Stacy Conradt for Mental Floss

Wikimedia Commons

There’s more than one Independence Day in the U.S. On June 19, 1865, General Gordon Granger rode into Galveston, Texas, and announced enslaved people were now free. Since then, June 19 has been celebrated as Juneteenth across the nation. Here’s what you should know about the historic event and celebration.

1. ENSLAVED PEOPLE HAD ALREADY BEEN EMANCIPATED—THEY JUST DIDN’T KNOW IT.

The June 19 announcement came more than two and a half years after Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. So technically, from the Union’s perspective, the 250,000 enslaved people in Texas were already free—but none of them were aware of it, and no one was in a rush to inform them.

2. THERE ARE MANY THEORIES AS TO WHY THE EMANCIPATION PROCLAMATION WASN’T ENFORCED IN TEXAS.

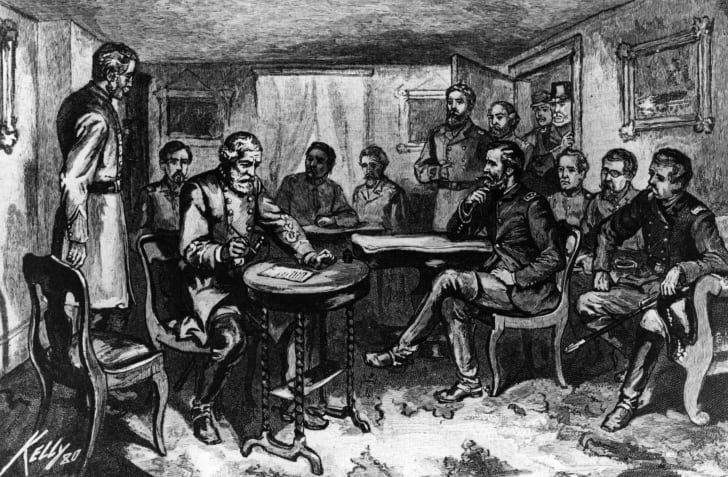

Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendering to Union General Ulysses S Grant at the close of the American Civil War, at the Appomattox Court House in Virginia on April 9, 1865. (HULTON ARCHIVE/GETTY IMAGES)

News traveled slowly back in those days—it took Confederate soldiers in western Texas more than two months to hear that Robert E. Lee had surrendered at Appomattox. Still, some have struggled to explain the 30-month gap between Lincoln’s proclamation and the enslaved people’s freedom, leading to speculation that some Texans suppressed the announcement. Other theories include that the original messenger was murdered to prevent the information from being relayed or that the federal government purposely delayed the announcement to Texas to get one more cotton harvest out of the enslaved workers. But the real reason is probably that Lincoln’s proclamation simply wasn’t enforceable in the rebel states before the end of the war.

3. THE ANNOUNCEMENT ACTUALLY URGED FREEDMEN AND FREEDWOMEN TO STAY WITH THEIR FORMER OWNERS.

General Order No. 3, as read by General Granger, said:

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.”

4. WHAT FOLLOWED WAS KNOWN AS “THE SCATTER.”

Most freedpeople weren’t terribly interested in staying with the people who had enslaved them, even if pay was involved. In fact, some were leaving before Granger had finished making the announcement. What followed became known as “the scatter,,” when droves of former enslaved people left the state to find family members or more welcoming accommodations in northern regions.

5. NOT ALL ENSLAVED PEOPLE WERE FREED INSTANTLY.

Texas is a large state, and General Granger’s order (and the troops needed to enforce it) were slow to spread. According to historian James Smallwood, many enslavers deliberately suppressed the information until after the harvest, and some beyond that. In July 1867 there were two separate reports of enslaved people being freed, and one report of a Texas horse thief named Alex Simpson whose enslaved people were only freed after his hanging in 1868.

6. FREEDOM CREATED OTHER PROBLEMS.

Despite the announcement, Texas slave owners weren’t too eager to part with what they felt was their property. When freedpeople tried to leave, many of them were beaten, lynched, or murdered. “They would catch [freed slaves] swimming across [the] Sabine River and shoot them,” a former enslaved person named Susan Merritt recalled.

7. THERE WERE LIMITED OPTIONS FOR CELEBRATING.

A monument in Houston’s Emancipation Park. (Flickr)

When freedpeople tried to celebrate the first anniversary of the announcement a year later, they were faced with a problem: Segregation laws were expanding rapidly, and there were no public places or parks they were permitted to use. So, in the 1870s, former enslaved people pooled together $800 and purchased 10 acres of land, which they deemed “Emancipation Park.” It was the only public park and swimming pool in the Houston area that was open to African Americans until the 1950s.

8. JUNETEENTH CELEBRATIONS WANED FOR SEVERAL DECADES.

It wasn’t because people no longer wanted to celebrate freedom—but, as Slate so eloquently put it, “it’s difficult to celebrate freedom when your life is defined by oppression on all sides.” Juneteenth celebrations waned during the era of Jim Crow laws until the civil rights movement of the 1960s, when the Poor People’s March planned by Martin Luther King Jr. was purposely scheduled to coincide with the date. The march brought Juneteenth back to the forefront, and when march participants took the celebrations back to their home states, the holiday was reborn.

9. TEXAS WAS THE FIRST STATE TO DECLARE JUNETEENTH A STATE HOLIDAY.

Texas deemed the holiday worthy of statewide recognition in 1980, becoming the first state to do so.

10. JUNETEETH IS STILL NOT A FEDERAL HOLIDAY.

Though most states now officially recognize Juneteenth, it’s still not a national holiday. As a senator, Barack Obama co-sponsored legislation to make Juneteenth a national holiday, though it didn’t pass then or while he was president. One supporter of the idea is 93-year-old Opal Lee—in 2016, when she was 90, Lee began walking from state to state to draw attention to the cause.

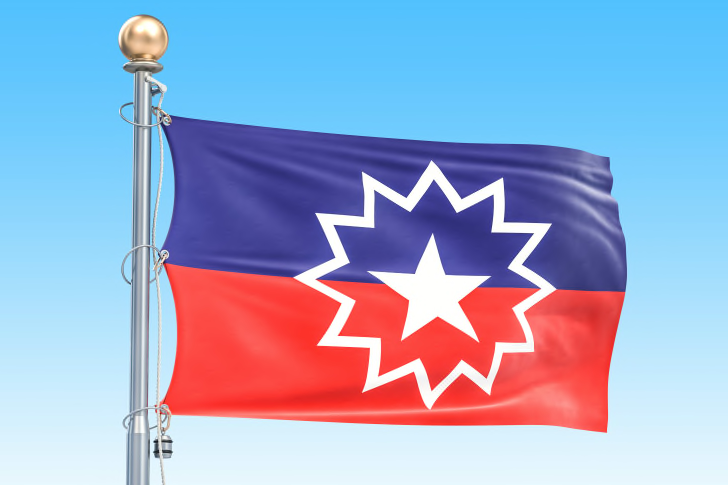

11. THE JUNETEENTH FLAG IS FULL OF SYMBOLISM.

Juneteenth flag designer L.J. Graf packed lots of meaning into her design. The colors red, white, and blue echo the American flag to symbolize that the enslaved people and their descendants were Americans. The star in the middle pays homage to Texas, while the bursting “new star” on the “horizon” of the red and blue fields represents a new freedom and a new people.

12. JUNETEENTH TRADITIONS VARY ACROSS THE U.S.

As the tradition of Juneteenth spread across the U.S., different localities put different spins on celebrations. In southern states, the holiday is traditionally celebrated with oral histories and readings, “red soda water” or strawberry soda, and barbecues. Some states serve up Marcus Garvey salad with red, green, and black beans, in honor of the black nationalist. Rodeos have become part of the tradition in the southwest, while contests, concerts, and parades are a common theme across the country.