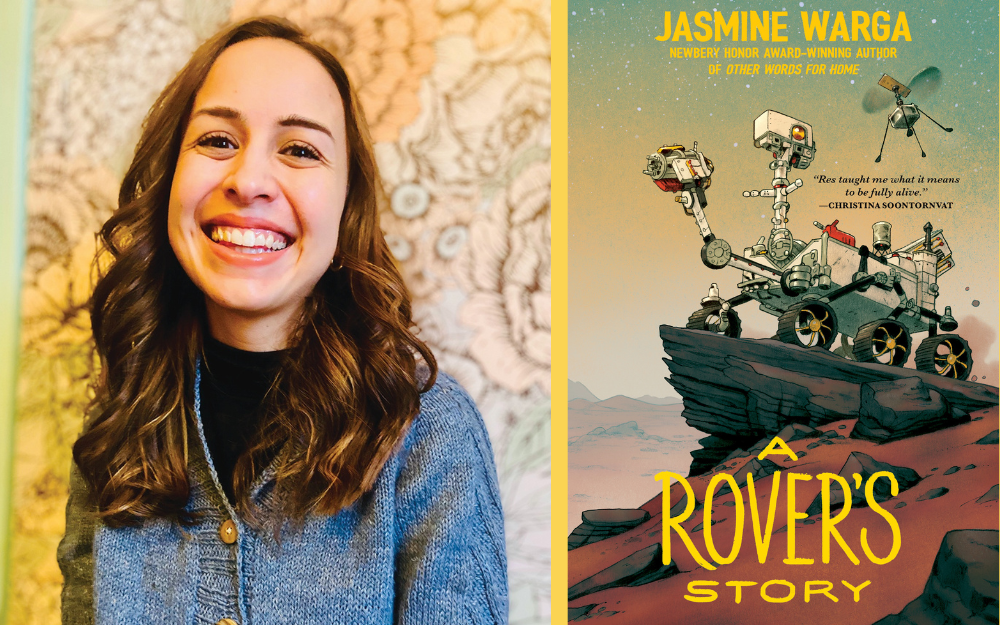

Author Jasmine Warga with her latest novel “A Rover’s Story” about belonging and home, the center of every immigrant story.

“From a very early age, I thought a lot about what ‘home’ means,” Newbery Honor Book author Jasmine Warga said an interview Monday with the Wisconsin Muslim Journal. As the daughter of a son of Palestinian refugees, “so much of our family story and history has been talking about home—leaving home, making a new home and honoring the home of our past,” she said.

Growing up in a small town near Cincinnati, Ohio, people always asked her, “Where are you from?” She realized she looked different from her peers and was the only Muslim in her elementary school class. Yet when she visited family in Jordan, she was “the American.”

“As a kid, I wanted to fit in,” she recalled. “I spent a lot of time thinking about belonging. What does it mean to belong?”

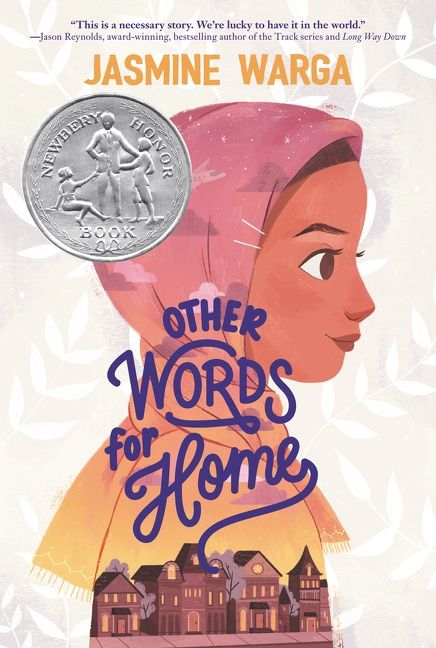

Warga’s middle-grade novel Other Words for Home, a 2020 Newbery Honor Book, explores those questions from the perspective of Jude, a 12-year-old Syrian girl who, with her mother, fled the violence of war and immigrated to Cincinnati, where she confronts the challenges of being Muslim and Arab in the United States.

In her new middle-grade novel, A Rover’s Story, to be published Oct. 4, the protagonist is a Mars rover named Resilience. “The main character is a robot but it is still a story about belonging,” Warga said. “What does it mean to leave home, everything you’ve ever known? That’s the crux of every immigrant story. And it’s the engine that fuels my writing.”

Warga teaches in the MFA program at Vermont College of Fine Arts. Originally from Cincinnati, she lives in the Chicago-area with her family.

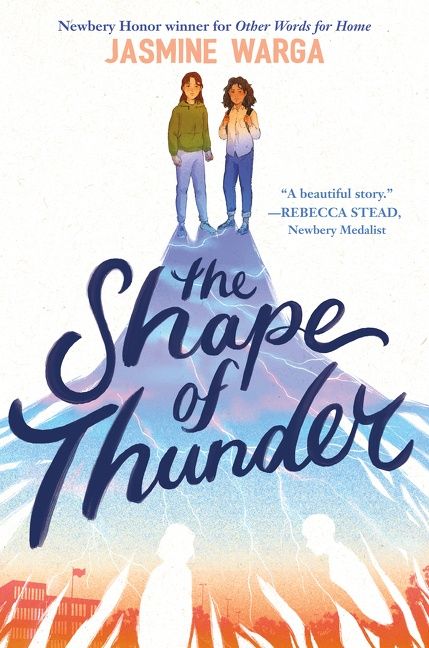

She is the author of the children’s books Other Words for Home, a Newbery Honor Book and a Walter Honor Book for Younger Readers, and The Shape of Thunder. Her teen books, Here We Are Now and My Heart and Other Black Holes, have been translated into over 25 languages.

The Milwaukee Muslim Women’s Coalition and the Boswell Book Company are co-sponsoring Jasmine Warga in Conversation with Amanda Zieba at the Greenfield Public Library, 5310 W. Layton Ave., Wednesday, Oct. 5, at 6:30 p.m.

“We are looking forward to the upcoming visit from award-winning author Jasmine Warga—such a talented, impactful up-and-coming children’s and teen’s author,” Greenfield Public Library Director Sheila O’Brien wrote in email to WMJ. “We expect a lively and enthusiastic turnout for the author visit, especially since this will be our first one in the post-pandemic season.”

The Greenfield Public Library has in its mission to present for patrons of all ages a broad and diverse cross section of viewpoints, opinions, traditions, values, lifestyles, cultural backgrounds, and demographic groups on important issues of the day, O’Brien noted.

Registration to the Jasmine Warga Author Talk is required and opened now through this link.

Chatting with Jasmine Warga

In an interview with WMJ Monday, author Jasmine Warga talked openly about her writing and being a Palestinian American has given her a valuable perspective. Here are the highlights.

“The Shape of Thunder” is a touching story about friendship, grief and the ways we cope with emotions.

I can see as a Palestinian American, you would be able to empathize and understand the plight of Syrian refugees, like the protagonist in Other Words for Home, but in A Rover’s Story, the main character is a robot. Was it difficult to write from that perspective?

I think all robot stories are really stories about what does it mean to be human. My robot worries a lot about having human feelings, worried that makes him a bad robot who doesn’t fit in with the other robots. This idea of being an outsider, of having things that make you different and then growing throughout the story to see that is maybe what also makes him special.

When I do school visits with kids, I’m always talking about the way to find your voice as a writer is to think about what are the things that matter to you. What are the things that you wonder a lot about? And for me those are home and family and belonging. Those were the big questions of my own adolescence and are still the big questions of my adult life.

What inspired you to write about a robot?

I was actually inspired by my own daughter who wanted to watch the launch of the newest NASA rover. We watched it together in July 2020. When the rocket carrying the rover was going into the air, my older daughter, who is 6, was jumping and clapping. But my younger one, a 5-year-old, looked really concerned.

So, I asked her, “What’s wrong sweetheart? It was a successful launch.”

And she says, “Yeah, but Mama, do you think the robot is scared?” I thought to myself, what a beautiful story idea. Is this robot scared to leave home?

And I started to think like, what a beautiful story idea. Like is the robot afraid? What does it mean to have human feelings? And then I started thinking about this idea of is, is the robot scared to leave home?

It sounds like the stories in Other Words for Home and A Rover’s Story are very similar.

Yes, I’m writing about all of the same things in this book that I wrote about in Other Words for Home, just from a different angle. In this story, one of the main scientists who works on the robot is an Arab American woman with a daughter. Most of the book is from the robot’s point of view but there are letters from her daughter in the book, so there are a few cultural nods here. The daughter processes her own preteen emotions and feelings about her mom being so busy in the lab with the rover.

That’s exciting to me because if I had pulled this book off the shelf when I was in fifth grade, I would have been so excited not only to find this fun space adventure book but also to see a few Arabic words. That would have been very surprising and fun.

Are you writing for Arab American or Muslim American children and youth?

When I’m writing, I’m always writing for young me. That’s the only child whose interior workings I have known. In that way, I am always thinking about Arab American and Muslim kids who haven’t gotten to see themselves in a book in a positive light. That’s so important to me.

First grader, Jasmine Warga at an event called “Author’s Night”

But I was also growing up in a small Ohio town where everyone around me was Christian and celebrating Christmas. My mom had grown up with these holidays. So, we got a tree and Santa Claus came to our house. And on the Eid, we’d get cookies and money. Growing up, we celebrated all the holidays.

From an early age, I understood the nuances of all the hyphenated parts of my identity, that my family is Palestinian but lives in Jordan now. Then my dad moved to America and I’m half this and half that. So, I have always been thinking about identity and belonging.

However, some of the most moving letters I have received from readers are from kids who have never before encountered a Muslim or a Muslim character in a book. The book shifted their perspective and understanding. I love writing for young people for that reason—because the books you read when you are young live in your fiber and have the ability to expand your heart in a way that’s harder to do as we get older.

Tell us a bit about your family.

My father is Muslim. He was born in Jordan, the son of Palestinian refugees. My mother converted to Islam when I was a child. But I’ve always thought of myself as coming from a mixed-faith family. My dad instilled in us the idea that we came from a Muslim family. My great-grandfather was a caretaker at Al Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem. A big part of being an immigrant is wanting your kids to know where you came from.

Jasmine Warga with her Palestinian Grandmother

We were the only Muslim family at my elementary school. In my memory, I was the only child of an immigrant. I looked different from my peers. I was always asked where I came from. In some ways, I feel like my connection to being Arab also came from the way other people reacted to me. I went through a phase in middle school where all I wanted was to fit in. I wanted to like pass under some radar, not having people call out that I was clearly different from the rest of my peers. Then, I’d go to the Middle East to visit and I felt very American.

What inspired you to write about a Syrian refugee in Other Words for Home?

Our closest family friends were Syrian American. That book was directly inspired by sort of watching members of their family come over to live with them because of the conflict in Syria. I began wondering what it would have been like for me in middle school if my cousins in Jordan came to live with us. The story would be about an American girl whose cousin comes to live with her. Then, as books often do when you are writing, the perspective changed and I told the story from Jude’s (the refugee’s) perspective.

How did 9/11 impact your childhood?

It was obviously very informative for the way I felt about myself. I was in 9, in eighth grade. Before 9/11, I felt invisible in books. I never saw characters who came from the same background as I did, who practiced the religion my family practiced at home, who ate the same foods or any of those things. Then, after 9/11, suddenly everyone was talking about the region in the world where my family came from, about my religion, but they were doing so in a really negative, pejorative way.

“Other Words for Home” explores questions from the perspective of Jude, a 12-year-old Syrian girl who fled the violence of war and immigrated to Cincinnati.

Just when I started to feel I could be Arab and Muslim and American, the media I was consuming told me there was something oppositional between these different parts of my identity. In writing Other Words for Home, I was saying no to those messages. There’s a lot of beauty and power in a hyphenated identity. You can be Arab and American, Muslim and American. That is something I didn’t understand when I was 12 and 13. And I definitely didn’t see any stories that supported me. The media I consumed made me feel bad about these parts of my identity.

How did you resolve this identity crisis you felt?

When I got to college, I met other Arab Americans and other Muslim Americans. Through conversations with them, I began to feel this thing that had made me feel so different also gave me a special perspective.

I still feel I am always explaining my identity, parsing out these different parts of myself. But what I discovered is that I’m really proud of being Palestinian American. I am proud those stories of my ancestors live on in me and I’m able to tell them. I’m also really proud to be from Cincinnati, Ohio. That’s the city that raised me. Both of those identities exist in the way I tell stories. The hyphen doesn’t have to be a divider; it can be a bridge.