Photos by Rawand Yazaw

Atia Abawi, first-ever author-in-residence at University School of Milwaukee, moderates a panel of distinguished guests to speak about the refugee experience. (from left to right) Atia Abawi, Maryam Durani, cultural advisor to the Hanan Refugee Group, Khatera Nazari, student and former refugee, Janan Najeeb, director of Milwaukee Muslim Women’s Coalition and Ben York, refugee coordinator for the State of Wisconsin.

Eight hundred sixty-eight is the precise number of Afghan refugees who have settled in Wisconsin since Kabul fell to the Taliban in August of 2021. More are expected to arrive. Two Afghan women refugees, Maryam Durani and Khatera Nazari, were among the speakers at the “Afghan Refugee Crisis: A Panel Discussion,” held at University School of Milwaukee on January 24.

The panel was moderated by novelist Atia Abawi, the University School of Milwaukee’s (USM) author-in-residence. It was the second in a series of visits to USM this school year by the acclaimed writer, the daughter of Afghan refugees from the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. After serving as the Kabul correspondent for CNN and NBC, she wrote a young adult novel based on her experiences in the country, The Secret Sky: A Novel of Forbidden Love in Afghanistan, followed by a heart-rending novel set during the Syrian civil war, A Land of Permanent Goodbyes. The author-in-residence program, sponsored by a Think Big grant, has allowed Abawi to work with students at all levels on topics such as journalism, international relations, creative writing, news literacy, identity and refugees. She will return for a final session at USM in April.

The Afghan refugee panel also included Janan Najeeb, president of the Milwaukee Muslim Women’s Coalition, and Ben York, refugee coordinator for the State of Wisconsin.

Durani had a distinguished career as an advocate and role model for women before leaving Afghanistan. In 2005, at age 21, she was elected to the provincial council of Kandahar, a dangerous role in a district where Taliban fighters were active. She founded and headed several initiatives for women in the region, including a cultural center and a radio station. She survived suicide bombers and other assassination attempts. In 2012, she received the International Women of Courage Award from Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and First Lady Michelle Obama. In that same year, Time magazine included her in its annual list of the “100 Most Influential People in the World.”

Now Durani is in Milwaukee, working as cultural advisor to the Hanan Refugee Group headquartered on the city’s south side. She is a refugee helping other refugees.

But despite her prominent role, in many respects, the story she told the audience could have been the story of any Afghan refugee. She spoke of the difficult exit at Kabul airport, the crying children and desperation, her gratitude toward the U.S. She laughed when she mentioned that someone warned her upon arrival in America that Milwaukee was “unsafe.” Unsafe is a word better describing the situation of the family she was forced to leave behind.

Maryam Durani, renowned Afghan women’s rights activist and one of TIME magazine’s 100 most influential people now working with Hanan Refugee Relief Group in Milwaukee, WI.

Durani discussed the work of the Hanan Refugee Relief Group, whose scope includes providing newcomers with halal food and organizing group activities including English classes, aiding adults in their job search and helping children and teens “to manage between two cultures.” For the old as well as the young, “it’s not easy to find your way in a new society,” she said. Hanan is here to help.

Khatera Nazari is a young refugee enrolled at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee as a biomedical engineering student. She noted that January 24 is International Education Day—everywhere except in her homeland. “It’s such a horrible situation in Afghanistan,” she said, her voice filled with emotion. “It is so hard to talk about it,” she added.

Unlike refugees from earlier times, today’s refugees are often able to speak with family and friends left behind on cell phones. Nazari tries to encourage them; there are opportunities for gifted Afghan women to find scholarships abroad, but the Taliban stands in the way. Under their regime, women need a “guardian” to apply for a passport or to leave the country.

“We all know it’s un-Islamic,” Nazari said of the Taliban’s policy prohibiting girls and women from attending college and secondary schools. She cited the Quranic injunction that knowledge and education is an obligation for the faithful.

Nazari spoke of adjusting to life in a new country among strangers. She explained that during her first month here, she didn’t leave the house where she was settled. She felt guilty having food and shelter, and the ability to continue her education, when she thought about her friends and family back home. But her family encouraged her. “You can be a voice for the women of Afghanistan,” they told her. Nazari is fulfilling their hopes. She recently earned an award from the Afghan American Writers Association.

President of Milwaukee Muslim Women’s Coalition, Janan Najeeb spoke about her organization’s involvement since the beginning of the Afghan crisis in 2021.

Janan Najeeb denounced the Taliban’s false narrative of Islamic tradition. “We know Islam is empowering,” she said. In her discussion with Atia Abawai, the two women agreed that the Taliban’s policy is all about power and control. Abawai quoted an old proverb, stating that when you educate a woman, you educate an entire family. She added that the Taliban, who are opposed to an educated society, seek to maintain their power over Afghanistan, placating men by giving them a sense of control over women in domestic life even though they have little control over the nation’s political life.

Najeeb described the pioneering work of the Milwaukee Muslim Women’s Coalition and their ability to aid the influx of Afghan refugees as they transferred from Fort McCoy to temporary accommodations in Milwaukee area motels. Programs for children remain a top priority, including singing, dancing, puzzles and story time as well as essential life skills for living in the U.S. Afghan and American societies have “different ideas about personal space,” she said. One of MMWC’s successes, the Buddy Program, pairs American-born kids with newly arrived Afghan children to learn from each other.

Many programs have been shifted to Hamilton High School with transportation in buses rented by Hanan Refugee Relief Group, including activities for the mothers of children. Hamilton is equipped to teach sewing and has a room with sewing machines. The Afghan women amazed the sewing instructor by producing “blouses, skirts and dresses in two hours without any patterns,” Najeeb said.

Many of the women suffer from depression after leaving behind family and friends. “What happens when you have two days to leave your country?” Najeeb asked. MMWC brought in a social worker who turned part of the sewing class into a support circle. MMWC assisted the social worker in crafting culturally appropriate programs and recruiting translators fluent in Pashto and Dari. She concluded by saying that more volunteers to help with the Afghan refugees are always welcome.

“Helping the helpers is our job,” said Ben York, describing the work of the Wisconsin Bureau of Refugee Programs. As refugee programs coordinator, he is responsible for placing federal and state funds in the hands of 30 partner organizations across the state. He added that Milwaukee receives 60-80 percent of newly arrived refugees in Wisconsin.

“The housing crisis in the U.S. provides an extra challenge,” York said, explaining why many Afghan refugees were housed in motels upon arrival. His agency relies on churches, community groups and organizations such as MMWC and the University School, which has a long history of in-kind donations and volunteer projects including English language tutoring.

Khatera Nazari pointed out the repression of women’s rights is a facet of the larger human rights crisis under Taliban rule. “I am a Hazara from Afghanistan, my people are facing genocide … only 2% of people have enough food to eat.” She added that she hopes to return to her homeland and “invest in the younger generations because my people need it.”

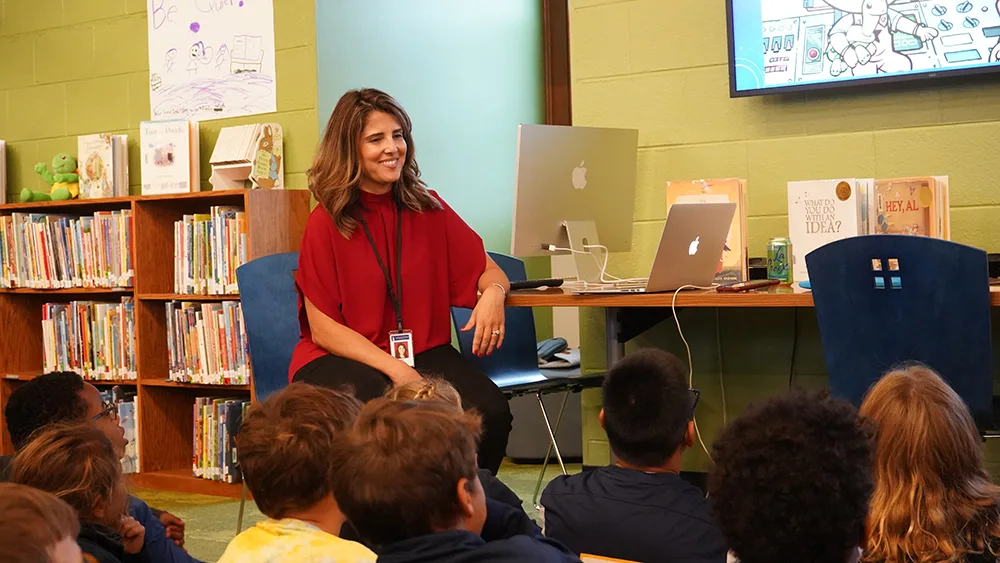

Photo courtesy of University School of Milwaukee

Atia Abawi’s visits University School of Milwaukee in October of 2022 and in January and April of 2023 for writing workshops, student assemblies, lunches with faculty and community panel discussions.

In an interview after the panel discussion, Abawi worried that “Afghanistan is no longer on the minds of most Americans, especially after 20 years of involvement there. But I am glad that most of the country is paying attention to what’s going on in Ukraine. Both of these stories are worth our attention. And I hope that we can find empathy for both populations and all populations that are suffering throughout the world.”