Photo©:

Jeff Miller, University of Wisconsin-Madison’s University Communications

A year ago this week the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed the first case of COVID-19 in the United States. Wisconsin’s first case was confirmed on Feb. 5, 2020. Since then, Wisconsin has seen more than half a million cases of coronavirus and almost 5,500 deaths, according to the Wisconsin Department of Health Services.

A week ago today, Wisconsin’s first documented case of a variant of the virus that is believed to spread faster than other common versions was identified by the Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene, raising concerns that COVID-19 will soon become more widespread in Wisconsin.

What have we learned about its spread and how to prevent it? Experts, as well as individuals who have suffered with coronavirus, shared their knowledge and experience with the Wisconsin Muslim Journal on this grim anniversary.

Beyond the numbers

Dr. Thomas Friedrich, a professor of virology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s School of Veterinary Medicine, leads a team of 14 researchers in the Friedrich Laboratory that is part of a nationwide network of labs organized by the CDC that helps track how SARS-CoV-2 is spreading throughout the country.

In collaboration “with Dr. David O’Conner’s Laboratory in UW-Madison’s School of Medicine and Public Health, and many others, we are using genetic signatures of different SARS-CoV-2 viruses to track how the virus is spreading to and within Wisconsin,” he told WMJ.

“Our results, together with those of the broader network, suggest that new SARS-CoV-2 strain, first detected in the United Kingdom, which we are calling B.1.1.7, is present in many places in the country, including in Wisconsin. Right now this new strain has only been detected one time in Wisconsin, but I think we have to assume that it is causing more infections here.”

While this new variant seems rare now, Friedrich said he and his colleagues are concerned “that B.1.1.7 will continue to cause more infections, and will become more common over the next couple months. There is good evidence from the U.K. that this strain is more contagious than previous SARS-CoV-2 strains — about 1.5 times more.

“It’s important to say this new strain is no more likely to cause severe disease than prior strains, and we expect it will still be susceptible to vaccines,” he said. “However, because it is more contagious, it will be more difficult to control its spread.

“And more cases overall will mean more severe cases, likely more deaths and more strain on our health systems in Wisconsin. In the U.K., the new strain has become the most common strain over a span of about two-three months. The number of new cases was growing so fast that the U.K. went back into a strict lockdown to control it.

“I hope that does not become necessary here, but we should definitely be prepared for this strain to become more common and for new infections to increase as it does,” he said. “We will need to be prepared to take more stringent measures to control it.”

Are we doing enough to control it?

“Unfortunately, we are not doing enough,” Friedrich said. “SARS-CoV-2 is still spreading and causing disease in our communities, and we will likely see things get worse as the B.1.1.7 strain or others like it become more common.

“The good news is that the same measures that protect us against other strains will protect us against new ones — masking, distancing, hand-washing and avoiding gatherings with people outside our households. I know we are all tired of sticking with these things, but they will become even more important if the virus becomes more contagious.

“At the same time, we are lucky to have safe and effective vaccines available,” he added. “We need to be doing everything we can to vaccinate as many people as possible. This will protect individuals and also help ease the burden on the healthcare system.

“We expect viruses like SARS-CoV-2 to evolve. Each time the virus infects a new person, it can make one-two random mutations. This is kind of like pulling a slot machine handle — most of the time, the random change will not be helpful to the virus, but the more chances we give it, the greater the likelihood that eventually a random change will make it easier for the virus to infect people. So, controlling the spread also limits the virus’s ability to adapt.”

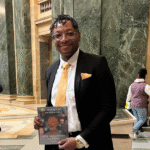

(From left to right) Juman, Nour and Wafaa Elqaq, Sahar Bitar, and Nadeen, Layan and Ibrahim Elqaq in Jaffa last summer.

“You don’t want this virus!”

For one Franklin family, November “was miserable.” On Nov. 1, Sahar Bitar’s daughter Juman Elqaq, 17, was sent home from school because she had been in contact with a classmate who tested positive for COVID-19. In a few days, Juman started having a runny nose.

“It was like a typical cold. We thought nothing of it,” but about week later Bitar’s husband, Wafa Elqaq started coughing. He tested positive for coronavirus so he stayed home from work, but his cough kept getting worse. His doctor gave him a device that measured his oxygen level. His fever went up to 103 degrees Fahrenheit and his oxygen level kept dropping. He developed a hard cough.

Elqaq was admitted to Froedtert Hospital Nov. 7. No one could visit him, so his daughter Nour, 25, who is a nurse, asked her father to call when the doctor came to his room so she could get updates on his condition.

After five days, Elqaq was sent home with a portable oxygen tank. He needed oxygen to walk up the stairs, Bitar said.

Meanwhile, the virus circulated through the family.

“Everyone experienced it in a different way,” said Bitar. Juman had a mild case, but afterwards broke out in hives. Layan, 23, and Nadeen, 21, also had mild cases, but couldn’t taste or smell anything. Nour had a body ache and felt very tired. She had just started a new job and had to be off two weeks. Even Nour’s fiancé, who arrived from Jordan on Oct. 25, caught the virus.

Bitar and Elqaq worried about their 15-year-old son Ibrahim, who has asthma. “I asked him to please stay in the basement and stay away from us all,” Bitar said. He never had any symptoms, but ended up testing positive.

“I had a slight fever, a headache and a stomach ache,” she continued. “I lost my senses of smell and taste. That was in November and they are only beginning to come back now. God gave us something wonderful, but we don’t appreciate it until we lose it.”

It was mid-December before everyone in the family recovered. “But it has affected us,” Bitar said. “I still feel tired.

“Believe me, everyone has to take this seriously,” she added. “My friend lost her brother and he was young.”

18 days in the hospital

Abdelhafeth Hamed of Milwaukee, known to all as Abu Majid, and his family were driving home from Kentucky on June 23. They reached 23rd and College, and stopped for gas. Hamed stepped out to fill up the car.

“Suddenly I was shaking. I told my wife I think I have a virus,” he said. When he got home, he had a fever and chills. “That was Sunday night. The next day I also had a headache and a cough.”

On Wednesday, he went to his doctor and was tested for COVID-19. The results came back positive. He quarantined at home, but kept feeling worse, being extremely tired and short of breath.

By the following Monday, he decided to go to the hospital and called for an ambulance. “By the time I got there, I was out,” he said.

His memories from the beginning of his 18-day hospital stay are hazy, he said. He remembers a doctor saying, “Mr. Hamed, we are losing you every minute. I’m afraid we are going to have to put you on a ventilator.”

Amal and Abdelhafeth Hamed of Milwaukee

Hamed asked if there was an alternative. The doctor agreed to have him lie on his stomach, take in oxygen through his nose and out his mouth, and see if he would be able to breathe on his own, he said.

“I remember when she said, ‘Congratulations, you made it,’ he said. “I felt like I died and came back.”

In addition to having coronavirus, Hamed developed pneumonia, he said. “I was so tired. I had a problem feeding myself.” The first 12 – 13 days were horrible.”

“When I took breaths, it felt like the air would not pass my throat,” he said.

And after Hamed went home, he still needed oxygen. “It took seven to 10 days before I could walk a few feet,” he said.

Hamed wants others to know “this is very serious. People should think a million times before they take a risk of getting it.”

His wife and two daughters also had the virus but did not have to be hospitalized.

How to stay safe

Through the experience of the pandemic in the past year, we have learned we should continue to be cautious, especially because the virus may become more aggressive, Milwaukee pulmonologist Raed Hamed, M.D., told Roya News in Amman, Jordan.

Hamed is an executive board member of Jordanian American Physicians, which produced an informational video in Arabic to encourage Jordanians to take the COVID-19 vaccine.

In a broadcast last week, Hamed told the independent news station we should continue safe practices such as physical distancing, wearing masks, minimizing visits beyond one’s household and to take the vaccine when given the opportunity.