During a Zoom panel sponsored by Ma’ruf Center, Sean Wilson introduces himself as the statewide organizer of the ACLU’s campaign for Smart Justice. He goes on to say, “My organizing started when I was held captive in the Wisconsin Department of Corrections[and] has continued . . . here in the State of Wisconsin and the City of Milwaukee as we continue to fight these oppressive systems that prevent us from living our best lives.”

Wilson is articulate, centered, clean-cut, and disciplined, an impressive and commanding presence on the Zoom panel, which was presented as a Call to Action in response to the anti-police brutality movement that sprang up in the wake of the murder of George Floyd.

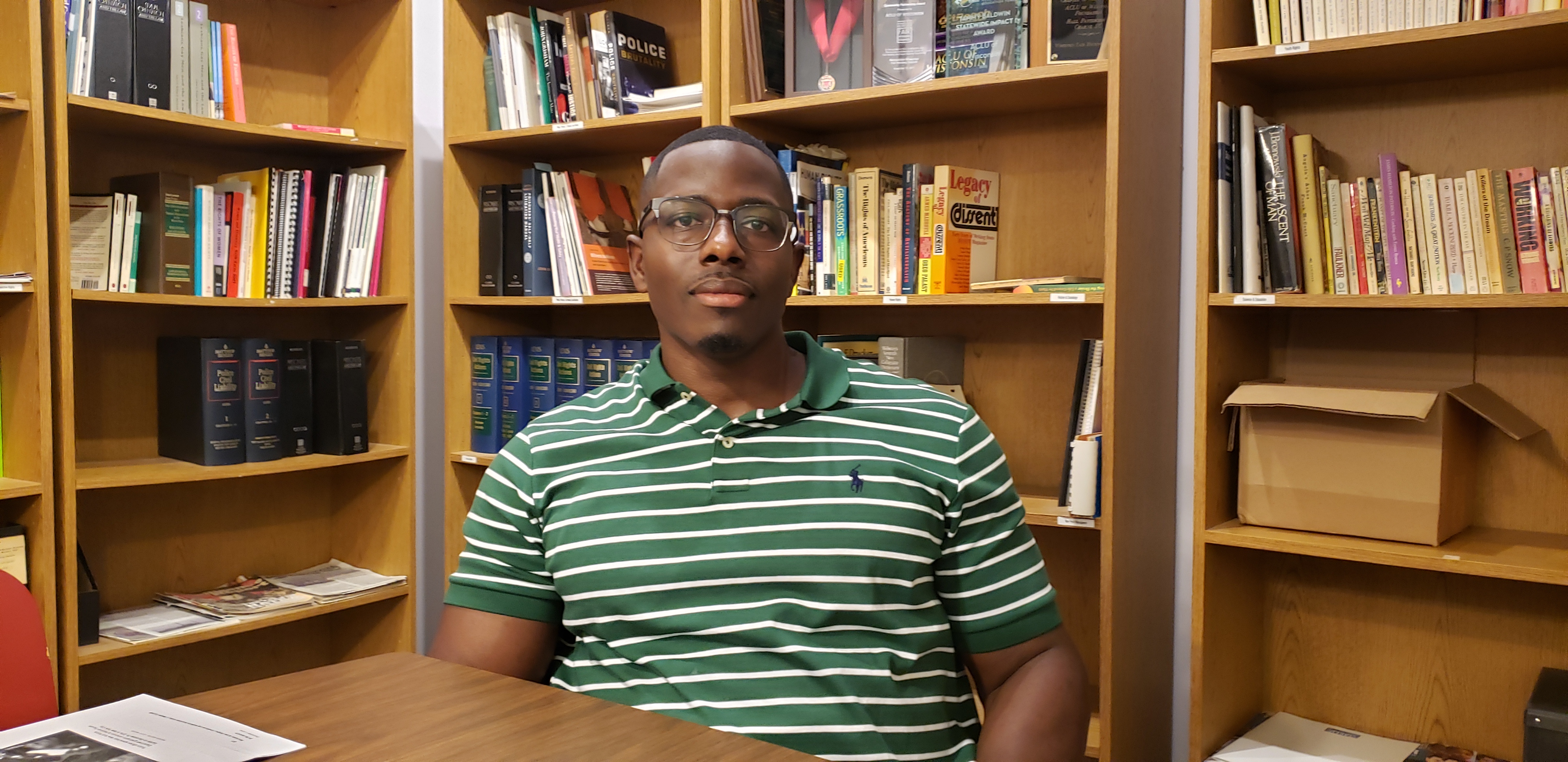

Wilson is equally impressive when I meet him a week later for an interview at ACLU’s Milwaukee headquarters, but in addition he’s also friendly and cordial, offering water as we sit down at the conference table.

A registered lobbyist with the State of Wisconsin, Wilson spends a lot of time in Madison these days, in addition to doing Smart Justice trainings for churches and organizations. According to ACLU’s web site, Smart Justice is “an unprecedented, multi-year effort to reduce Wisconsin’s jail and prison populations by 50 percent and to eliminate racial disparities in the criminal justice system.” The campaign collaborates with multiple community partners that have included the Wisconsin Education Network, Wisdom, the Badger Institute, and Americans for Prosperity.

And from his comments on the Ma’ruf panel, it seemed that Wilson, who is 38, had the life experience to bring to his work as an organizer. I assumed his comment referred to a stretch of jail or prison time due to a long-ago youthful indiscretion – the kind of indiscretion that weighs much more heavily on the black community than on the white, but surely no more than, say, 18 months.

As Wilson describes it, “At the age of 17, I, along with a few friends, made a poor decision and committed a robbery. We robbed a person. Two adults and me and my friend, the only teen-agers. . . . Unfortunately, the courts held us to the same standards that they held the adults to. I was automatically waived into adult court.”

On the recording of my conversation with Wilson, you can hear me say, “What!” when he tells me that he served 17 years. Sean Wilson doesn’t just talk about the mass imprisonment of black men that began in the 1970s and resulted in the incarceration rate in the United States increasing by more than 400%. He lived what author Michelle Alexander has called “the new Jim Crow.”

Even though more people than ever were being jailed, for fearful white Americans, it was not enough. People were coming out of prison after serving a fraction of their time and then re-offending. In the 1990s, a “truth in sentencing” trend began, directly impacting Sean Wilson’s life. According to Wisconsin Lawyer, prior to Wisconsin Act 283, “The offender rarely served the prison term actually imposed. An offender served six months or one-quarter of the court-imposed sentence, whichever was greater, before becoming eligible for parole.”

Truth in Sentencing became the law in Wisconsin on Dec. 31, 1999. “I was one of the first bunch of folks sentenced under Truth in Sentencing,” Wilson said. But the sentence he received was probably inherently unfair. “I was over-sentenced,” Wilson said. Milwaukee County Circuit Court Judge Bonnie Gordon, who left the bench in 2014, “threw the book at me.”

Wilson thinks that had he been “a white kid, the balance of the scales would have been a little different. If you look at my record . . . I never had any priors. I had academic scholarships as well as athletic scholarships. I was a junior in high school” who had attended both grade school and high school at Franklin public schools, where he was bussed from his home at 13th and Burleigh.

After his sentencing, the 17-year-old Wilson was remanded to Green Bay Correctional institution, one of four maximum-security prisons in Wisconsin, which he says was known as “gladiator school” because “there was a lot of fights there. And the reason there was a lot of fights there was because you had a facility full of kids who were 17, 18 years old.”

That is when his life began to change into what it is today, said Wilson. “I knew that I had to figure out how I got there. And I also knew I needed to begin to heal and understand my . . . situation. I knew that I needed to better myself so that I can re-enter society as a better human being, that I can contribute to its forward progress.”

Today, one focus of that forward progress – and of Wilson’s work with the Smart Justice campaign — is putting an end to the practice of technical revocations. “Basically, it’s sending people back to prison for violating a rule of supervision,” Wilson said, not for committing a new crime, but for being late to an appointment with a parole officer or some similar infraction. “It’s very arbitrary,” Wilson says. “We’re sending over 3,000 people back to prison each year, spending $197 million just to cage these individuals.”

Molly Collins, Advocacy Director for ACLU of Wisconsin, and one of the people who interviewed Wilson for his current position, said that, “Sean has changed the way the ACLU organizes around criminal justice reform,” because of his ability in “building and deepening relationships with many people and communities who are impacted by the criminal legal system. He also has committed himself to changing these systems by working in the State Capitol as a lobbyist to educate the legislature on these issues and has met with leaders in various parts of the state government to share his ideas and experience with them.”

Ironically, without Wilson’s life experience, he might be much less effective. “It often seems novel to these elected and appointed officials to ask someone who has been impacted by the criminal legal system how it works,” Collins wrote in an email, “but Sean immediately shows them the value of listening to a person with direct experience. These meetings usually end with the officials having taken pages of notes of Sean’s well-developed and important ideas.”

That is the remarkable thing about Sean Wilson. After spending half his life in prison, and with only 4 years in the free world, he is already making a significant contribution, in large part because his development began while he was incarcerated.

“Most of the folks who were incarcerated with me, there’s three things they’re gonna say about me,” Wilson said. ‘“He works out a lot. He reads a lot. And he’s always challenging the injustices of the officers and the administration within the prison.’”

In prison, Wilson read Freud, Noam Chomsky, Malcom X. In fact, Wilson read so much, that he was once written up for having too many books. Wilson had 40 books in his cell. The DOC had established a limit of 25. “The charge that they gave me for having over 25 books was ‘possession of contraband.’ They said the 15 additional books was contraband,” Wilson said.

But he said he was also well read on “the administrative policies of the institution as well as the 303.” Chapter 303 of the Department of Corrections Administrative Code relates to inmate discipline. “The narrative that Corrections gives the public is, ‘We’re rehabilitating these individuals,’ and that is not the case. You had officers who were just the worst. When I recognized that there was a particular officer that had a tendency to harass guys and trash their cell, I began to say, ‘Hey, we don’t have to accept this. We can file a complaint. This is not allowed in their work rules.’”

And so Wilson’s career as an organizer was born.

Central to Wilson’s development, both intellectually and morally, was becoming a Muslim. While in the custody of the Wisconsin DOC, Wilson said, “I began to meet all types of individuals who were serving significant amounts of time, individuals who had a letter – a life sentence. A lot of these guys were very intelligent, very learned individuals. They began to give me books . . . and ultimately gave me the Qur’an . . . I took my shahada and I became a Muslim. I’ve been a Muslim now for about 16, 17 years.”

Today, Wilson, despite having served hard time, is a man who lives without resentment. “The Prophet Muhammad, Peace Be Upon Him, said that ‘whatever hits you, wasn’t meant to miss you. And whatever misses you, wasn’t meant to hit you.’ In Allah does the believer put their trust. Though I went through what I went through, this was God’s will.”

Nevertheless, Wilson clearly understands the political implications of what happened to him, and the impact on others who are still in the system. And while he used his prison sentence as an opportunity to become the person he is today, that long sentence had its own tragic consequences. Wilson’s beloved grandmother, Vera Green, died two weeks before his release. “My grandmother, who raised me from birth, used to come and visit me every weekend, and I used to always tell her, when I come home, I’mma make you proud, and she was like, ‘I know baby. I know. Just come home.’”

Wilson also credits a strong family, including his mother, sisters, brothers, aunts, uncles, and cousins for the life he was able to build upon his release. “I had the support of my family awaiting me. . . . I came home and began to do work in the community, mentoring, starting my own personal training business.” Prior to the ACLU, “I was working with Youth Justice Milwaukee, mentoring young folks,” Wilson said.

Sharlen Moore, a co- founder of Youth Justice Milwaukee, met Wilson shortly after his release from prison, when she said, “We ended up on the same kickball team.” Like most people, upon learning his history, she said “Oh, my goodness! You have such a powerful story.”

Wilson, said Moore, is “such an amazing advocate. He comes from a place of passion.” He has had “the experience of injustice . . . but instead of just brushing it off, he said, ‘It is my responsibility to share my experience with the world, and it is my role to change things.’”

As Wilson himself put it during the Ma’ruf panel, “We have to make sure we’re giving guidance to the younger generation. We don’t have to tell them what to do, we just have to show them how to do it in a more strategic way. I understand youthful passion. I understand what that can get us. But we have a responsibility to show them the path so they can walk into it and lead it according to their own vision.”

These values also extend to Sean Wilson’s personal life. “I got married a year after I came home,” he said. His wife Latasha is a teacher at the Lola Rowe North campus of Milwaukee College Prep, a K-8 public charter school. The couple met in April 2017 at the gym, where Latasha Wilson said she was “using the machines wrong, and at the time he was a personal trainer so he offered some assistance.”

The two began dating and Sean “was always finding stuff for us to do. Let’s go to the lake, let’s go get ice cream. I was in a place in my life where I wasn’t emotionally available, but he made me feel like he really cared.”

Latasha Wilson grew up in the Pentecostal Apostolic church, so adapting to Sean’s Muslim faith, “wasn’t much of a transition” she said. “I grew up in that way already, being a modest woman, going to church all the time. In the beginning, we had a lot of conversations about how this was going to work. He was very confident. He said Christians and Muslims get married all the time.” Now the couple “study together about how the religions are interconnected.” Latasha Wilson said the couple is “not letting that be an issue in our marriage. We respect each other. We respect each other’s beliefs. It’s about knowing where to let somebody be their own person.”

The couple have a one-year-old son and are raising Latasha’s nephew, age 5. “My nephew is not my biological child,” Latasha said, but Sean’s parenting him “speaks to [his] character of being whatever people need him to be and walking into that role with grace. My nephew calls him dad. He saw the need of my nephew and put that first.”

Sean, she said, “is a very, very devoted and loving dad, always wanting to be a part” of the children’s lives. The couple, who are expecting a baby daughter, do 80 percent of the childcare together, Latasha Wilson said.

Sean Wilson was deprived of 17 years of his young life by the justice system, so perhaps it’s not surprising that he is so determined to get the most and give the most in the life he has now. But it is surprising that he was able to turn 17 years in prison into a skill set that he is now using to reshape, not just his world, but that of others. The man who served a sentence that, on its very face, was unjust, works to make sure others are given the chance to “live their best lives.”