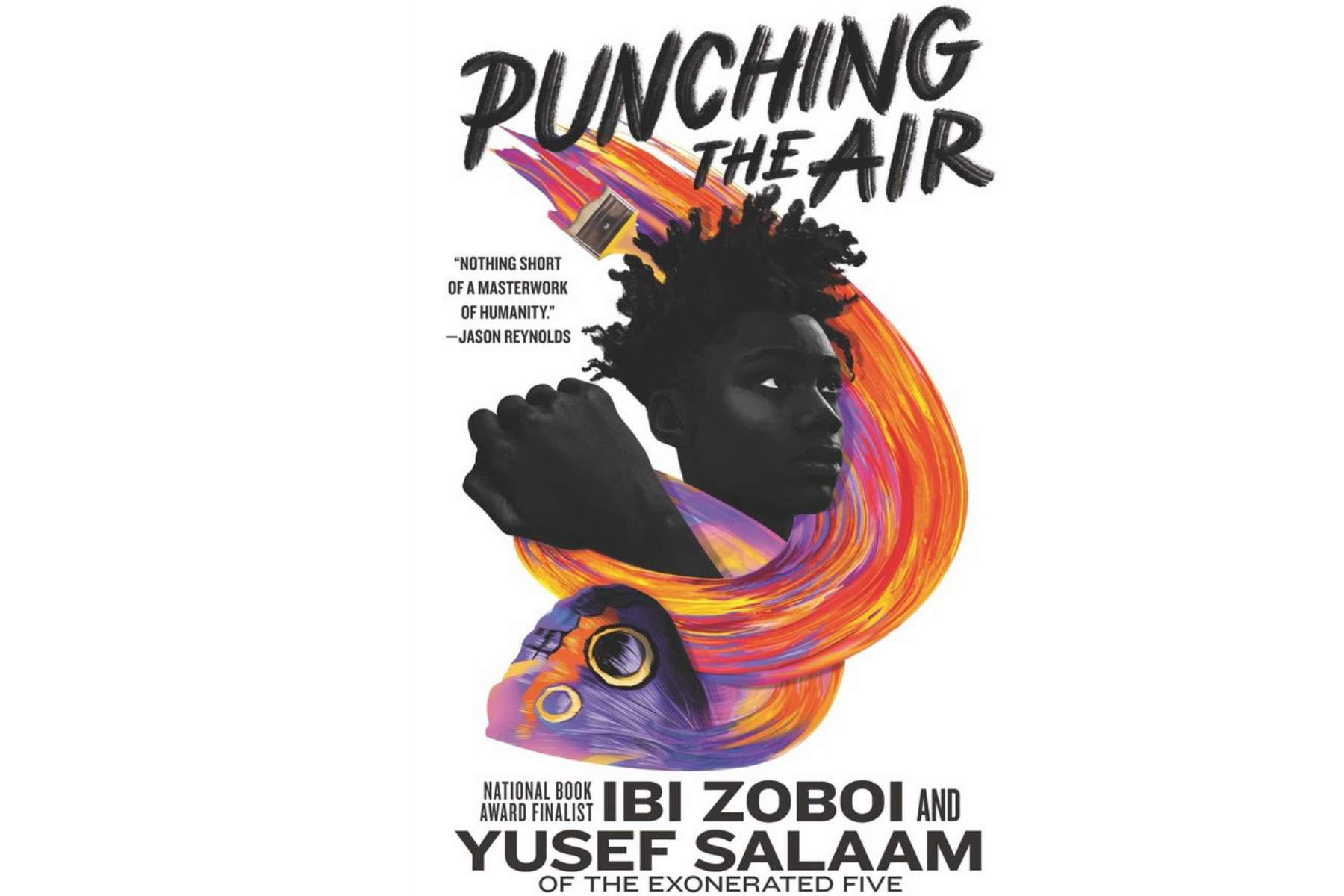

Punching the Air is a novel in verse about a 16-year-old boy, Amal, with a budding artistic talent and promising future, who is put away in prison for throwing a punch. But in a way, was he put away before that, by an uncaring and prejudiced system?

Yusef Salaam, who has become a noted educator and activist after spending more than six years in prison for his wrongful conviction in what was known as the Central Park jogger case, wrote the book with author Ibi Zoboi.

“I write books for children, and I wanted the world to remember that Yusef was a child when this happened to him and I was a child as well,” Zoboi says. “When I remember this case, and those boys look like the boys in my classroom, the character had to be inspired by Yusef and this story had to instill a sense of hope in the reader. So we came up with a name, and that name is Amal. And Amal means hope in Arabic.”

Interview Highlights

Salaam on how prison felt

Once you accept defeat, you then become your own worst enemy. You begin to internalize, and then therefore live out, a life devoid of purpose, a life as a mistake. But you are born on purpose and you have to remember that. And that gives you tremendous hope in being able to overcome anything.

Had I given up hope, had I given up everything, my humanity, I would have turned into what they wanted me to turn into.

Yusef Salam

You always have moments of doubt, and just before you give up hope, things happen in your life that jar you back awake to the reality of what purpose is all about. You look up at the sky, even though you’re behind bars, you can still see the beauty in creation. Had I given up hope, had I given up everything, my humanity, I would have turned into what they wanted me to turn into. And I’ll never forget, my mother said when she came to the precinct, she said to me, they need you to participate in whatever it is that they’re trying to do, do not participate, refuse.

Zoboi on working together

Well, as you can hear, Yusef has so much wisdom to bring to his story. When thinking about how to write the story, it wasn’t so much about us coming up with a plot, coming up with the characters together. We decided that we had to make Amal a 2020 version of 1989 Yusef, and that is a boy who is incredibly self-aware. He was aware of just a history of criminal justice in this country, at 16 while it was happening to him. So in that sense, this was my way of just taking all of Yusef’s world views, his perspective, his hindsight, and putting it in the form of poetry through the eyes and experiences of a 16-year-old fictional character.

Salaam on dealing with anger

That is when I look at mentors, you know, Nelson Mandela said that he had to leave anger and bitterness in the prison, because if he took it out with him, it would turn into something and destroy him. Whereas Dr. Maya Angelou said you should be angry, but you must not be bitter. She said bitterness is like a cancer, it eats upon the host. It doesn’t do anything to the object of his displeasure. And then she gives us a way to become alchemists in our own lives. She tells us to use that anger. You dance it, you march, you vote it, you do everything about it. Then she said, you talk it, never stop talking. And that’s really what this book is about as well. It’s about the artistry. It’s about finding purpose, finding resilience. It’s about falling down in life and getting back up. It is about becoming your best self, even though you are being judged by the color of your skin and not the content of your character.

Dr. Maya Angelou said you should be angry, but you must not be bitter. … And then she gives us a way to become alchemists in our own lives. She tells us to use that anger.

Yusef Salaam

On the Jacob Blake shooting and what’s on their minds now

Salaam: You know, what’s on my mind is, we are not free. We are fighting in a war that we didn’t know we were in. But one of the beautiful things about it is that because of the color of our skin, we are automatically fighting on the side of right, because we are trying to make the best out of what we’ve been given. You know, being shot in the way that Mr. Blake was shot is beyond tragic. And then when you couple that with the fact that his young sons was in the car witnessing this tragedy. It’s a miracle that he is alive today. But what does that say about how the people who are supposed to protect and serve us move in reality? It says that there is two Americas, separate and unequal, divided and disunited.

Zoboi: Well, this was always part of my reality, our reality, in fact, growing up in New York City. And I’m coming at it from an immigrant’s perspective, I was born in Haiti and came to the U.S. at four years old. So in that sense, for many people around the world, being here is the American dream. But once we are here and can start to connect the dots that make up the racial injustices in this country, we realize that it can be a nightmare for some. And while there can be individual successes, — we see it with, you know, the recent vice presidential nominee. And we had Barack Obama as a president. There are individual successes. What do those successes mean when there are constant injustices? So this is something I’m grappling with as a mother, as an author for children’s books, that what does freedom mean when there are still these tragedies taking place year after year after year?

This story was produced for radio by Hiba Ahmad and Ed McNulty, and adapted for the Web by Petra Mayer